The third and final chapter in our ongoing story about Professor Marissa Olivares and her experiences at Seattle University this year.

As she nears her final weeks as Seattle University’s first Fulbright Scholar-In-Residence, Professor Marissa Olivares is balancing a sense of celebration for future plans here in Seattle with deep concern for her family, friends and higher education colleagues at home in Nicaragua.

As she nears her final weeks as Seattle University’s first Fulbright Scholar-In-Residence, Professor Marissa Olivares is balancing a sense of celebration for future plans here in Seattle with deep concern for her family, friends and higher education colleagues at home in Nicaragua.

“My experience at Seattle University has been so memorable. Working with the students has been a joy. I am looking forward to continuing to work in Seattle next year. At the same time, it is very difficult to watch what is happening in my home country.”

This fall, Professor Olivares will begin doctoral studies in International Studies at the University of Washington while working with students at SU, continuing her contributions to Seattle University’s Central America Initiative, and serving as a resident minister for SU’s Xavier House. “I am so pleased that she will have the opportunity to keep working with our students,” said Dr. Serena Cosgrove. “She will also work with me in Central America classes and programming for the Central America Initiative.”

Professor Olivares and Dr. Cosgrove were recently interviewed for an article in America: The Jesuit Review, “With a ‘sham trial’ of a Nicaraguan bishop about to begin, a clampdown on the nation’s Catholic Church continues.” From the article, “…‘All the [civic] spaces are closed in my country,’ Ms. Olivares said. ‘Nobody is saying anything in the media, in the social networks; everybody is shut down because everybody is afraid.’ And now that silencing has extended to the church, she says, a source of frustration to average Nicaraguans. In the past, she says, Nicaraguan clergy stood fearlessly on the side of oppressed people. But now ‘the strong priests are in jail or in exile,’ she concludes.”

The Nicaraguan government has closed 19 private universities and is enforcing strict limitations on curriculum at the public universities. Universidad Centroamericana (UCA), one of Seattle University’s partner universities and where Dr. Olivares teaches, is still open. However, since the government now controls accreditation, technically the university is not accredited. Professor Olivares explained, “The government created a new institution in charge of everything the universities do, what they teach, research, even the movement of faculty and students. The university has to report and ask for permission for a professor to travel outside the country, even if it is personal travel.”

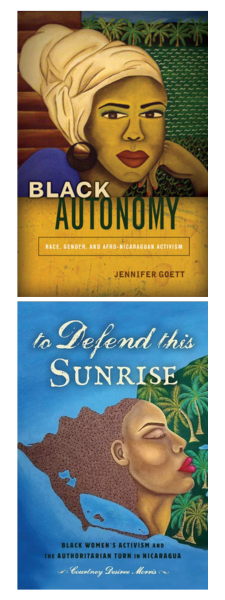

This Spring quarter, Professor Olivares is leading an independent study course, “Women’s Leadership on the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua.” Four students are engaged in a reading group about the activism and inclusion of Afro-descendant women on Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast, who are often marginalized due to race, class, gender, and location. They are focused on two books that celebrate women’s leadership, resistance, and persistence given the racialized patriarchy of Mestizo nationalism and extractivist capitalist practices that exclude the Caribbean coast and its peoples from the national imagination of country and belonging. The books are Black Autonomy: Race, Gender, and Afro-Nicaraguan Activism by Jennifer Goett and To Defend This Sunrise: Black Women’s Activism and the Authoritarian Turn in Nicaragua by Courtney Desiree Morris. They are also exploring women’s organizing on the Caribbean coast to protest the authoritarian measures being pursued by the current regime.

This Spring quarter, Professor Olivares is leading an independent study course, “Women’s Leadership on the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua.” Four students are engaged in a reading group about the activism and inclusion of Afro-descendant women on Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast, who are often marginalized due to race, class, gender, and location. They are focused on two books that celebrate women’s leadership, resistance, and persistence given the racialized patriarchy of Mestizo nationalism and extractivist capitalist practices that exclude the Caribbean coast and its peoples from the national imagination of country and belonging. The books are Black Autonomy: Race, Gender, and Afro-Nicaraguan Activism by Jennifer Goett and To Defend This Sunrise: Black Women’s Activism and the Authoritarian Turn in Nicaragua by Courtney Desiree Morris. They are also exploring women’s organizing on the Caribbean coast to protest the authoritarian measures being pursued by the current regime.

“I could not teach this class at my home university now,” said Professor Olivares. “Topics like human rights and words like democracy and conflict are prohibited. For example, we had a class at UCA, “Peace and conflict resolution” that is now closed since we talked openly about the history of conflict in Nicaragua.”

Research and student work at private and public universities are also affected. Speaking of a colleague at UCA, Professor Olivares said, “They have had a research project about memories of the hot theme of the environment in the Caribbean Coast on hold for six months. They have to be patient, as it is not a good time to raise the subject and attract attention.” She also points out the effect on students at universities under government control, “They are under stress because all of the time their papers, their essays, their research must reproduce the idea that the country lives in peace, as though nothing has happened. They are basically forced to publish propaganda.”

“The president and vice president of the country have pretty much complete control over the country right now,” added Dr. Cosgrove. “As outlined in the America magazine article, ‘…more than 328,000 people—about 5 percent of the country’s population of 6.7 million—fled Nicaragua last year. The New York Times reports that the number of Nicaraguans seeking asylum in the United States has spiked to the top of U.S. border patrol lists. By the end of November 2022, more than 180,000 Nicaraguans had crossed into the United States—about 60 times as many as the number who sought entry during the same period two years ago.’”

During this interview, when a comment was made about the difficulty of imagining living in this kind of authoritarian regime, with such severe suppression, Dr. Cosgrove agreed how that could be true for many of us Americans. “However, if you look at what is happening in Florida now and the control over higher education, you see that they are using techniques similar to those of the Sandinistas. They are using accrediting processes, putting pressure on publicly appointed university leaders to go along with the idea of not teaching classes about certain things. People are threatened with losing their jobs, so they are scared and not speaking out about what is really going on.”

In the America magazine article, Professor Olivares expressed her sympathy for those unwilling to speak out. “I can’t judge because I’m not in Nicaragua…I am talking freely to you here in the U.S. It’s not easy to speak loudly in Nicaragua,” but “the feeling against this regime is just despair.”

She does have hope for the future. “I have been able to see and learn from Seattle U academic culture and policies and I can imagine the future development for UCA. Also, few UCA professors have earned their PhDs and I look forward to taking my experience back there.”