When we first invested in Redbox, we knew that the DVD rental business was going away, being replaced by streaming. We placed a bet on a business that we knew would peak in seven to 10 years and that’s exactly what happened. It was terrifying and exciting all the same to experience incredible growth but know for certain that it was going to end.

Peter Rowan Executive Director, Innovation & Entrepreneurship Center

Peter Rowan joined Albers in September 2021 as the Executive Director of the Innovation & Entrepreneurship Center (IEC) and the Lawrence K. Johnson Endowed Chair in Entrepreneurship. Rowan was previously Executive Director of the Pacific Asian Center for Entrepreneurship and a senior lecturer at the Shidler College of Business at the University of Hawaii – Manoa. Before venturing into higher education, he served as Corporate Vice President, New Ventures at Coinstar, from 2001 to 2010. Rowan continues to be active in the entrepreneurial community as an advisor, mentor, and investor. In this piece, he shares his thoughts on entrepreneurship, the IEC, and shifting careers.

You’ve worn both academic and corporate hats in your career. Was this by design? How have both influenced your thinking and life’s philosophy, if at all?

I started teaching as an adjunct 15 years ago, while I was running the new venture growth strategy for Coinstar, and realized that I enjoyed that one quarter more than any other time of the year. I found that being challenged by students to justify the strategic decisions we made in growing our businesses made me a better thinker. Often, in growing companies too much time is shifted to administrative matters that are not really core to the business and no one is quicker to see through that nonsense than students.

Roughly eight years ago, I began a long, challenging process of shifting from a corporate entrepreneurship career into an academic one, including pursuing a PhD. I thought it would be easy to make that shift but I badly misunderstood the nature of the academic work, particularly the scholarship and service. I thought loving to teach and sharing my experiences as an entrepreneur would be enough. That was extraordinarily naive.

That said, in entrepreneurship we talk about the importance of being able to adapt and pivot to obstacles and harsh feedback. I think I have been able to do that repeatedly. Many people told me this was a bad idea -- to change careers. But then again, as an entrepreneur, most of the time that’s what you hear --that what you are doing is not going to work. You just have to absorb what is useful and keep going.

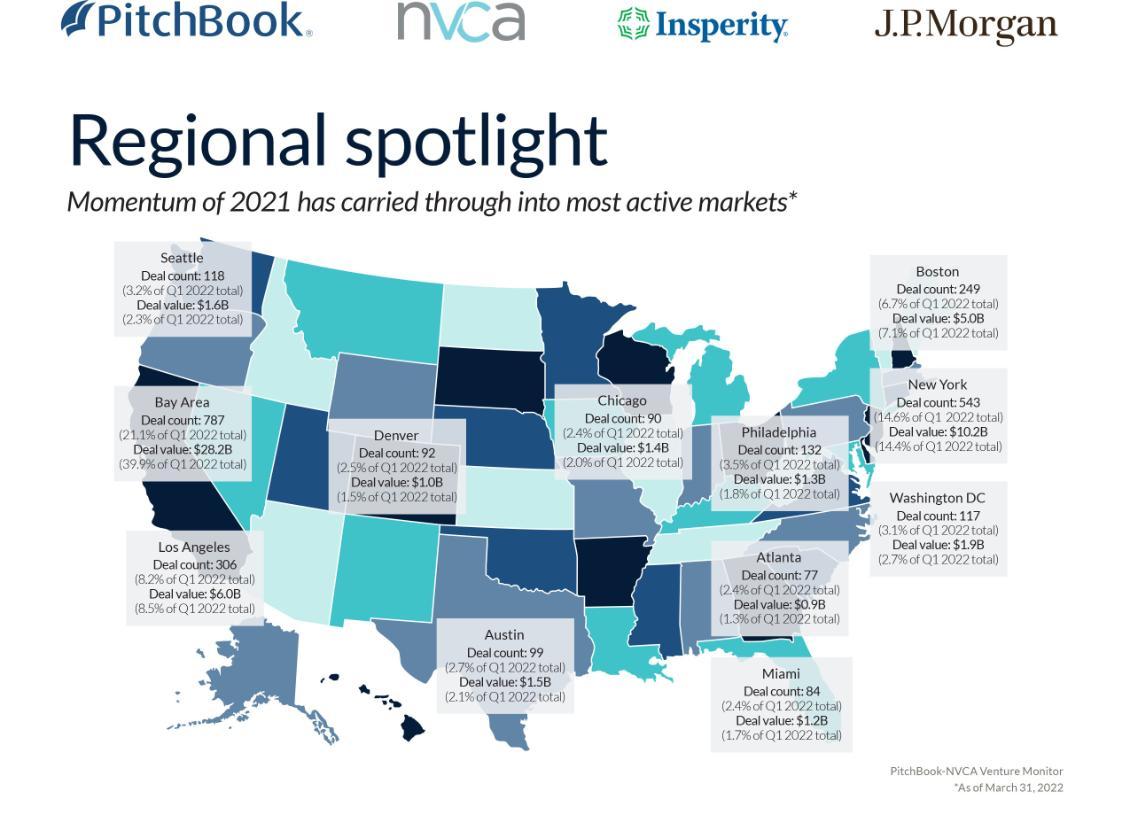

Infographic: Past Harriet Stephenson Business Plan Competition Winners

Updated: Tuesday, May 31, 2022

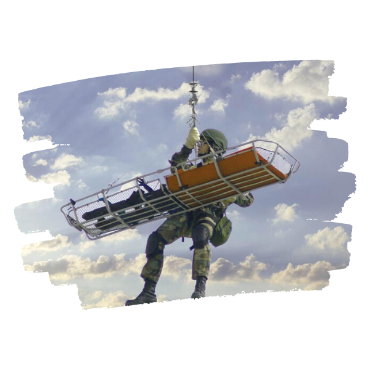

Creator of the world's first autonomous system that stabilizes loads under helicopters and cranes

Total funding amount: $27.3 million

Portable, dairy-free, plant-based creamers with no added sugars or sweeteners

Total funding amount: $35.1 million

Healthcare service provider that delivers comprehensive, intelligent primary care to employees via employer-funded worksite clinics

Total funding amount: $95.5 million

How has entrepreneurship evolved over the years? Where do you think it is headed?

We are in the middle of our 24th business plan competition. Many of our winners are still running the business they started during this competition. Yet, recently when I was recruiting a judge for the competition, I asked them when was the last time they read a business plan and they nearly rolled their eyes.

This is one of the major ways that entrepreneurship has evolved. It used to be linear: first, you come up with a killer idea, second, you write a killer business plan, third, you recruit a great team, then execute. It just does not work like that anymore. Technology and information access has made it a lot easier to test ideas cheaply and get feedback without needing to invest tremendous amounts of time or money in back of the napkin concepts.

This has not done away with planning, but it has done away with the linear business plan process. Now, it is all about traction and social proof. Can you find a real problem out there that needs to be solved? Can you identify a constituency that wants that problem solved so badly they are willing to pay for a solution? If yes, you are on your way.

I don’t think there is such a thing as the next big thing under these new technology conditions. I think it's all about execution. Any team, if they work hard, can find a problem worth solving and build an impactful business in the process. In this environment, I don’t bet on ideas. I bet on people.

What do you think are entrepreneurship’s biggest challenges? For instance, diversity is still not where we’d want it to be.

I do think the legacy startup community -- the one that we traditionally celebrate -- has a huge homophily problem. I play this game with my students where I ask them to think of a successful entrepreneur and then pretend to be psychic. Does it really make sense that I am almost always right because everyone is thinking of the same half dozen people?

Infographic: The Inequality Gap in Startups

Source: Harvard Business Review

Source: Crunchbase

Source: Harvard Business Review

Surely, a lot of this is media driven -- you know, history getting written by the victors and all that. Also, our case method has a problem of survivor bias. Since so many startups fail, we tend to be laser focused on the wildly successful outliers.

But what is there to learn from them really? Isn’t there more to learn from the rest of the successful small- and medium-sized firms that make up most of the economy? Isn’t there also a lot we can learn from the failures?

Often timing was as important as anything else in their success; I know it has been often with my own entrepreneurship. Sometimes just showing up was enough to make things work out well enough. That’s just not true for a lot of people.

I used to think that entrepreneurship was a level playing field because everyone started with nothing, but I’ve come to realize that this does not mean that everyone starts in the same place. Some of us had significant advantages at the starting line or along the way.

One huge wake up call for me in teaching entrepreneurship has to do with the subject of failure. We’ve always taught students that failure was to be celebrated and worn as a badge of honor for entrepreneurs, that future stakeholders (investors, partners, etc.) would see their failures as learned experiences, lessons not to be repeated, credits to your account.

However, more recent entrepreneurship research shows this sadly not to be the case for most startup founders. In fact, failure is often only an asset if you are not a woman, not a minority, not an immigrant. If you are one of the latter, failure tends to be held against you in your next venture. That may one of our biggest challenges in entrepreneurship today -- I know at least it is my biggest challenge in teaching it.

What were some of the most exciting entrepreneurial ventures you’ve been part of if in your lifetime, whether as an advisor, mentor, or investor?

I guess there are two and they couldn’t have been more different. The first was, well, my very first business. I started a house painting business in Maine right after high school. I sent a cold direct mailing letter to 1,500 summer residents of a little town where my family went every summer with my pitch and got two responses. It was like some kind of magic.

My parents would not let me live up there by myself unless I had a job and, abracadabra, I just made myself a job. I had that company every summer in college.

The other one predictably was Redbox (my students reading this are probably already groaning since I seem to never stop with this Redbox stuff). It’s a neat story though because it was what you might call a ‘burning platform’.

When we first invested in Redbox, we knew that the DVD rental business was going away, being replaced by streaming. In fact, when I first pitched it to the Coinstar board of directors, I asked them to raise their hands if they thought DVDs would be around forever. When no one did, of course, I suggested that the only important question was how long?

We placed a bet on a business that we knew would peak in seven to 10 years and that’s exactly what happened. It was terrifying and exciting all the same to experience incredible growth but know for certain that it was going to end. As I mentioned before, timing is important.

During your time at Coinstar, the company grew from $150 million to $1.3 billion in revenue. You led more than 20 acquisitions, investments, and divestures, including the investment in Redbox. Not everyone has a front-row seat as you did with a company that grew as quickly as Coinstar. What were the lessons that you took away from this experience?

Gravity is real. What goes up really does come down. The bigger organizations get, the more difficult it is to maintain their growth. They become big, sloppy, and packed with administrative waste. This is awesome. I mean it. It is a huge opportunity for entrepreneurs.

I made my whole entrepreneurial career -- mostly trying and failing, of course -- out of trying to disintermediate the big guys. Coinstar did it to the banks with the coin counting machines. Redbox did it with the DVD kiosk. I told you we tried to do it with coffee. We also tried with printer ink, with photo printing, gift cards. I don’t have space or time here to mention all the things we tried that never got traction.

But then something funny and interesting happened: Coinstar got big and sloppy too. That is just the way of things, I suppose. There are very few very large organizations that have been able to maintain an agile, innovative mindset while having a positive impact on the world. In many ways, corporate growth is incompatible with positive social impact.

That’s one of my big lessons and something that I hope to learn from my students. They are the ones who will figure out how to create businesses that can grow and be sustainable without making costly environmental and societal choices in the name of shareholders. We never figured out how to do that. I hope to help my students figure that out.

Rowan talks more about his plans for the Innovation & Entrepreneurship Center in this GeekWire story.