No Caption Provided

April 12, 2024

President Peñalver shared the following talk during Seattle University’s Mission Day gathering for faculty, staff and students on April 11, 2024.

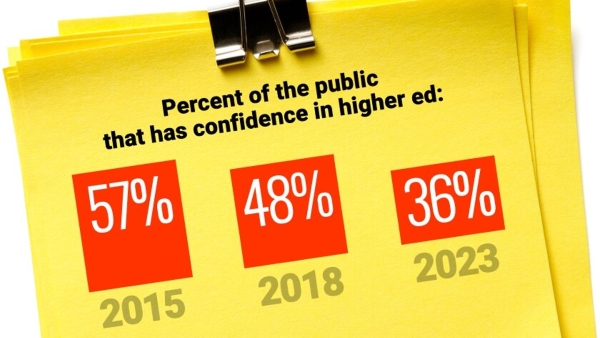

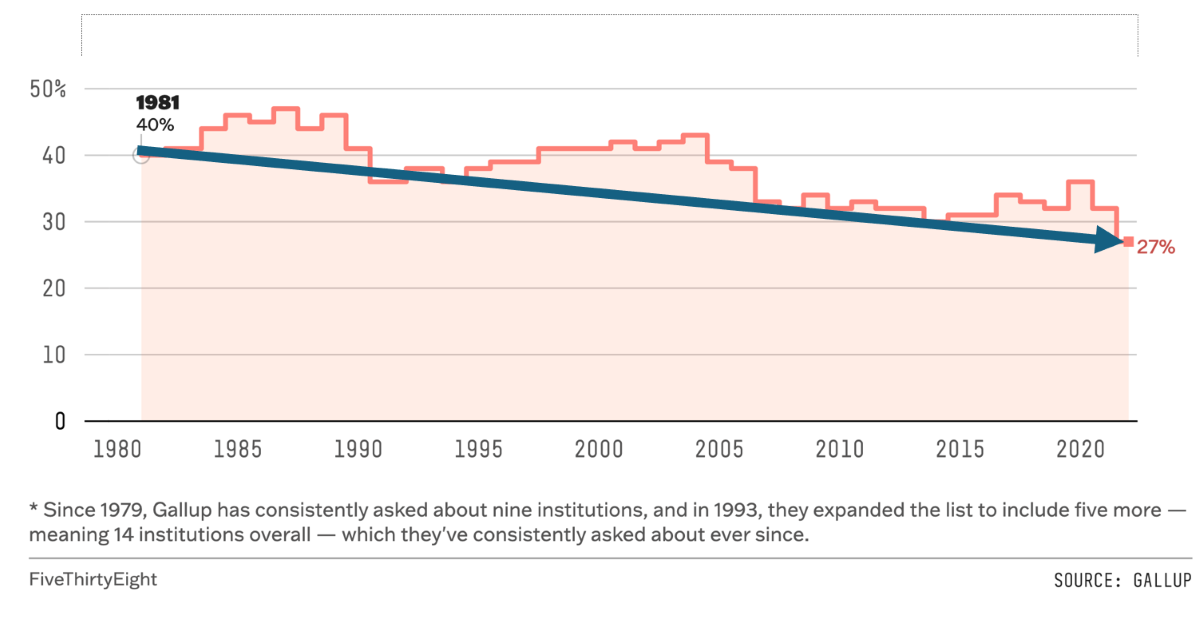

Over the past few years, trust in higher education has been declining more rapidly in this country than for any other category of institution.

This declining trust sits within the context of a loss of trust in American institutions more generally tracing back to the 1970s.

But it also comes after decades of universities successfully resisting that broader trend.

But it also comes after decades of universities successfully resisting that broader trend.

These days – and it seems particularly acute this year – higher education feels adrift.

Universities are struggling to articulate our contribution to society – struggling to communicate or even to understand how the work we do on campus helps society to address the many challenges it faces off campus.

The context in which universities and Seattle University find ourselves these days qualifies as “rough waters.”

(And, yes, this image was generated by AI.)

Saint John Henry Newman described the sense of mission at Catholic universities as a kind of ballast that steadies the university, helping it to navigate rough waters.

Sitting as it does, beneath the waterline, ballast can be easy to overlook. But, especially in times like these, the ballast provided by our university’s Jesuit mission serves as a reminder of why it is such a privilege to work here. That privilege is rooted in the 500-year old Jesuit educational tradition, which we harness to empower our students to become leaders for a just and humane world.

Mission Day provides an opportunity for us to step away from our daily routine to reflect more deeply on the distinctive nature and meaning of our work as a Jesuit Catholic university.

Newman defined the university as “a place for teaching universal knowledge.”

We share that commitment to the pursuit and transmission of knowledge and truth with all universities. But, at a Jesuit university, we add to it several characteristics distinctive of Catholic institutions.

In their book on Catholic higher education, What We Hold in Trust, Don Briel and his co-authors identified two key elements of the Catholic approach:

(1) The first is a commitment to what they call “the unity of knowledge”: “Because the world is a cosmos created by a God of order,” they say, “there is a coherence in all that exists, and a resulting coherence between the order of reality and the enterprise of gaining human knowledge. . .” At a Jesuit university, one important way we manifest our respect for the complex unity of knowledge is through our commitment to interdisciplinarity as an essential feature of a well-rounded education.

(2) The second key element, according to Briel and his co-authors, is a “commitment to the complementarity of faith and reason.” “Grasping the entirety of truth,” they argue, “demands different modes of understanding and investigation.”

Although Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book, Braiding Sweetgrass, is not written from an explicitly Jesuit or Catholic perspective, its insights fit very comfortably with our guiding commitments to the unity of knowledge and to the complementarity of faith and reason.

By way of example, consider Wall-Kimmerer’s story about asters and goldenrod.

In an early chapter in the book, Wall-Kimmerer describes her arrival at college as a first-year student, intent on studying botany. When asked by her academic advisor why she had chosen this major, she tells him, “I chose botany because I wanted to learn about why asters and goldenrod looked so beautiful together.”

Her advisor, certainly no Jesuit, “laid down his pencil as if there was no need to record what [she] had said. ‘Miss Wall,’ he said, . . . ‘I must tell you – that is not science. That is not at all the sort of thing with which botanists concern themselves.’ . . . And if you want to study beauty, you should go to art school.”

(What he should have said is, “if you want to study beauty, you should have gone to a Jesuit university.”)

Wall Kimmerer goes on to report that the botany she was taught in her undergraduate college was “reductionist, mechanistic, and strictly objective.”

From within the Catholic intellectual tradition, Wall Kimmerer’s botany professor exhibited characteristics of a worldview that Pope Francis has called “scientism.”

In his Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, Francis describes scientism as a view that “refuse[s] to admit the validity of forms of knowledge other than those of the positive sciences.”

In contrast to a narrow scientism, the Catholic intellectual tradition “proposes another path, which calls for a synthesis between the responsible use of methods proper to the empirical sciences and other areas of knowledge such as philosophy, theology, as well as faith itself, which elevates us to the mystery transcending nature and human intelligence.” (Evangelii Gaudium)

Wall Kimmerer describes indigenous ways of knowing in very similar terms. Citing another indigenous scholar, she says that “we only understand a thing when we understand it with all four aspects of our being: mind, body, emotion and spirit,” (p. 47) words that should sound familiar to anyone who has experienced the Jesuit educational tradition.

Even while criticizing the narrow rigidity of scientism, Pope Francis has been adamant in opposing “relativism” or “perspectivism,” which he identifies with a radical individualism that is alien to the Catholic worldview. The truth – he says – is not “variable and subjective.”

Wall Kimmerer similarly insists that acknowledging multiple ways of understanding or reaching the truth does not mean asserting the existence of many truths. “After all,” she says, “there aren’t two worlds, there is just this one good green earth.”

The infelicitous locution “my truth” or “your truth” – which I have heard with greater frequency in recent years – is suggestive of a very different conception of knowledge and often acts as a conversation stopper.

But not everyone who engages in this way of speaking actually intends to reject the idea of a shared truth.

In fact, I would argue that most people who speak this way still accept the notion of shared truth, at least implicitly. I say this because many of these same speakers also want to make claims of justice that are binding on others. But any claim of justice becomes meaningless – except as an assertion of raw power – if it is not rooted in a shared reality.

The locutions “my truth” or “your truth,” can perhaps be reconciled with an affirmation of the unity of knowledge – with shared truth – if we understand them as a shorthand for the following: “my limited and tentative perspective on the truth, a perspective that is susceptible to error or distortion rooted in my own human experience, but that – by the same token – has something important to contribute to your understanding (or perhaps our shared understanding) of the complex and multifaceted truth.” Understood in this way, the assertion becomes not a conversation stopper but rather an invitation to further dialogue.

Precisely because there is only “one good green earth,” to use Kimmerer’s words, the truth about it must be – like the earth itself – complex and multifaceted, even in its unity.

Kimmerer’s affirmation of the unity of truth and knowledge is perhaps the reason she does not withdraw from engagement with the academic discipline of botany or refuse to subject her intuitions about asters and goldenrods to scientific scrutiny.

Even as she insists that science is not the whole story, she enthusiastically explores the evolutionary biology and the neuroscience of color to explain how purple asters and yellow goldenrods complement one another, enhancing their combined attractiveness to pollinators, such as honeybees:

“Their striking contrast when they grow together makes them the most attractive target in the whole meadow, a beacon for bees. Growing together, both receive more pollinator visits than they would if they were growing alone.

"It’s a testable hypothesis; it’s a question of science, [but also] a question of art, and a question of beauty. Why are they beautiful together? It is a phenomenon simultaneously material and spiritual, for which we need all wavelengths, for which we need depth perception.”

I can’t think of a more apt description of the holistic kind of knowledge that Seattle University hopes to impart to our students than “depth perception.”

Wall Kimmerer’s insistence on cultivating depth perception encourages her to dig deeper and to cast a wider net than her more narrow-minded academic advisors.

At the same time, when Wall-Kimmerer is doing science, she embraces the tools and standards of her academic discipline. She may be willing to ask questions that her professors refused to credit, but she does not see that as permission to be a less-than-rigorous scientist.

In fact, she takes her undergraduate advisor to task on his own terrain of academic excellence. Had he been a better scholar, she correctly insists, he would have celebrated her novel questions and not dismissed them out of hand. He was held back by the limited scope of his conversations and by the anti-intellectual narrowness of his own imagination.

By bringing her distinctive, broader perspective to the discipline of botany, Wall Kimmerer has enriched its frame – and her impact was enhanced by her willingness to join the conversation on at least some of its own terms.

Like Wall Kimmerer’s intellectual project, Seattle University’s Jesuit Catholic mission embraces a unitary conception of knowledge that simultaneously affirms inclusive and interdisciplinary approaches to its pursuit.

Our Jesuit affirmation of the unity of knowledge undergirds our commitment to academic excellence AND to including voices and viewpoints that have been excluded or that may still be missing from many academic conversations.

Our Jesuit mission pushes us to value a diversity of experiences AND perspectives that broaden the scope of our collective conversations and our search for truth – in short, our Jesuit education aspires to impart “depth perception.”

I hope that today’s conversations deepen your perceptions and help you to uncover new pathways to the truth.