No Caption Provided

December 14, 2022

President Peñalver shared the following remarks with the Seattle Art Museum’s Board of Trustees on Dec. 13.

Art is a commodity . . . a very valuable commodity.

People buy and sell art. They use it as a vehicle for storing wealth. They treat it as an investment. They speculate in it.

Sotheby’s maintains the Mei Moses All Art Index, which tracks artworks with repeat sales and compares their aggregate performance to the S&P 500. A number of art investment funds, such as Masterworks, securitize art and allow retail investors to include it within their portfolios. Masterworks, for example, allows you to own 1/800 of a Basquiat. In 2021, the aggregate value of transactions in art and antiquities around the world was over $65 billion.

So, yes, art is most definitely a commodity. But art is a weird kind of commodity, and it is weird for at least three reasons. First, when compared with other forms of movable property (what the law calls “personal property” or “chattels”), individual pieces of art are unusually valuable. They are also nonfungible. Both of these aspects of art have interesting consequences, which I will discuss. Second, as the physical embodiment of the creative insights of the artist, art is a vehicle that conveys powerful concepts and ideas, and ultimately for the personhood of the artists themselves. Finally, and because of that connection to an artist’s personality, even those who do not own a work of art can form meaningful relationships with it. And, in the case of artists, those relationships have legal consequences, thereby complicating what it means to “own” a work of art.

Let’s start with the first reason art is a “weird” commodity: the high value of individual works of art and their nonfungibilty. Why does this matter?

In American law schools, we teach our students by examining the decisions courts make to resolve actual cases and controversies. In part we do this because the courts themselves look to prior decided cases to resolve new disputes

Litigation is expensive. So reported cases tend to involve property that is valuable enough to be worth paying a lawyer to fight over. Even though very few people are fortunate enough to own valuable works of art, there are actually a fair number of reported cases about them. This gives art, and art owners, an outsized influence on the development of our property law.

In addition to their high monetary value, works of art’s nonfungibility – their uniqueness – lends them a special status within our property law, a status we associate more with land (and homes) than with chattels. Art is the only category of personal property for which the law routinely orders the remedy of “specific performance” for breach of a sales contract. That is, courts will order the actual transfer of a work of art as opposed to merely the payment of contract damages. Courts generally accept that the failure to deliver a promised piece of art cannot be adequately remedied by money. Money (or even a different piece of art) simply cannot substitute for the specific promised work.

The second way in which art is a weird commodity relates to its service as a vehicle for representing the ideas and insights of the artist. To my mind, this feature of art is brought out in an exceptionally clear way by the work of conceptual artists like Felix Gonzalez Torres. This piece, for example, is called “Portrait of Ross in LA.” It consists of 175 lbs of hard candy, typically arranged in a corner. It is owned by the Art Institute of Chicago. Felix Gonzalez Torres created it to honor of his partner, Ross Laycock. 175 lbs was Ross’s healthy weight. Patrons who view it are encouraged to take some candy home with them. In doing so, they re-enact (over and over again) Ross’s gradual wasting away as he grew sick and died of AIDS.

The second way in which art is a weird commodity relates to its service as a vehicle for representing the ideas and insights of the artist. To my mind, this feature of art is brought out in an exceptionally clear way by the work of conceptual artists like Felix Gonzalez Torres. This piece, for example, is called “Portrait of Ross in LA.” It consists of 175 lbs of hard candy, typically arranged in a corner. It is owned by the Art Institute of Chicago. Felix Gonzalez Torres created it to honor of his partner, Ross Laycock. 175 lbs was Ross’s healthy weight. Patrons who view it are encouraged to take some candy home with them. In doing so, they re-enact (over and over again) Ross’s gradual wasting away as he grew sick and died of AIDS.

A work of conceptual art is necessarily abstract and intangible – the work itself (the enduring object) cannot be touched or felt or possessed. “Portrait of Ross” consists not of the individual pieces, or even the individual piles, of candy, which are constantly being taken up and replenished. At the most basic level, the work consists of the idea of 175 lbs of hard candy arranged in a corner. But it also embodies other ideas as well: about life and loss and about the public’s complicity in the slow government response to the HIV epidemic in the 1980s.

And yet the work is simultaneously a valuable commodity worth many millions of dollars. (A similar piece sold for nearly $5 million in 2010.) But what does it even mean to own a commodity like this: one whose physical substance is constantly turning over, continuously being depleted by gallery patrons and renewed by diligent curators? What does it mean to buy this work or to sell it? What would happen if SAM displayed Portrait of Ross without the permission of the Art Institute? What harm would the Art Institute suffer?

These are fascinating legal and conceptual questions that push at the limits of our understanding of art, of objects, and even of “ownership” itself. I suspect these puzzles were an important part of what Felix Gonzalez Torres was trying to explore with his challenging work. But, while Gonzalez Torres’s work brings these questions to the foreground, they are always there, lurking over even more traditional work.

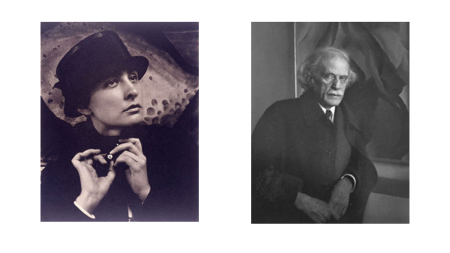

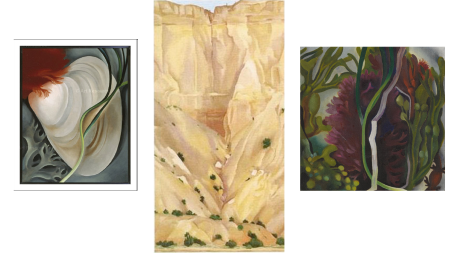

In its physical embodiment of the artist’s ideas and insights (and this is my final point about why art is a weird commodity), art comes to possess a deep, almost existential connection to the artist. One of the most famous art-property cases illustrates the strong and enduring bond an artist forms with her creations. The case involved a dispute between Georgia O’Keefe and Barry Snyder, the owner of a New Jersey gallery.

Snyder had purchased three of O’Keefe’s early paintings. When she learned of his possession of them, she claimed they had been stolen 30 years earlier and demanded their return. (The facts are murky and contested. It is possible that the paintings had been stolen. But it is also possible that they had been given away without O’Keefe’s knowledge by her then-husband, the photographer, Alfred Steiglitz. O’Keefe did not report a theft at the time the paintings went missing.)

Snyder had purchased three of O’Keefe’s early paintings. When she learned of his possession of them, she claimed they had been stolen 30 years earlier and demanded their return. (The facts are murky and contested. It is possible that the paintings had been stolen. But it is also possible that they had been given away without O’Keefe’s knowledge by her then-husband, the photographer, Alfred Steiglitz. O’Keefe did not report a theft at the time the paintings went missing.)

Years of litigation led to a very influential opinion by the New Jersey Supreme Court concerning the ability of good faith purchasers of stolen property to acquire clear title if the original owner does not exercise due diligence in searching for the property. O’Keefe and Snyder ultimately settled the case. Each received one of the paintings and they sold the third to pay for the lawyers.

O’Keefe’s decades long attachment to her paintings, her willingness to litigate for years to get the paintings back, points to the powerful bond an artist forms with her work, even work she produces with the intent to sell. In many European countries, the law recognizes this robust bond by giving artists the right to prevent the mutilation or alteration of their works even after they have been sold. This legally protected interest is called a moral right.

Until relatively recently, moral rights were not recognized in the United States. In 1990, however, Congress enacted the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), granting living artists right to protect “works of visual art” that they create. For works created after the effective date of the statute, June 1, 1991, the law grants the artist the right to prevent “any intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of [the] work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation,” 17 U.S.C. §106a(a)(3)(A), and to prevent any intentional or grossly negligent destruction of a work of “recognized stature,” id. §106a(a)(3)(B).

The most complex and interesting cases under the VARA arise when a work of art is affixed to a building or structure, for example, when a mural is painted directly onto a wall or otherwise incorporated into the building. In these cases, as long as the work is of significant stature, VARA gives the artist the power to prevent its destruction and therefore the extraordinary power to control whether a building – which the artist does not own – is renovated, destroyed, or redeveloped.

But in extending this extraordinary protection only to works of “recognized stature,” VARA brings into the conversation yet another party with an interest in the art – neither the artist who created the work nor the person who currently owns it: the public (including critics) who receive the art and confer on it the special cultural significance the law refers to as “stature.”

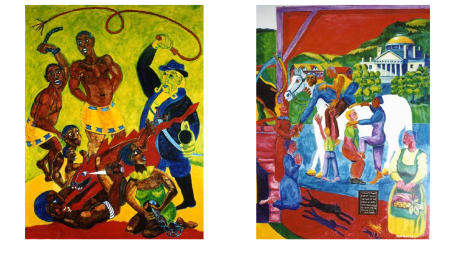

One recent case captures the complex and shifting web of interactions among art, its owner, the artist, and the public. In 1994, the artist Samuel Kerson conceived of an idea for two murals depicting Vermont’s role in the Underground Railroad, and its efforts to help enslaved people seeking freedom in the years prior to the Civil War. The University of Vermont Law School agreed to allow him to paint the murals on the interior walls of one of its buildings. The murals were well received and existed without controversy for many years. But in early 2020, Vermont Law School received several complaints from students, who objected to the caricatured style in which Black people were depicted in the paintings. In response, the law school announced that it planned to paint over the murals.

One recent case captures the complex and shifting web of interactions among art, its owner, the artist, and the public. In 1994, the artist Samuel Kerson conceived of an idea for two murals depicting Vermont’s role in the Underground Railroad, and its efforts to help enslaved people seeking freedom in the years prior to the Civil War. The University of Vermont Law School agreed to allow him to paint the murals on the interior walls of one of its buildings. The murals were well received and existed without controversy for many years. But in early 2020, Vermont Law School received several complaints from students, who objected to the caricatured style in which Black people were depicted in the paintings. In response, the law school announced that it planned to paint over the murals.

Kerson objected, claiming that doing so would violate his rights under VARA. The law school conceded this point but responded that Kerson could either remove the murals at his own expense or the law school would cover them with acoustic tiles, leaving the painting undamaged beneath. Kerson sued in the federal district court, claiming there was no way to remove the murals without damaging or destroying them, and that covering them, even in a non-destructive manner, would violate his rights. The law school sought to dismiss his complaint, arguing that nothing in VARA prevents the law school from covering the artwork, preventing its exhibition without destroying it.

The law school ultimately prevailed. As interesting as the specific outcome of this case is the fact that it arose at all. The dispute illustrates nicely the powerful feelings that art elicits, not just for owners, but for artists and for members of the viewing public, each of whom feels some sense of entitlement over the work.

The law school ultimately prevailed. As interesting as the specific outcome of this case is the fact that it arose at all. The dispute illustrates nicely the powerful feelings that art elicits, not just for owners, but for artists and for members of the viewing public, each of whom feels some sense of entitlement over the work.

In this case, the students wanted the work removed because it offended their sense of how Black people ought to be depicted in public art. The artist saw the work as a reflection of his own personality and stature. He was proud of it and wanted it to continue to be available for public viewing.

The law left it to the owner to decide whose views should prevail. But it limited the scope of the owner’s prerogatives, recognizing the power to cover the painting but not to damage or destroy it, at least during the artist’s lifetime.

To conclude – people often think of property ownership as a simple legal relationship between an owner and an object – a commodity. Billion-dollar art markets implicitly affirm and rely on that conception of art as commodity.

But art is a weird commodity. As an expression of an artist’s ideas and insights, it continues to embody the artist’s personality even after the artist parts with it. In addition, those who view the art form their own relationships with it: they become attached to it or sometimes they come to be repulsed by it in ways that create public controversy and new public meanings for a work of art, as the Vermont case illustrates. Far from a mere commodity, art is the nexus for a complex web of social relationships among the work, its owner, the artist who created it, and the many people who come to love it … or hate it.