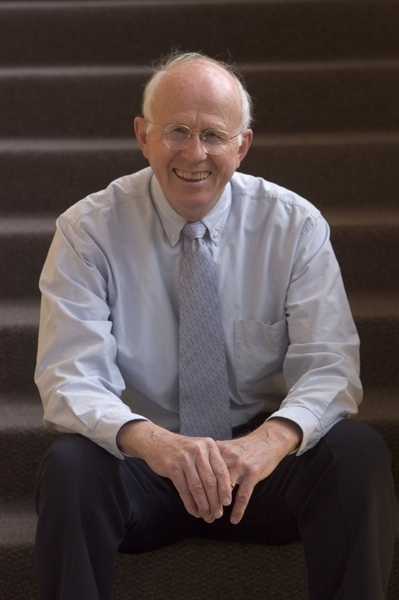

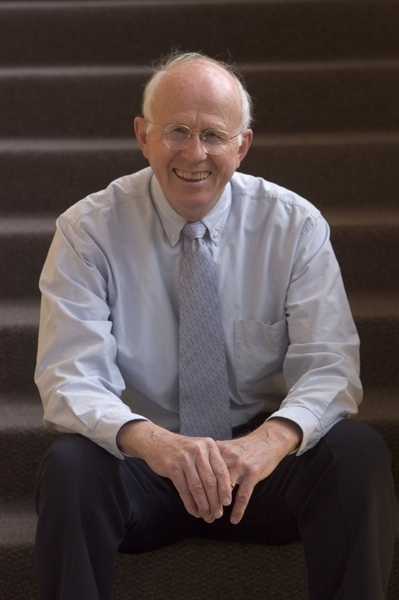

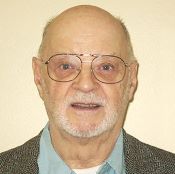

Update – Jan. 31, 2023: Bob Harmon's obituary

Update – Jan. 31, 2023: Bob Harmon's obituary

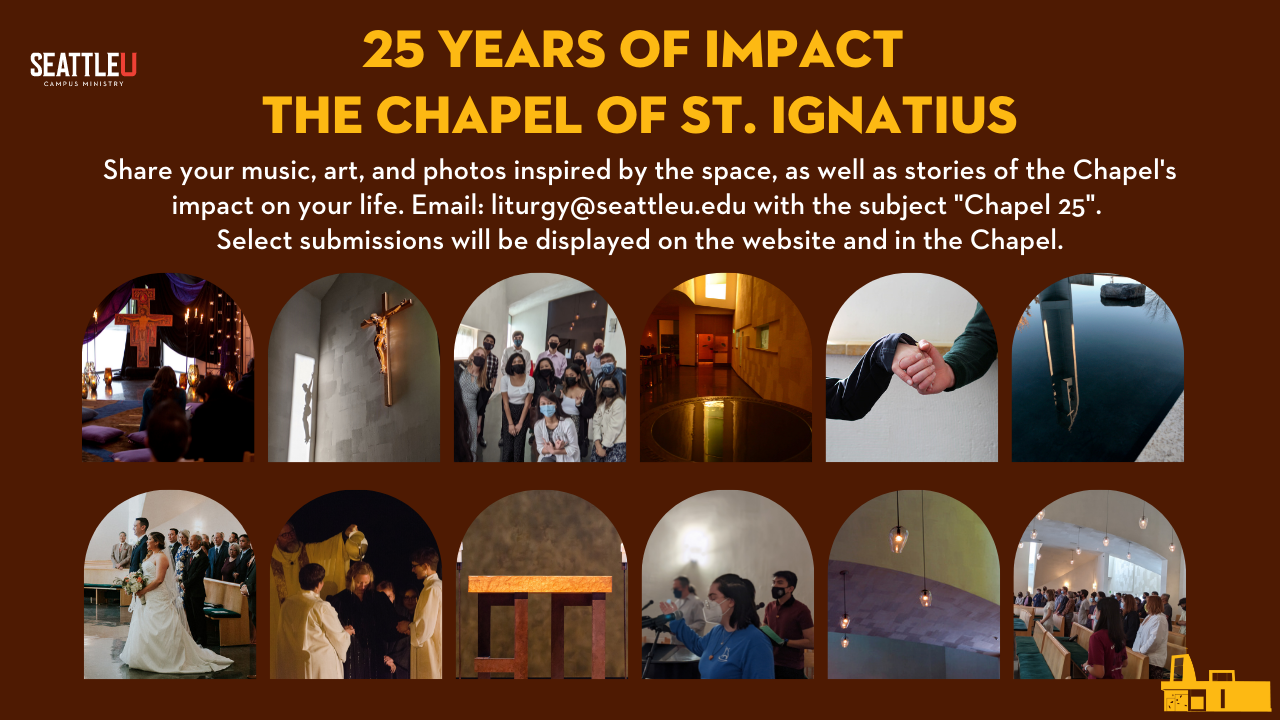

Update – Jan. 30, 2023: Following is an extended version of the eulogy SU alumna Chris Harmon delivered today at the funeral of his father Professor Emeritus Charles Robert (Bob) Harmon, '51, at the Chapel of St. Ignatius. Visit Remembering Bob Harmon for the announcement shared with campus on Jan. 26.

The passing of Charles Robert Harmon on January 22nd was a quiet event but one of great significance. Virginia, Jeannie, David, Teri and I have all had the experience of being somewhere unusual in America, or overseas, and being surprised to meet yet another student or friend of Bob Harmon. Beyond the family, and beyond the thousands of the Seattle University community, there are hundreds more he touched. The family would like to say “Bless you for all you did to make his world so wide and so good.”

Bob always made you think he felt privileged to have your company. And… I think you’ll agree….he also earned your friendship with his merits. It was an astonishingly rich collection of attributes. I shared six decades without a feeling of exploring all the virtues or all the knowledge of this man—not the half.

One day, a few Harmons were together just after the J. Paul Getty Museum opened a building, outside Los Angeles, a magnificent villa on Pacific Coast Highway. We were admiring Roman heads, Greek statues, stone arches like those Dad and Mom had shown us kids in living room slide shows on East Galer Street in Seattle. Our little party wandered and gradually separated, and after a while I moved into a room with a few European paintings—including one brand new Getty acquisition. My father was already there; he was standing before an oil, “Man With A Hoe” by Jean-Francois Millet. A rural scene in France, about 1860: an exhausted farmer, who has been hoeing in a field of dirt, thistles and stones. Apparently when this painting was shown in Paris it scandalized the bourgeoisie; they did not want to see the harshness of a peasant’s laboring life.

As I walked over to my father he began, very quietly, speaking lines the Oregonian poet Edwin Markham had written after seeing this same painting:

“Bowed by the weight of centuries he leans

Upon his hoe and gazes on the ground,

The emptiness of ages in his face,

And on his back the burden of the world.

Who made him dead to rapture and despair,

A thing that grieves not and that never hopes,

Stolid and stunned, a brother to the ox?

Who loosened and let down this brutal jaw?

Whose was the hand that slanted back this brow?

Whose breath blew out the light within this brain?”

….

“O masters, lords and rulers in all lands,

Is this the handiwork you give to God,

This monstrous thing distorted and soul-quencht?

How will you ever straighten up this shape;

Touch it again with immortality;

Give back the upward looking and the light;

Rebuild in it the music and the dream….”

Edwin Markham gives us a new view of a man with a hoe, and, for me that day, a new facet of Charles Robert Harmon. Here was a little epiphany for any student brought to the right spot by luck. Dad knew the story of Millet’s disturbing painting, and responded with all the respect the painter would have wanted. He knew the Markham poem—it was one of “101 Famous Poems” between the blue covers of this little edition you may have seen at his home. Here for me was a glimpse of what it really means to offer a liberal education, another bright flash off the long glittering stream that was his teaching life.

That happened long ago and I’ve never told the story. As each of you knows, there are too many true stories just as valuable to be told today. Everyone who knew him well has seen many things, just as illuminating. Sometimes personal, maybe profound. Sometimes the flash was of wit -- my friends in college began writing down the one-liners from classes. They made a broadsheet of them, with a caricature of Bob Harmon; Cyndi, and Brad, and Karen—he kept your poster for decades.

Kids -- college kids -- would come into Bob’s company for reasons that were academic and then many stayed on because of his character. We were young; we didn’t know much. But when a person paid attention, if you watched at all, there was something there to understand about what it is to be a man. Girls, as often as boys, instinctively drew in closer. The brilliant gal from Montana who walked Seattle’s soggy streets in light boots and aspired to be a poet. Another, a young man, from whom once or twice a year there would come a late-nite telephone call to our house; Dad would not turn them down—and in time that fellow published searing poems about Vietnam—called The Long War Dead. Bob was sought out by more than one Seattle University student body president, because even they, sometimes, have trouble figuring it all out. He brought home the basketballer from LA streets who wasn’t sure what was coming for him beyond four years of good games. Bob listened. He had deep wells of kindness and of strength. And all these different sorts of good souls sensed that, if you watched Mr. Harmon there was often something to learn about what it is to be a man.

One of my earlier lessons came on a drizzly Seattle day—the professor would call that a redundancy—when I had been in front of a nice fire, at home. I was age 10 or 11. And the voice of the master of the house called me over to look out the window. “Why,” I wanted to know. There, slowly climbing the infamous Galer Street steep-walk, a woman, maybe in her thirties, was slowly making her way home, probably after a day at work, and carrying the world’s largest bags of groceries. “You should go help her up the hill,” said the man. This was disconcerting. I was dry—she was not. The groceries were all hers; we would never eat any. We’d never seen her before. And by the way, my dad wasn’t putting on HIS raincoat! Was his part in this plan tending the warm fire? He repeated quietly, ”You should go help her home—it’s the right thing to do.” When I got out there, the woman was baffled to see me. But we managed the groceries, and somewhere in that walk I figured out that it was intended for helping me, as much as the unknown woman. There was something there, for a mystified selfish boy, about what is needed to grow up.

A big part of Dad’s life was basketball with his faculty, student and family friends at SU gyms. And there is another whole set of little lessons about what it might be to be a man that my brother and cousins and I learned in these pick up games on the courts. For me there are a pair of special bookends, a set of basketball-with-Bob moments that box in a thousand more hours of games in his company. At the left, on this shelf of my memories, is a game when I was 16, on an outdoor basketball court in a park in Belgium. Our teenage opponents were eager but they lost quickly. After we walked away I said something exuberant and cocky about our little victory, and I was met fast with a reproof. My father said I might consider that boys didn’t grow up playing hoops in Belgium. And I might not like the results so much if the game had been soccer. His words weren’t nasty—just wise and exact.

The other game--that right bookend of my basketball memories—was 30 years later in our university’s new gym —the Connolly—and by then he was old. It was nearly the reverse of the experience with our European pals. We vaguely knew the two young men playing against us from our neighborhood on Capitol Hill. They knew we were aged out of the game, and I imagined I saw contempt showing. This two-on-two went hot and heavy for a while, and then I stepped to the side and asked a quiet word of my Team Captain. Probably very inappropriately, I said the cocky kids must lose this one. I have forgotten Dad’s reply, or if he made one, but there was a look of understanding in his eye. We went to it and Professor Bob really schooled those kids, and we won, making a memory for a gym rat like me who could never make the real teams. But somewhere in that is meaning, in two ways: Even in late age, Bob Harmon had deep reserves—in many things. And the other: my old man always had my back. He never, ever failed his kids. There’s a lot there about what it means to be a man.

That was our last game together. He taught history to many of the Chieftains over the years—the real players—but even more treasured—friends for a lifetime—were his earliest crowd of pick-up ball teammates: Joe Betz, Brian Ducey, Clint Hattrup… I mentioned our mathematician friend Andre Yandl to him, just now, January 15th , and he smiled a little and said “He was a terrific passer.” A ball passer is the kind of fellow that helps people, and that was Bob’s sort of person. The day our guy turned 70 years old he was a visiting professor at Hillsdale College, and he went down to the gym and shot around. He loved the camaraderie and the sport of basketball without allowing himself hoop dreams.

Sometimes he would halt our pick-up games – stop the action – to make some instructive point, or re-run the last play. New people were surprised by the intervention. But after all, this was Robert…and it is the master teacher that most people will remember. In the classroom it was an understated style, with quality all the way through. After a tour at St. Martin’s in Olympia, his home, he brought his abilities to Seattle University and served it for half a century. Many of those years were contemporaneous with Virginia’s own service – to Fr. McGoldrick, and at the Registrar’s Office.

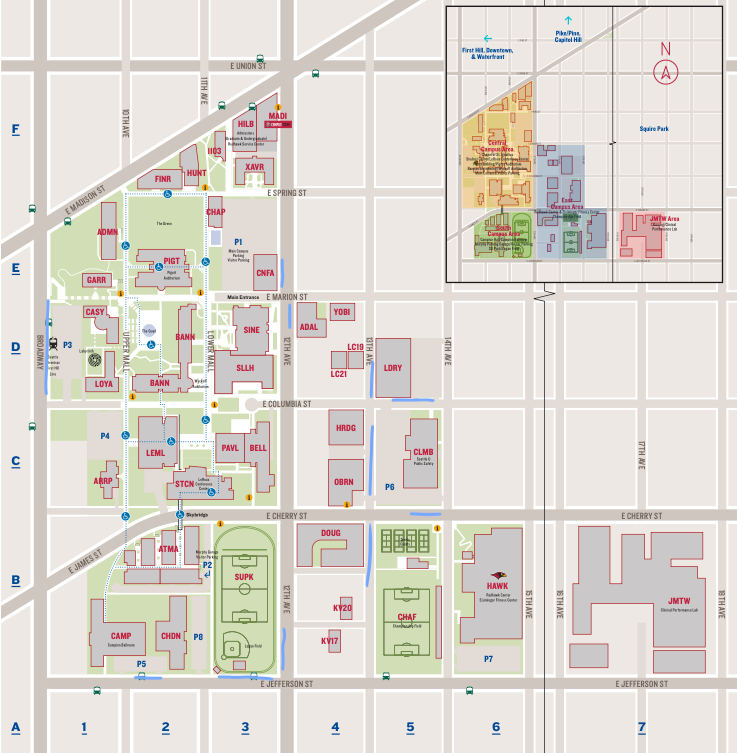

With each new quarter, the young in general studies waited, curious, in the 3rd and 4th and 5th rows across those long classrooms in Lemieux Hall, anticipating their first look at this representative of the History Department. A few weeks later, some of those would wait again, outside his office, in Xavier Hall, and later Marion Hall, to find out why the first exam had been inked over so harshly. There’s no forgetting my first “C” from Prof. Harmon, I can tell you. But a lot of those surprised undergrads became budding fans, and more focused. And some became history majors.

He tutored students in his office. He taught one or two from the basketball team the lineage of Roman emperors or English kings between free throws in the gym. He lectured for the ROTC. He gave a conceptual going-over to threes and twos standing in his kitchen while kneading dough for the next platter of Parker House rolls. “Sir Robert’s Open University” was always in session.

There was the Honors Program, begun by the creative, forceful. Tom O’Brien, S.J. Prof. Harmon gave decades to the Honors Program, and there’s a scholarship fund named for these two within the College of Arts and Sciences. Honors graduates start with names such as Ann Huetter (Johnson), Patricia Wand, Larry Brouse…and the line runs strong down thru Tim and Pat Brown from Capitol Hill. The worthy graduates are all out there now, in homes and offices all along life’s highways, and they are well. He taught a couple of generations, so then he got to teach a few of their children as well.

He offered a war and peace course, at Evergreen College, apart from classes at Seattle U. In these, there might be a few Vietnam vets sitting near a few of the wide-eyed who knew little of war, or who wondered frankly why anyone would ever go to war. They all learned—about political purpose, just war theory, military strategy, and about evil, about the wreckage it leaves. They’d read a little of the anti-war poetry of Wilfred Owen, and the rhyming story set in Flanders Fields by Canada’s soldier-poet of the Western Front, John McCrea. They’d learn about Dad’s anti-Nazi heroes such as Dietrich Bonheoffer, or the White Rose student cell. The Pattons and the Eisenhowers certainly came alive.

Private Harmon always praised the noncommissioned officers in the army he had known—for the instruction they gave, the moral force they had, and the lives they saved. Professor Harmon’s prides included those he taught in R. O. T. C. at Seattle University. A wish, mentioned several times in recent years, was to gift them a box of his books on war with the reminder that they are smart, but they must also read.

The Prof. was one to throw out old teaching notes in favor of a fresh breeze. There were always new themes, or a new course, or a special invited speaker. Some of his surprises came from outside: A low key, articulate officer talked through a remarkable 7 tours inside low intensity conflict in Northern Ireland. For years, Dad hosted Malcolm Miller, the Englishman with a magic lantern who showed you the whole world in the windows of Chartres Cathedral. This Robert-and-Malcolm partnership filled a campus auditorium every year.

Dad would team-teach. He ran courses with his great friend, historian Al Mann, surely one of the best minds to grace Seattle University in the decades running up to 2000. Dad saw him at a distance on the mall one day and he said to me, “Ah, there goes Albertus Magnus,” in reference to the 13th c. Aristotelian. A few years ago he taught with his former student, Joe Guppy, who is a son of Seattle University in at least two ways. I recall the classroom in the Bannan building, jammed with graduate students and their professors. The new M.A. in Counseling and Psychology, Joseph, explained the theory of Emmanuel Levinas about “the other;” then the veteran of 1944/45 talked through what it could mean for him in understanding his war with German opponents of those days. He was glad, after the war, with how he came to see “the other” in the German population. At his youngest as a father, Bob had often refused to walk us boys back over his bloody ground; he would politely evade our questions. That changed, as many of you know; that changed after aging; he became voluble. So, Professor Guppy had one taut classroom as Private Harmon made a kind of controlled fall back through layers of thought and emotion to where he could see again his fears, and tell new students about them. I believe that may have been his last class taught at Seattle University.

One or two of you may know if Bob often confessed, formally in the church—I don’t know. We all do know how very often he was at mass, and how humble he could be. And another prize among those poems in that little blue collection was “The Fool’s Prayer” by Edward Sill. My cousin Rodney Harmon and some other Honors Program students once heard this recited at dusk at Bob and Gina’s cabin on Hood Canal. The ten stanzas of Sill capture the deepest humility. I think my father loved them for their attention to two of his guides through this world: Christianity, about which he was firm; and humility—including the modesty he thought fitting for the life of the mind. Do you remember, how he would say, in his classrooms, “I don’t know, but I should.” Or, “Well, we’ll have to suspend judgment on that.”

It is hard, now, for us to not feel selfish. At such a time, it is easy to slide south, obsessing on what is lost. To say ‘there was nothing like him, and now the world seems dark to me.’ But if there’s anything we know of Charles Robert, it’s that he would not countenance too much regret for too long…. He never was morose; self pity was beneath him. What good fortune we’ve had to know him. What a good reflection it is on you, that he wanted and kept your company! You’ve seen aspects or angles I was too young to understand. You’ve had your museum moments in one of a dozen Gina and Bob European tours of the 1950s through the

2000s. You heard that morning talk at “The Hearthstone” or at a university, by one of the only living “Monuments Men” of the Austrian salt caves of 1945. You kept going the bridge games, or the little coffee klatch of retired Seattle U. professors, which I got to see in action on a Saturday morning in 2017. You had that hour in formal tutorial, a paper conference, or just a coffee in the Chieftain, in which, suddenly, you understood something that had been bedeviling; a complicated thought line straightened; a pattern appeared; or a cause became visible.

What a priceless quality that is—the mentor who gives the time, and has the ability and the personality—to....let… “insight”.... come....to…another. For all who became life-long “general studies majors” under Professor Harmon we could give a twist to a phrase by one of his favorite historical figures, T. E. Lawrence, and say that for us, “Even if nine-tenths of the hours over our books may be difficult, or banal, the tenth is like the flash of the Kingfisher over the pool.”

In a gathering so broad as the Seattle University community, there are few limits to the wonderful moments had with this fine man. For all who knew him at length, those memories are layered down thickly for you, year upon year, like leaves of nature. Preserve them! And re-tell your stories.

How lucky you are.

How lucky the Harmons are to have their memories that smile through the rains of Seattle.

- Chris, kid 2 of 4

The following announcement was shared with the SU community on Jan. 26:

Professor Emeritus Charles Robert (Bob) Harmon, whose outsized impact on Seattle University spanned several decades, died Jan. 22 at the age of 97.

Bob began a lifelong relationship with SU when he enrolled as a student in the late 1940s. Graduating in 1950, he returned three years later to teach history. Over 40 years as a faculty member, Bob held a number of key positions with the university. He directed the evening school program and was a principal faculty member in the university’s Honors Program. Adored by students and colleagues alike, he was named the university’s Distinguished Teacher of the Year in 1969 and received a teaching award from the Alumni Association in 1993.

To the discipline of history Bob brought a distinctively personal, firsthand perspective. Serving as a rifleman in General George Patton’s Third Army, he participated in a number of pivotal moments during World War II, including the surrender of Weimar and liberation of a concentration camp. Through numerous lectures and in more intimate settings, Bob was always generous in sharing his personal stories, while artfully drawing upon history to help make sense of the issues of the day. He had a special affinity for the university’s ROTC officers and will be donating some of his books to the program.

Bob’s impact extended well beyond the classroom and in both formal capacities—such as serving as advisor to the Hawaiian Club and organizing trips to Europe—and more informally, Bob contributed mightily to the life of the university and always put SU’s students first.

After his official retirement from SU in 1993, Bob remained close to the university and committed to its ongoing success. He continued to teach (through 2013) and serve his alma mater. His intellect, while considerable, never kept him from relating to others in a down-to-earth way—his “shop talks,” in which he shared history lessons with Facilities colleagues in their breakroom over lunch, being one example.

Bob and his wife Virginia (Gina) met while students at Seattle U, and Gina would serve as assistant registrar for four decades. Their contributions have gone a long way in making SU the university that it is. Let us keep Gina and the Harmon family in our prayers.

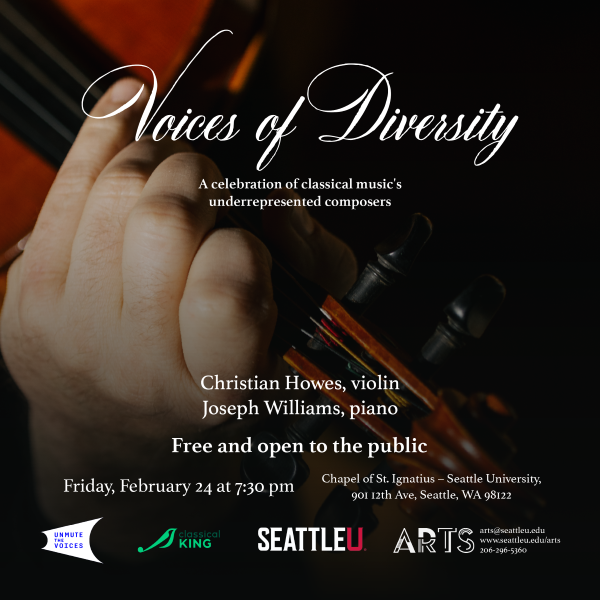

A funeral will be celebrated at 10 a.m. on Monday, Jan. 30 at the Chapel of St. Ignatius.

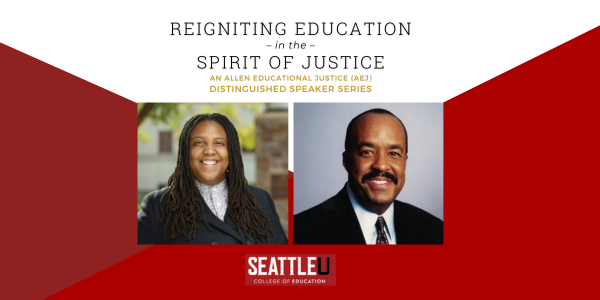

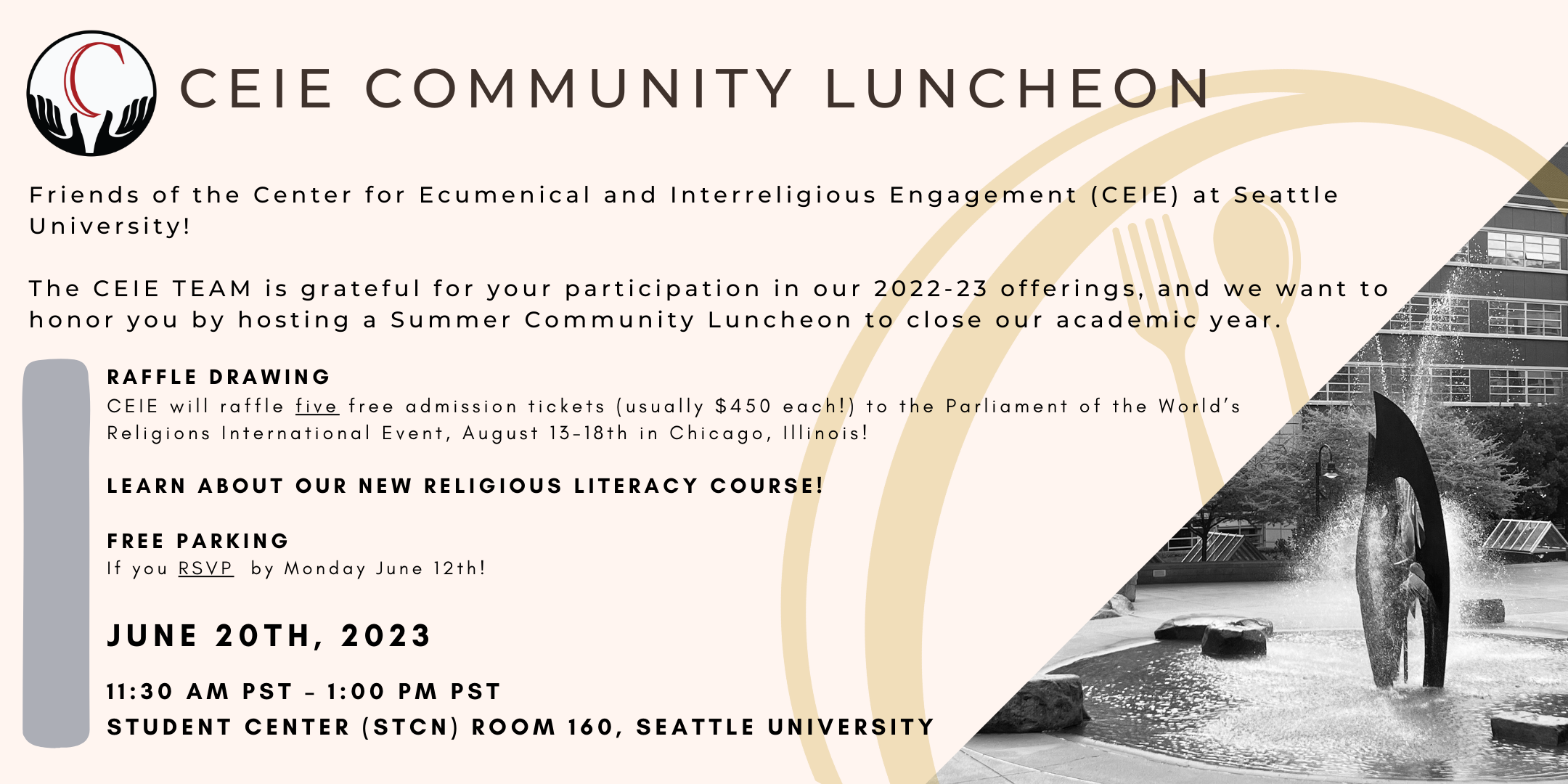

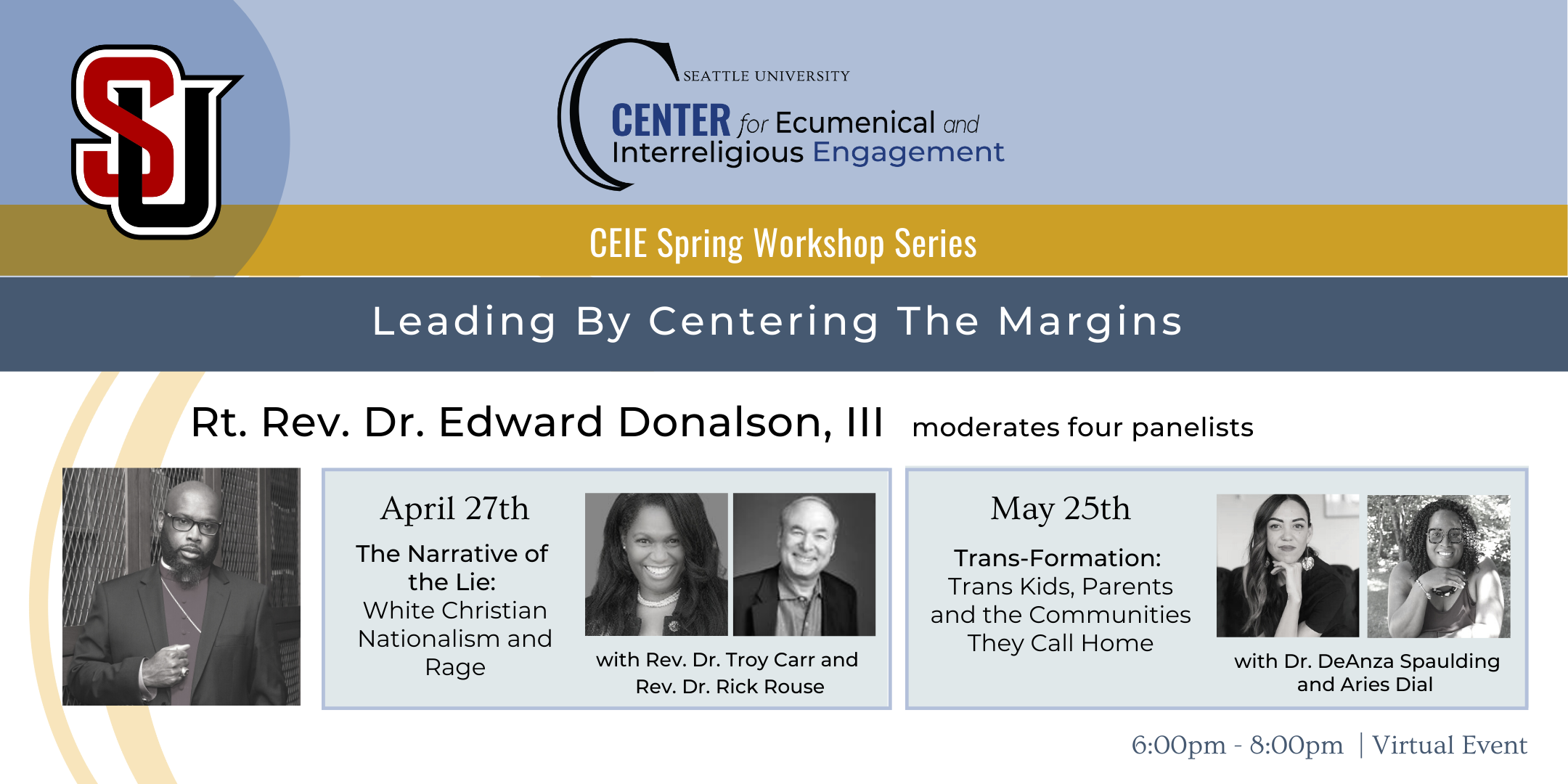

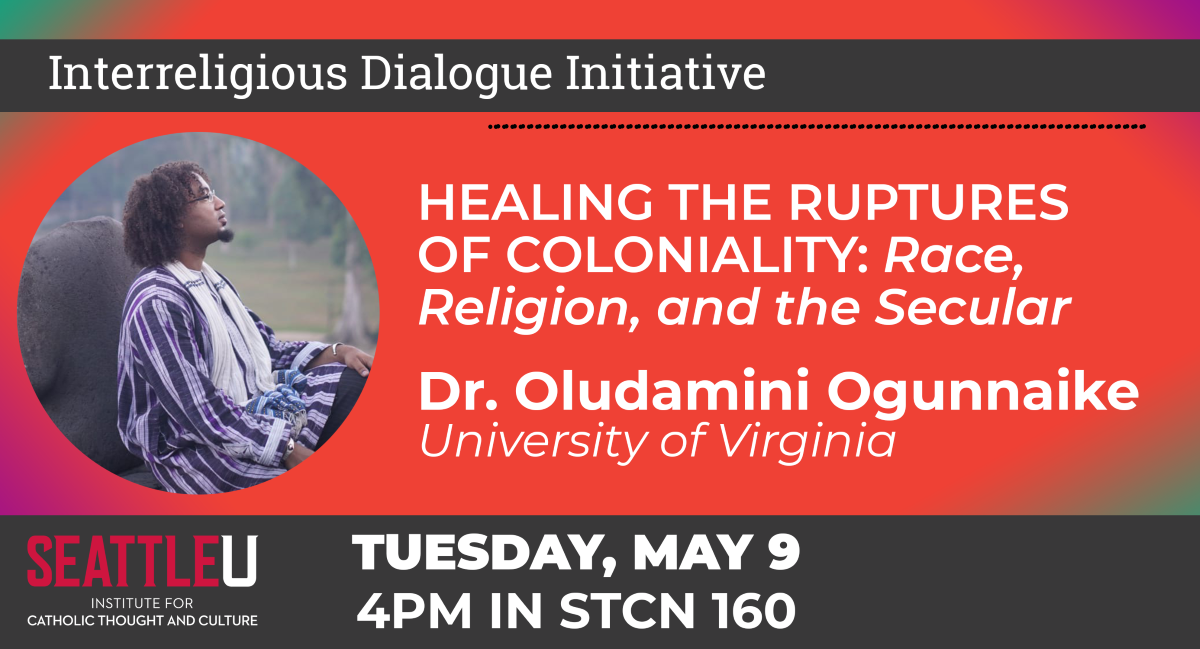

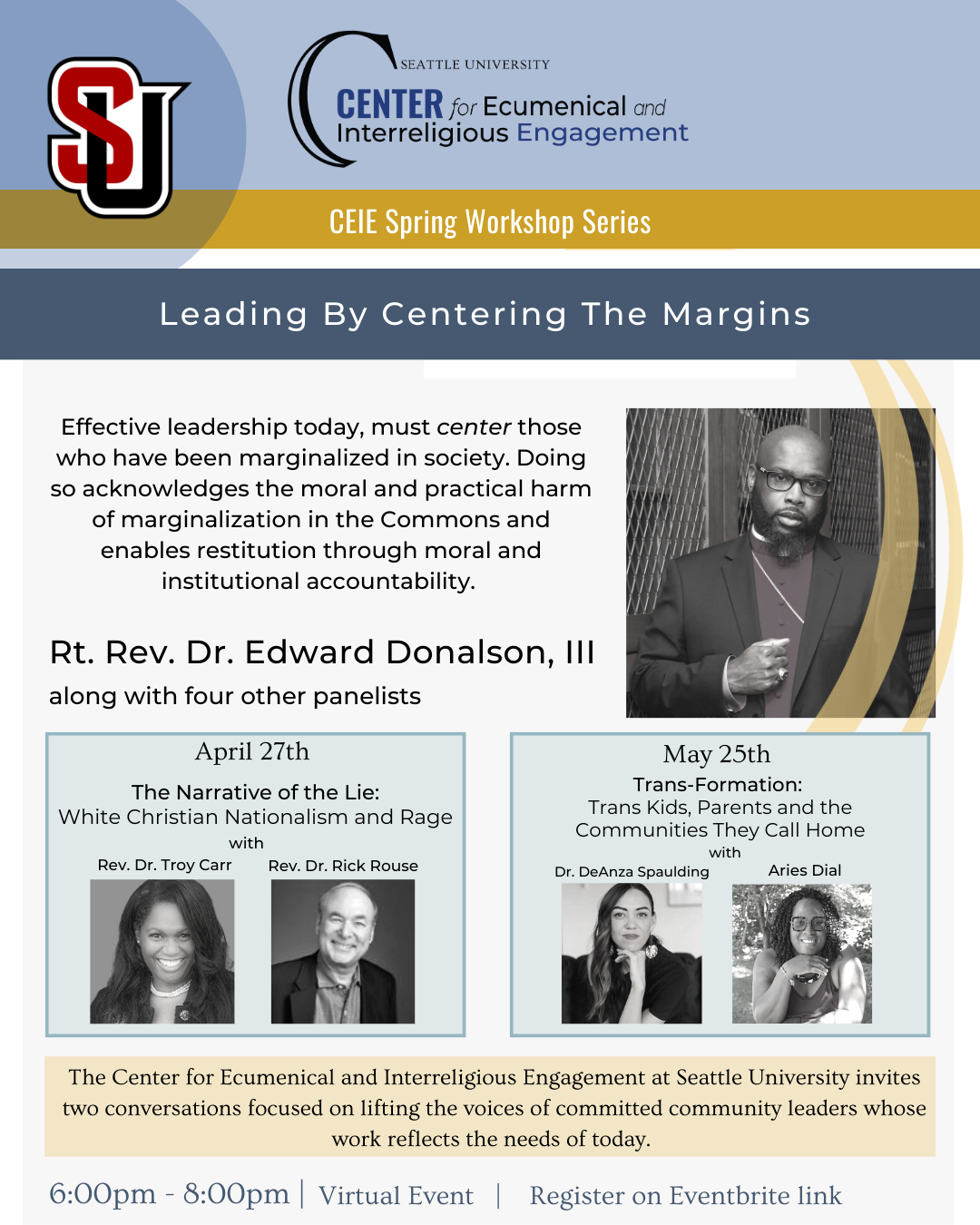

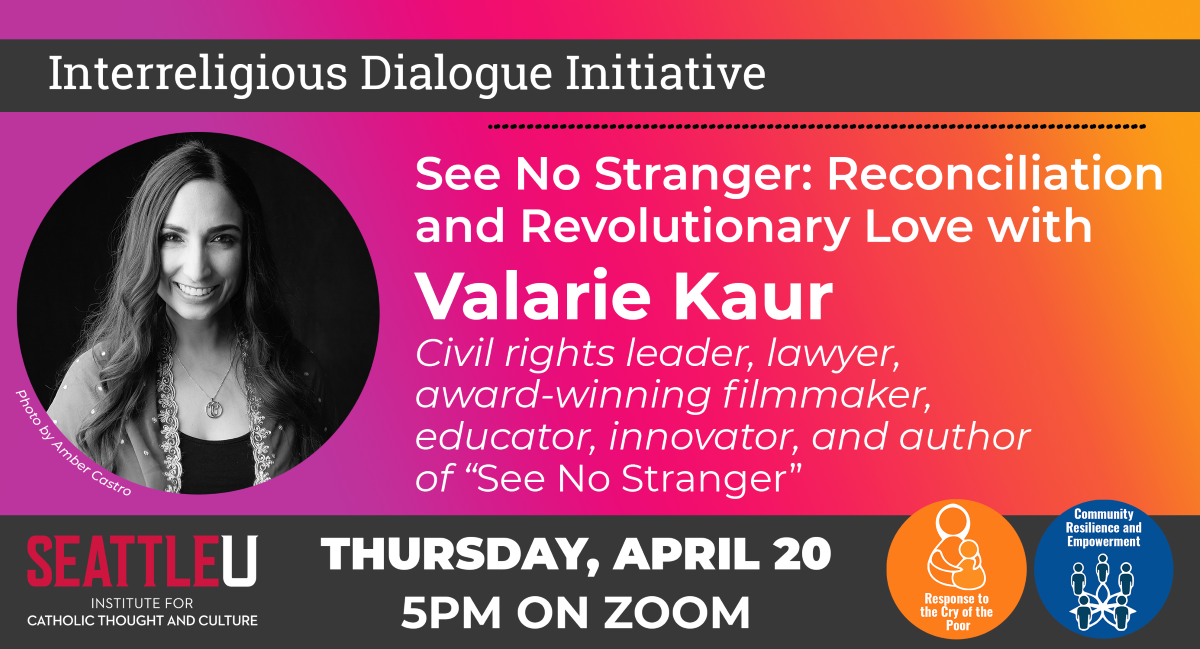

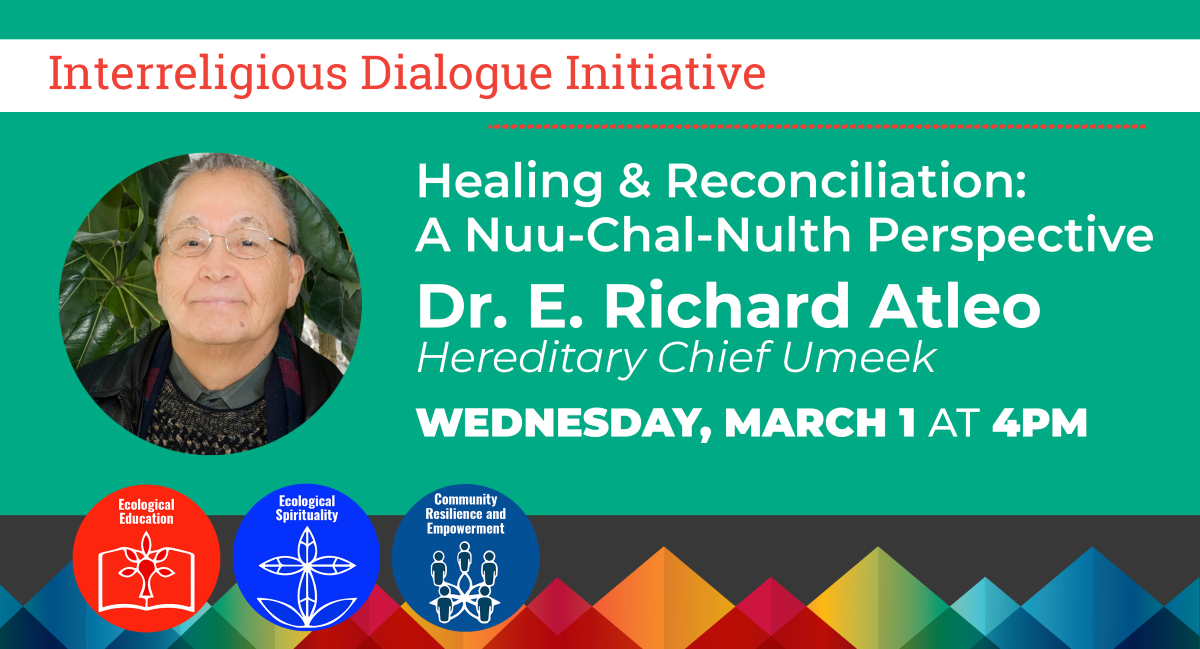

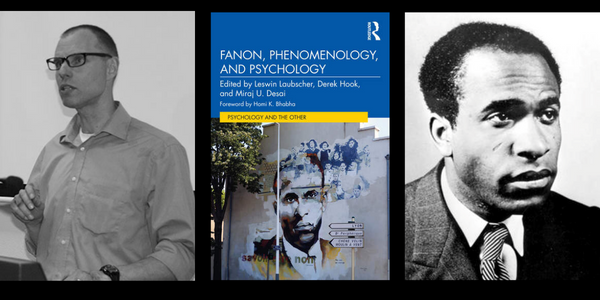

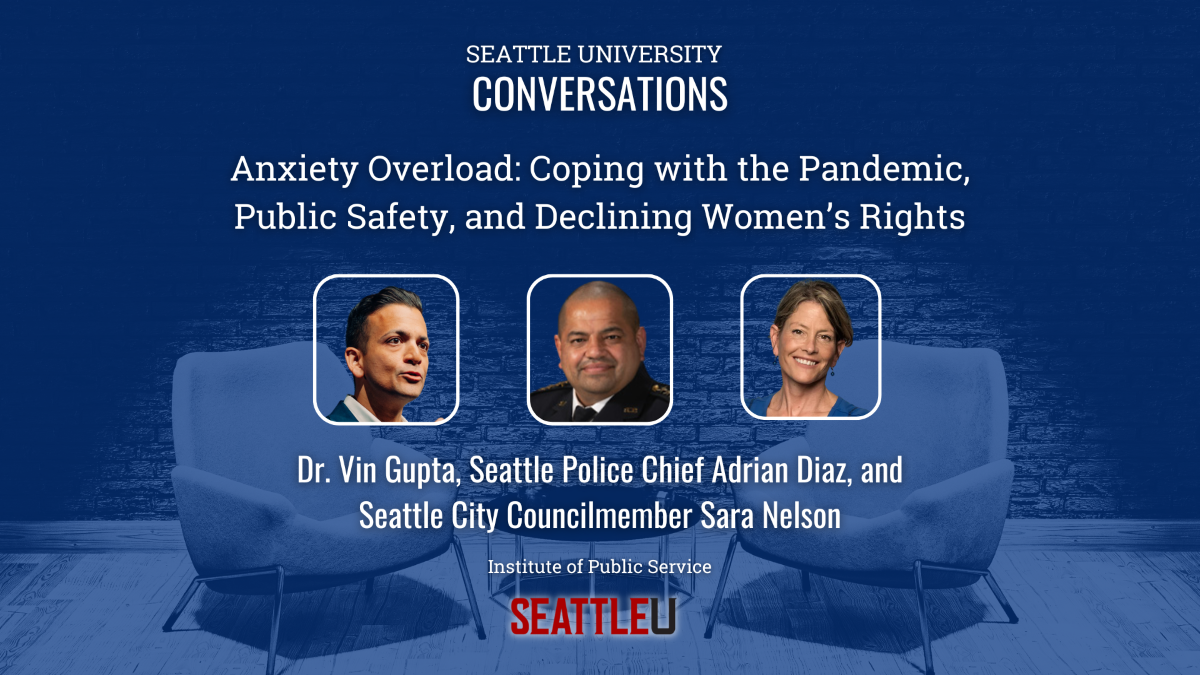

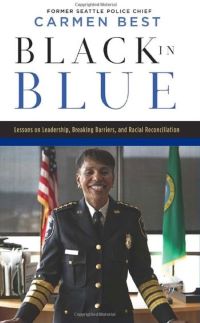

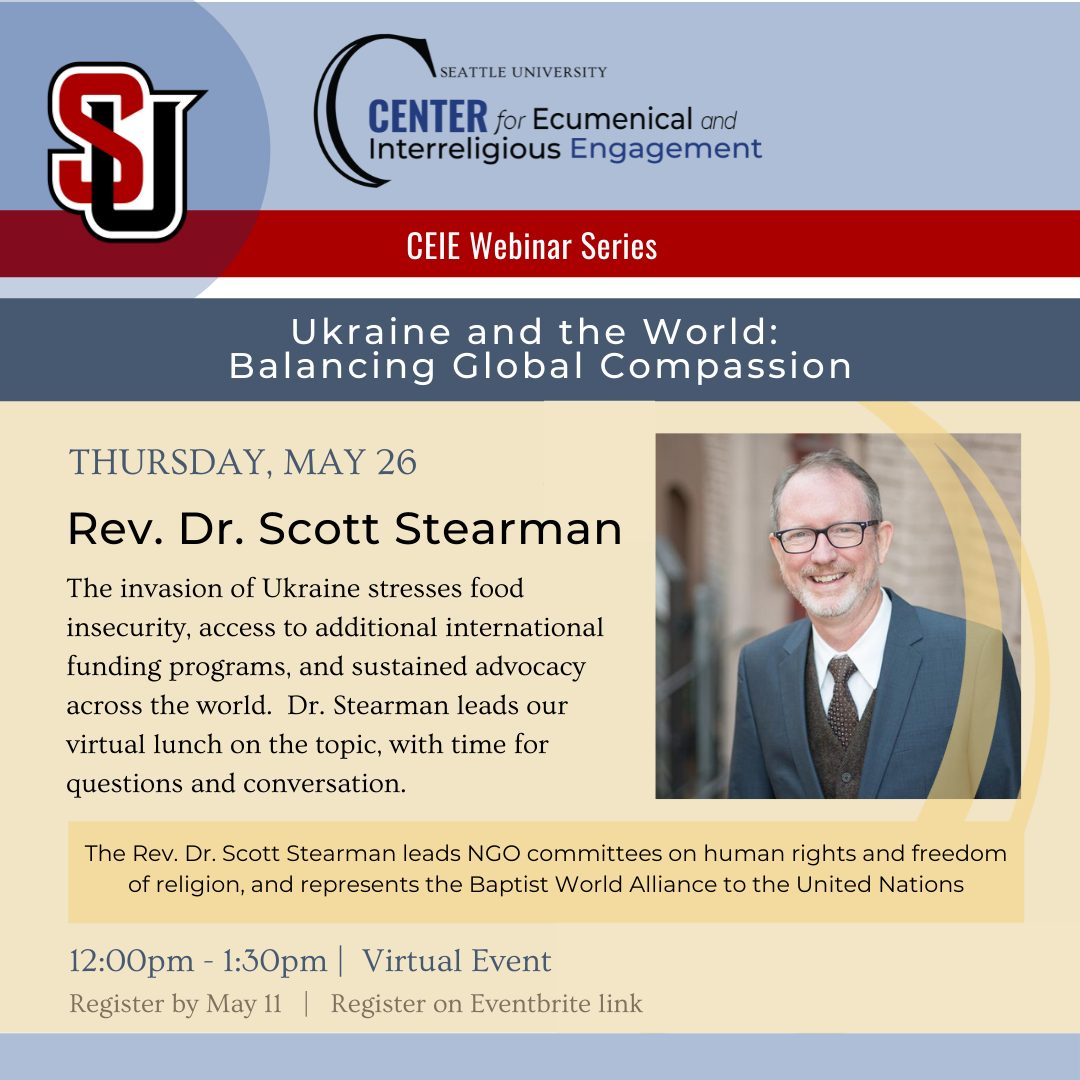

Center for Ecumenical and Interreligious Engagement Director Dr. Michael Reid Trice speaks with Dr. Eric Alterman, CUNY Distinguished Professor of English and Journalism at Brooklyn College, about the hypocrisy of modern America.

Center for Ecumenical and Interreligious Engagement Director Dr. Michael Reid Trice speaks with Dr. Eric Alterman, CUNY Distinguished Professor of English and Journalism at Brooklyn College, about the hypocrisy of modern America.

Tuesday, May 21, 4 p.m.

Tuesday, May 21, 4 p.m.

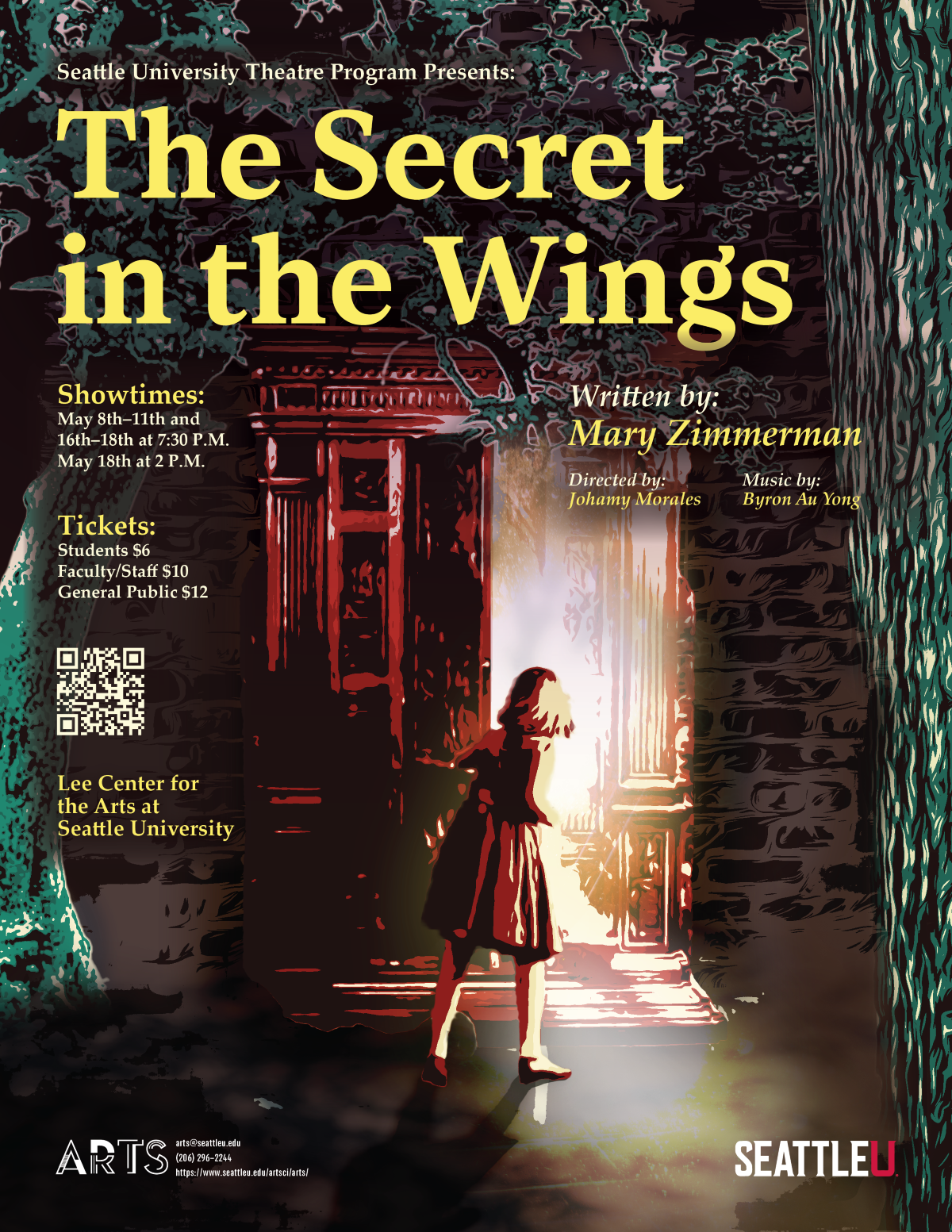

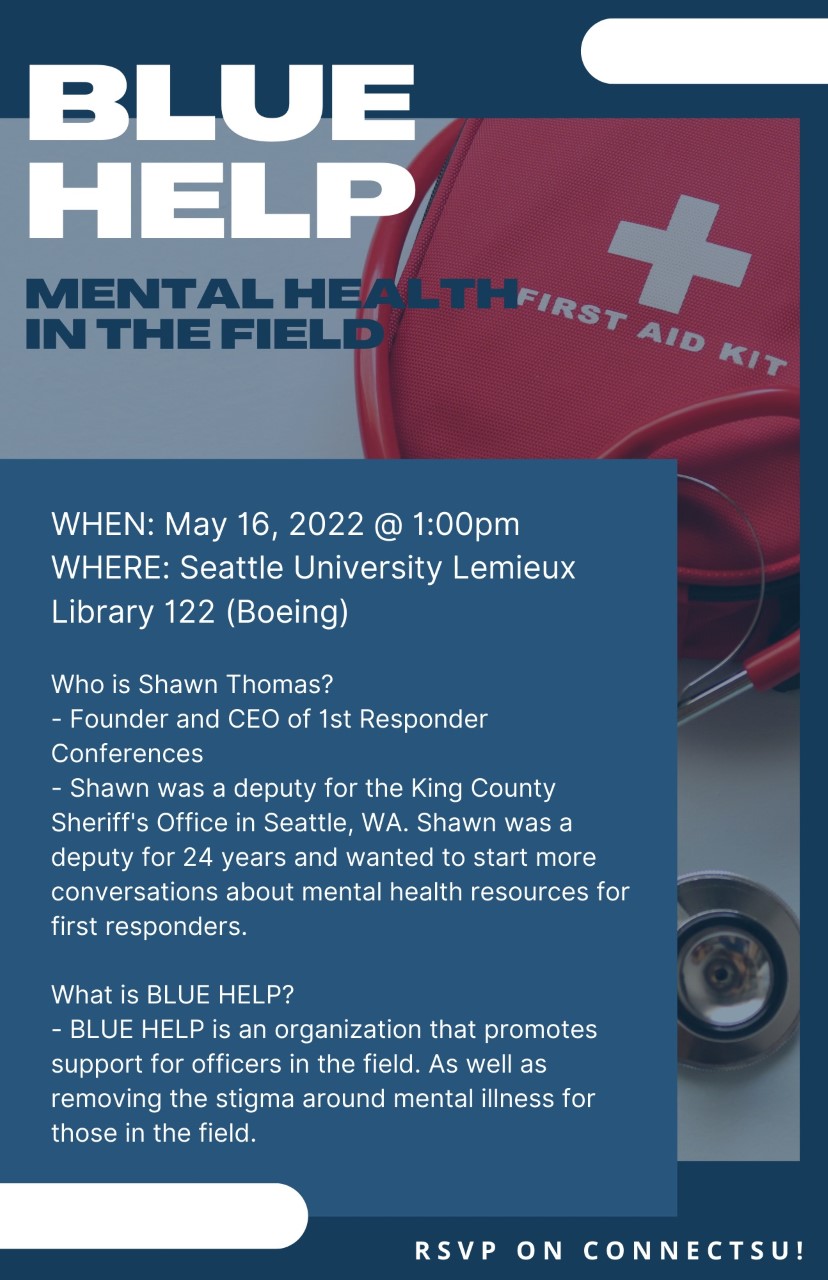

Thursday, May 16, 12:30 p.m.

Thursday, May 16, 12:30 p.m. Wednesday, May 15, 4–5:30 p.m.

Wednesday, May 15, 4–5:30 p.m. Tuesday, May 7, 11:45 a.m. – 2 p.m.

Tuesday, May 7, 11:45 a.m. – 2 p.m.

.png) Students: Learn to assess, maintain and work on your car or bike so they perform at their best:

Students: Learn to assess, maintain and work on your car or bike so they perform at their best:  Dear Campus Community,

Dear Campus Community, .png) Students: Send a free postcard anywhere in the world to a friend, family member or anyone who might enjoy getting some mail: May 13, noon–2 p.m., and May 14, noon–2 p.m. at the Lemieux Library Floor 2 Atrium (near the Byte Café). Learn more at

Students: Send a free postcard anywhere in the world to a friend, family member or anyone who might enjoy getting some mail: May 13, noon–2 p.m., and May 14, noon–2 p.m. at the Lemieux Library Floor 2 Atrium (near the Byte Café). Learn more at .png) Join in celebrating our students’ projects at the Student Research and Creativity Conference (SRCCon) on Friday, May 10, from noon to 4 p.m. in Lemieux Library (Floor 3). This is a great way for students to stand out on resumes and applications, taking their academic and professional work to the next level. Learn more at

Join in celebrating our students’ projects at the Student Research and Creativity Conference (SRCCon) on Friday, May 10, from noon to 4 p.m. in Lemieux Library (Floor 3). This is a great way for students to stand out on resumes and applications, taking their academic and professional work to the next level. Learn more at

Wednesday, May 1

Wednesday, May 1

Friday, May 24, 10:30 a.m. – noon

Friday, May 24, 10:30 a.m. – noon

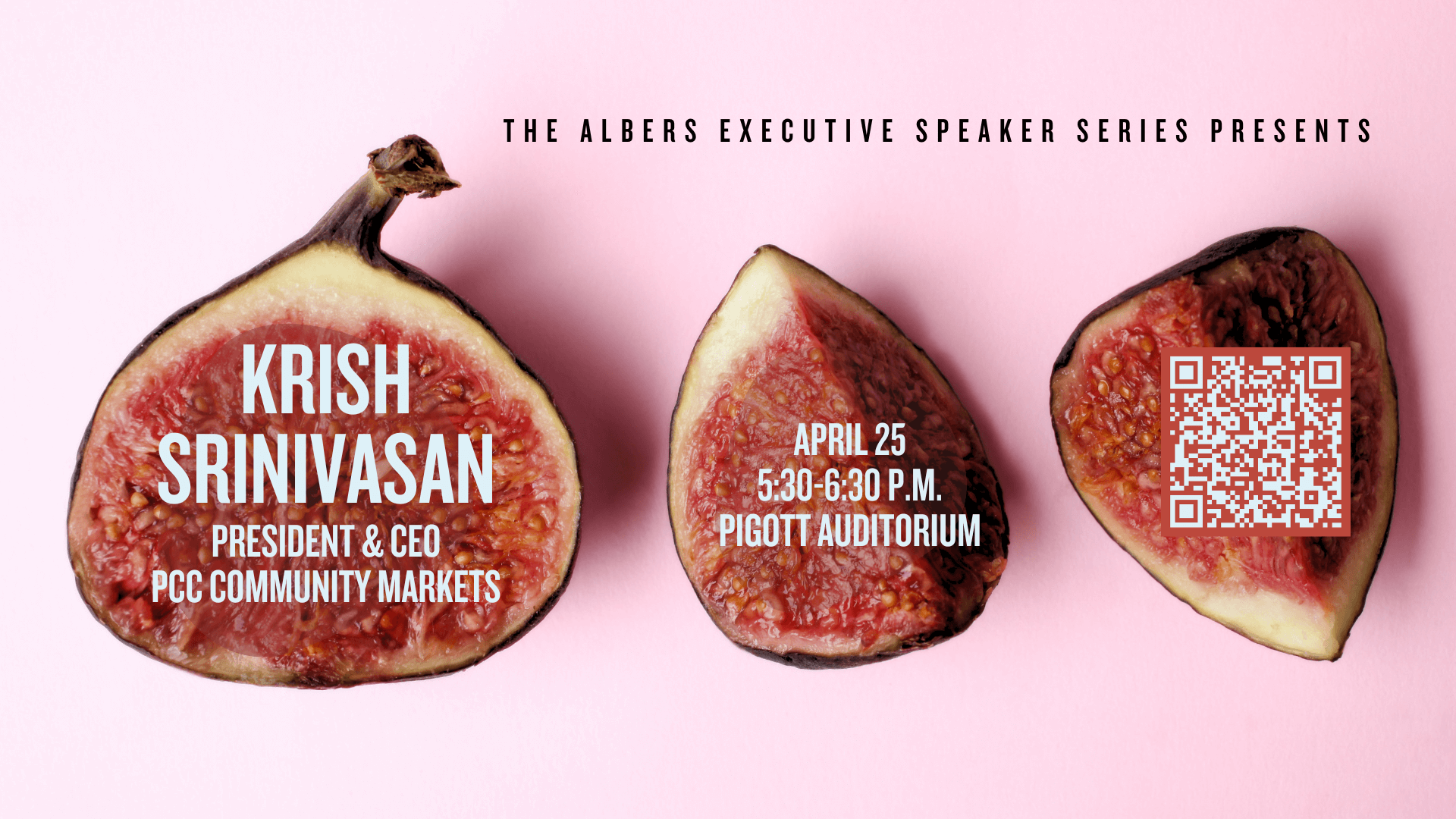

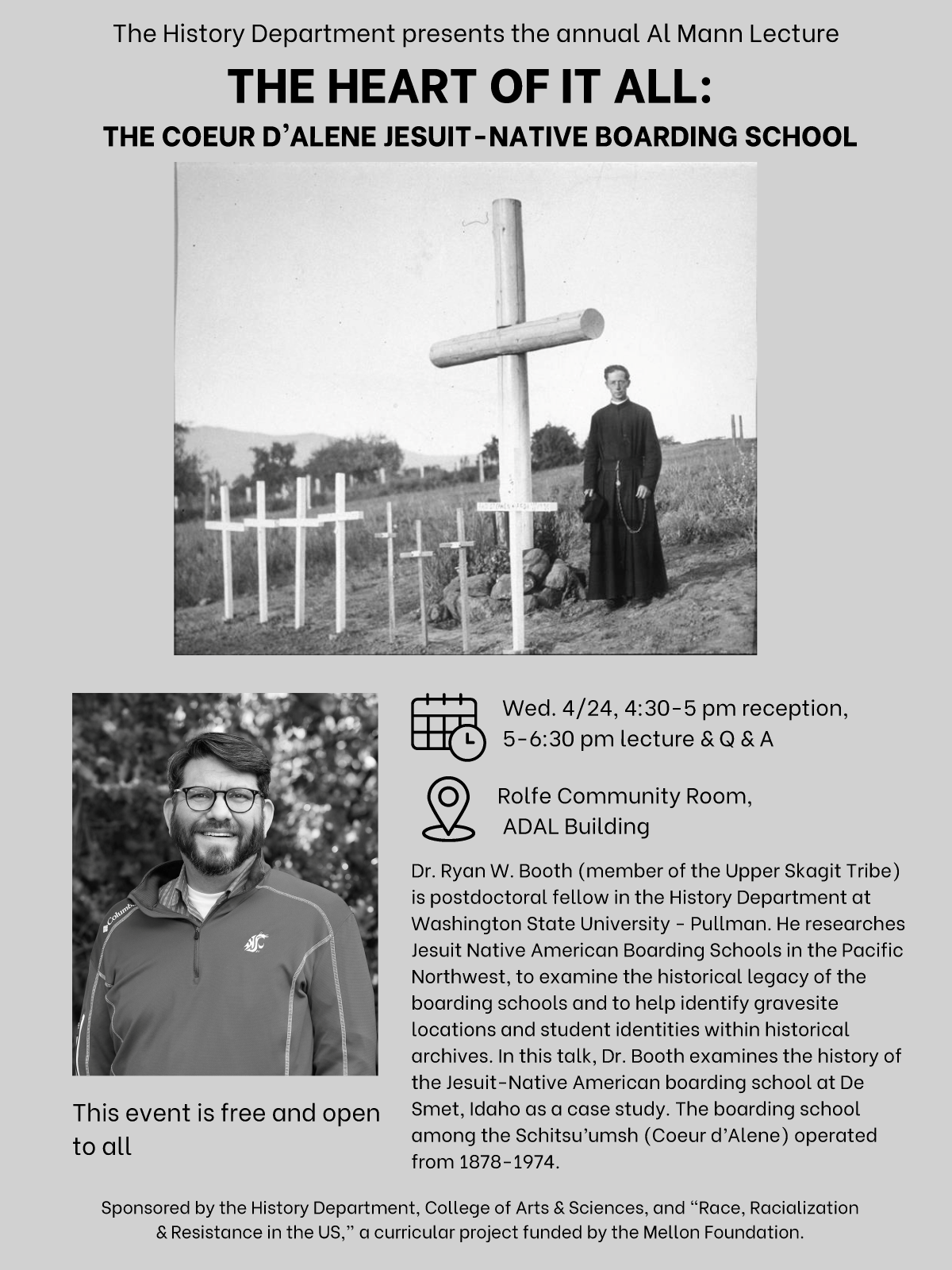

Thursday, April 25, 5:30–6:30 p.m.

Thursday, April 25, 5:30–6:30 p.m. Tuesday, April 30, 12:30–1:30 p.m.

Tuesday, April 30, 12:30–1:30 p.m. Thursday, April 25

Thursday, April 25

Friday, May 10, 9 a.m.–5 p.m.

Friday, May 10, 9 a.m.–5 p.m.

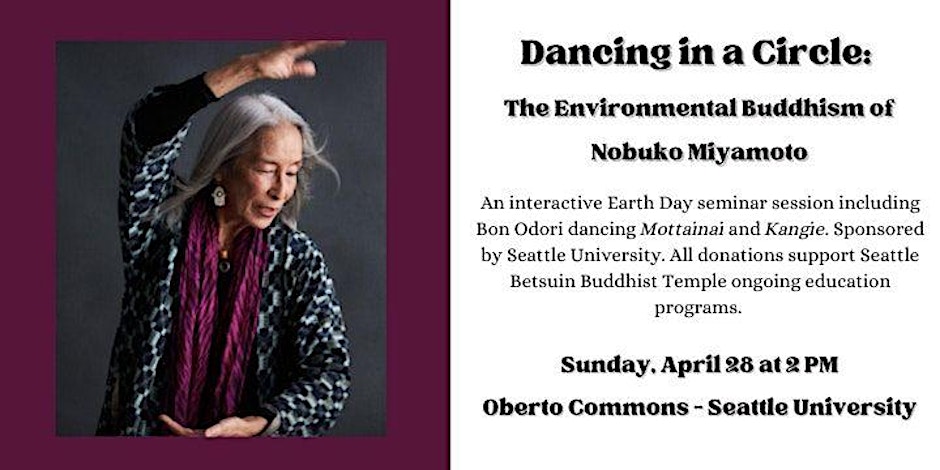

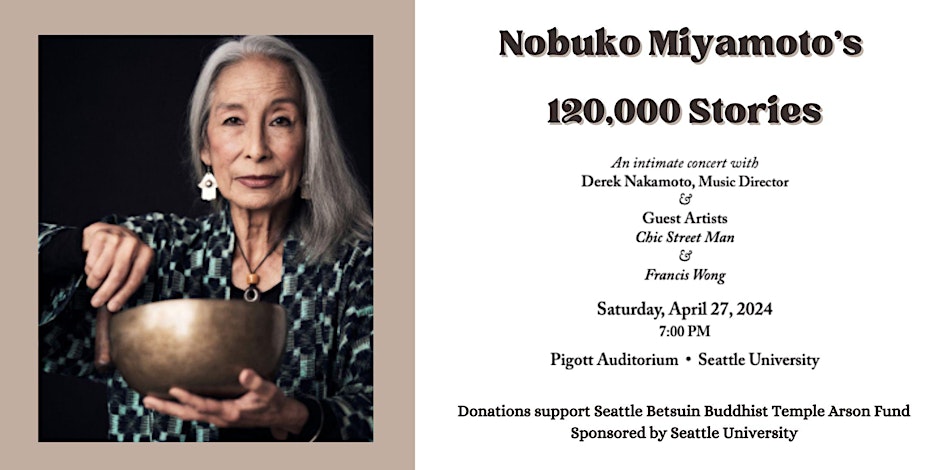

Saturday, April 27, 7 p.m.

Saturday, April 27, 7 p.m.

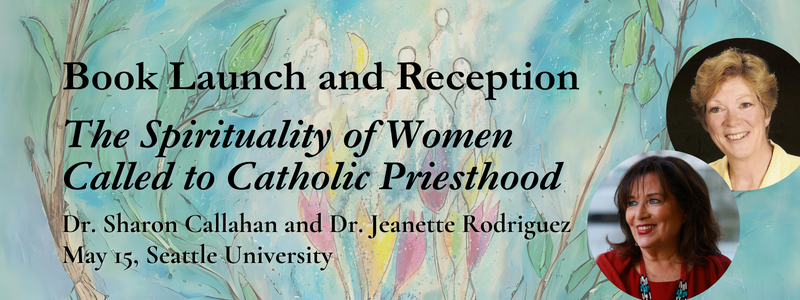

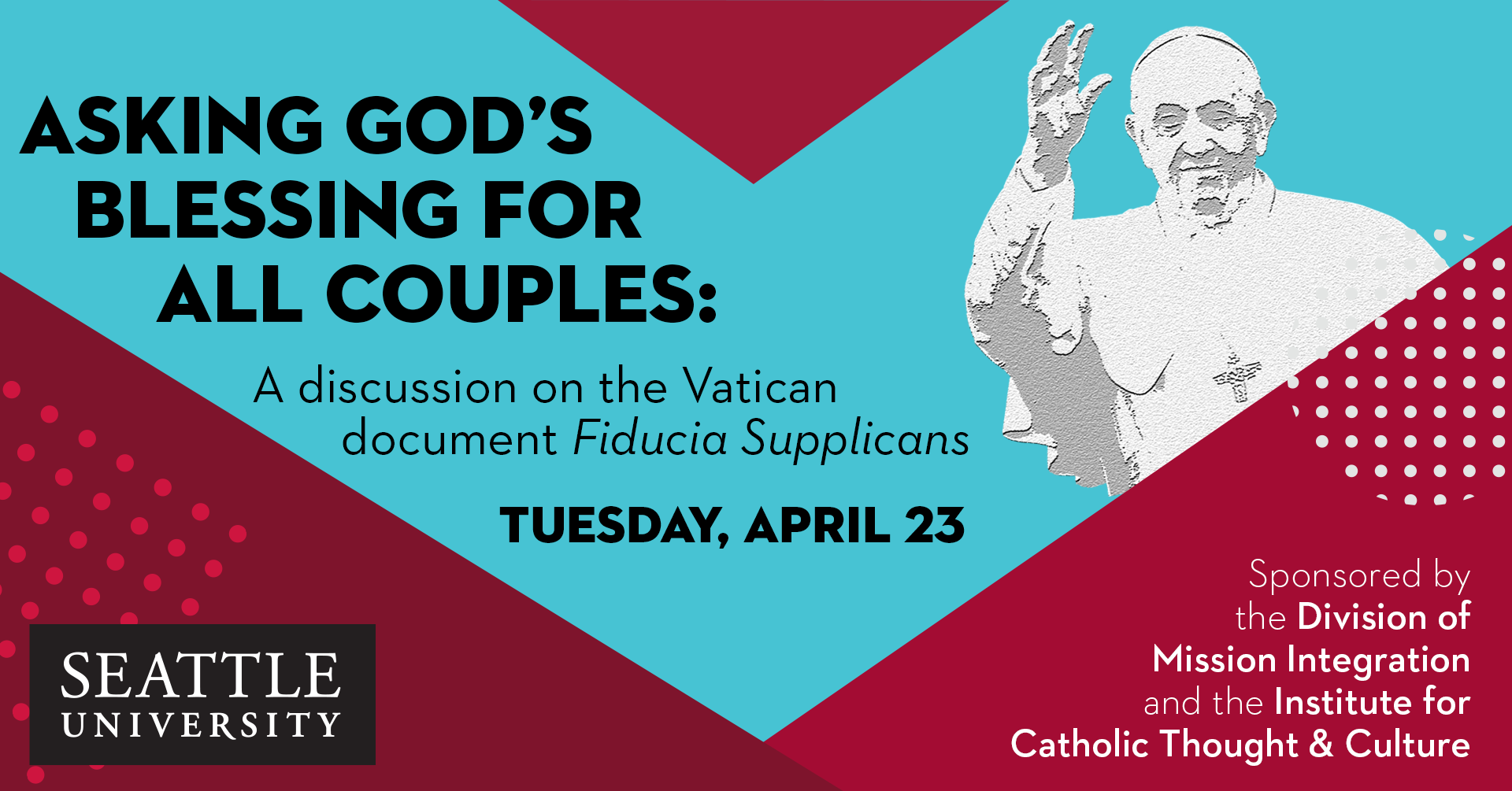

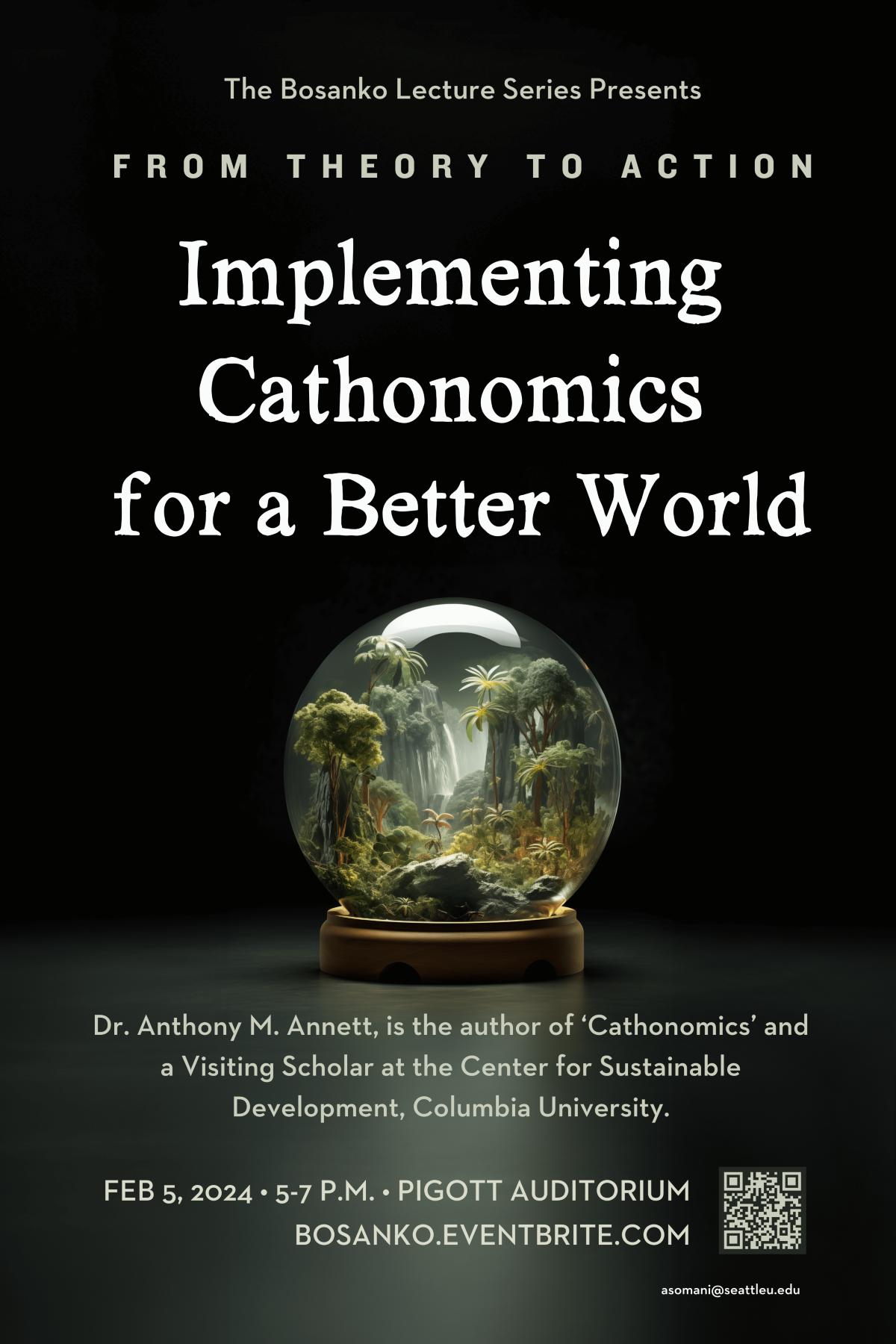

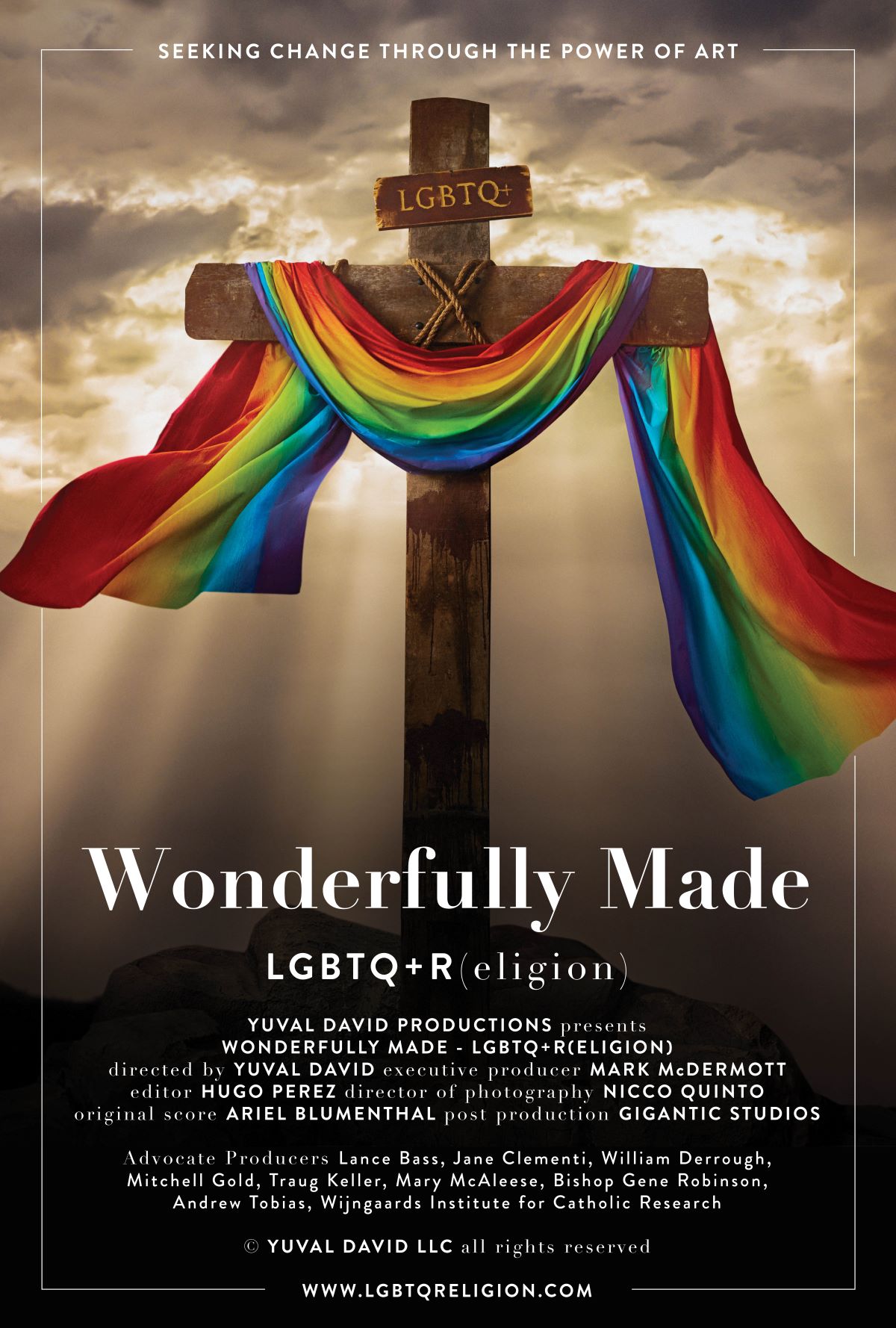

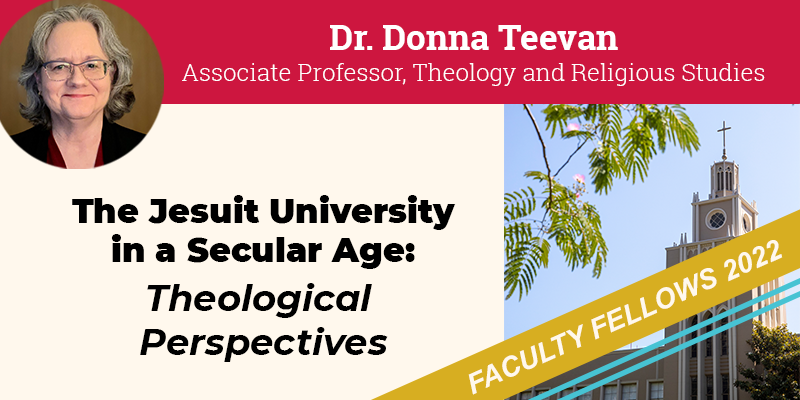

In December 2023, the Vatican shocked both the Catholic community and the world with the release of

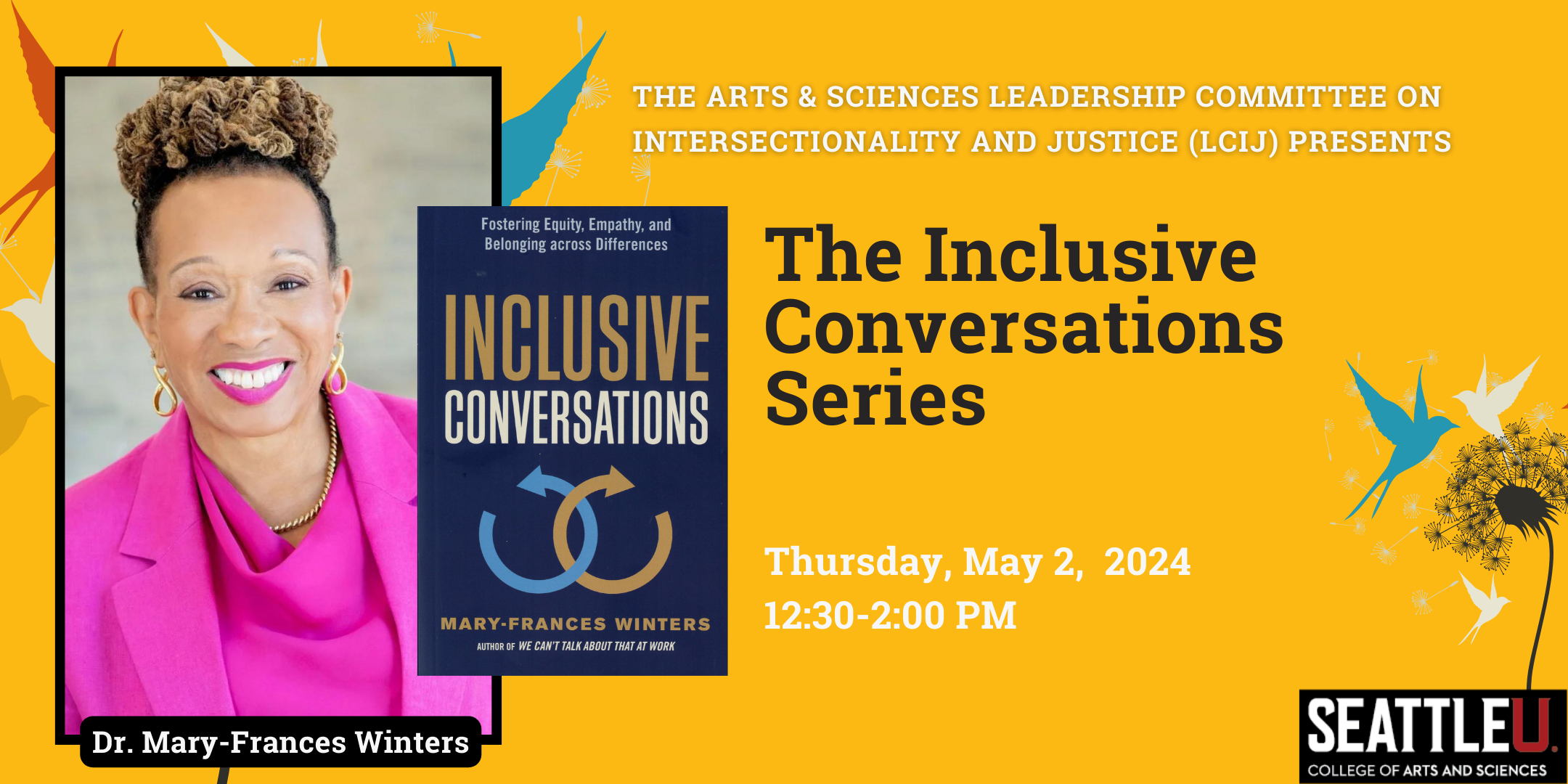

In December 2023, the Vatican shocked both the Catholic community and the world with the release of  Thursday, May 2, 12:30–2 p.m.

Thursday, May 2, 12:30–2 p.m.

Friday, April 12, 1–2:30 p.m.

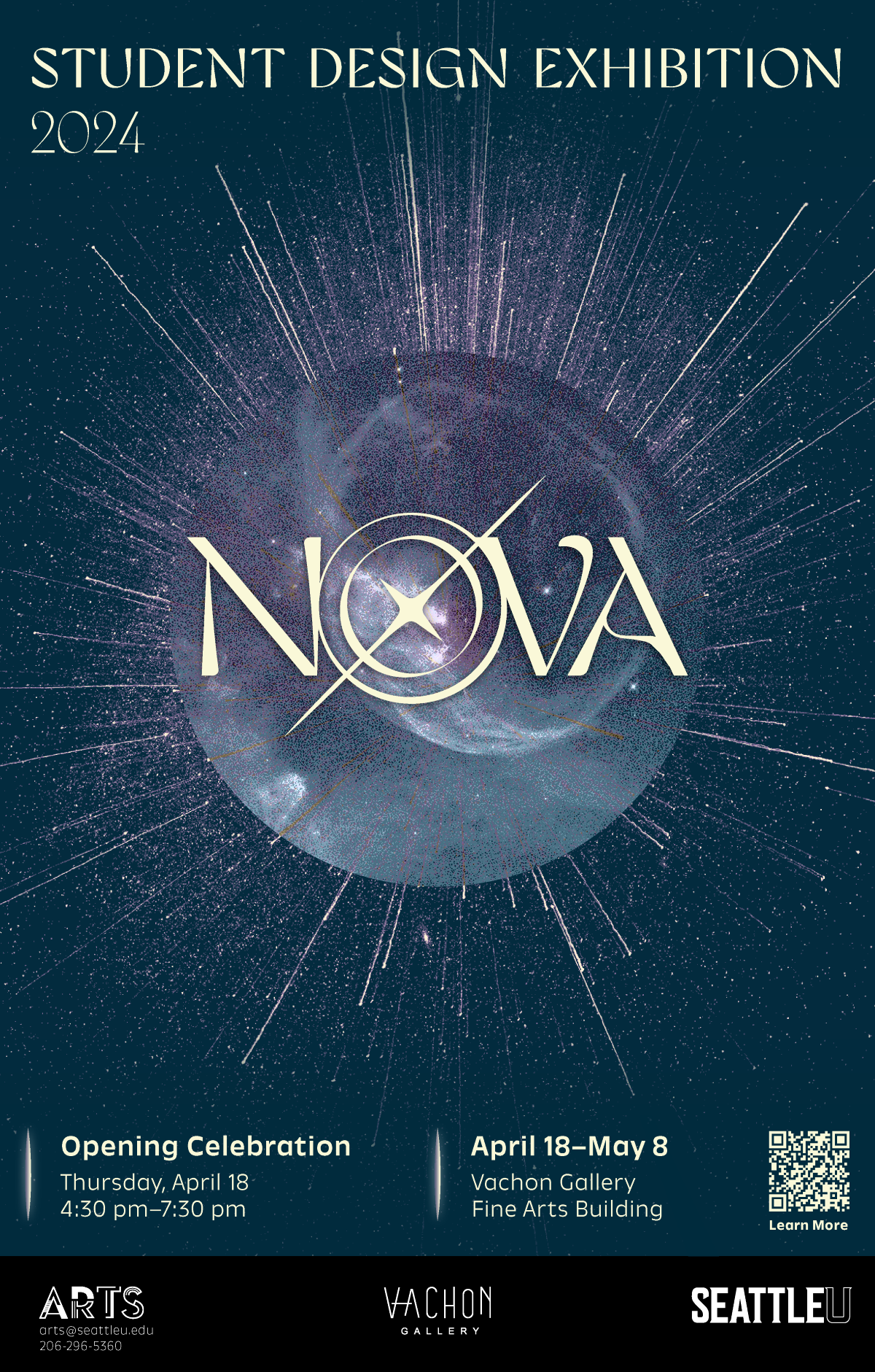

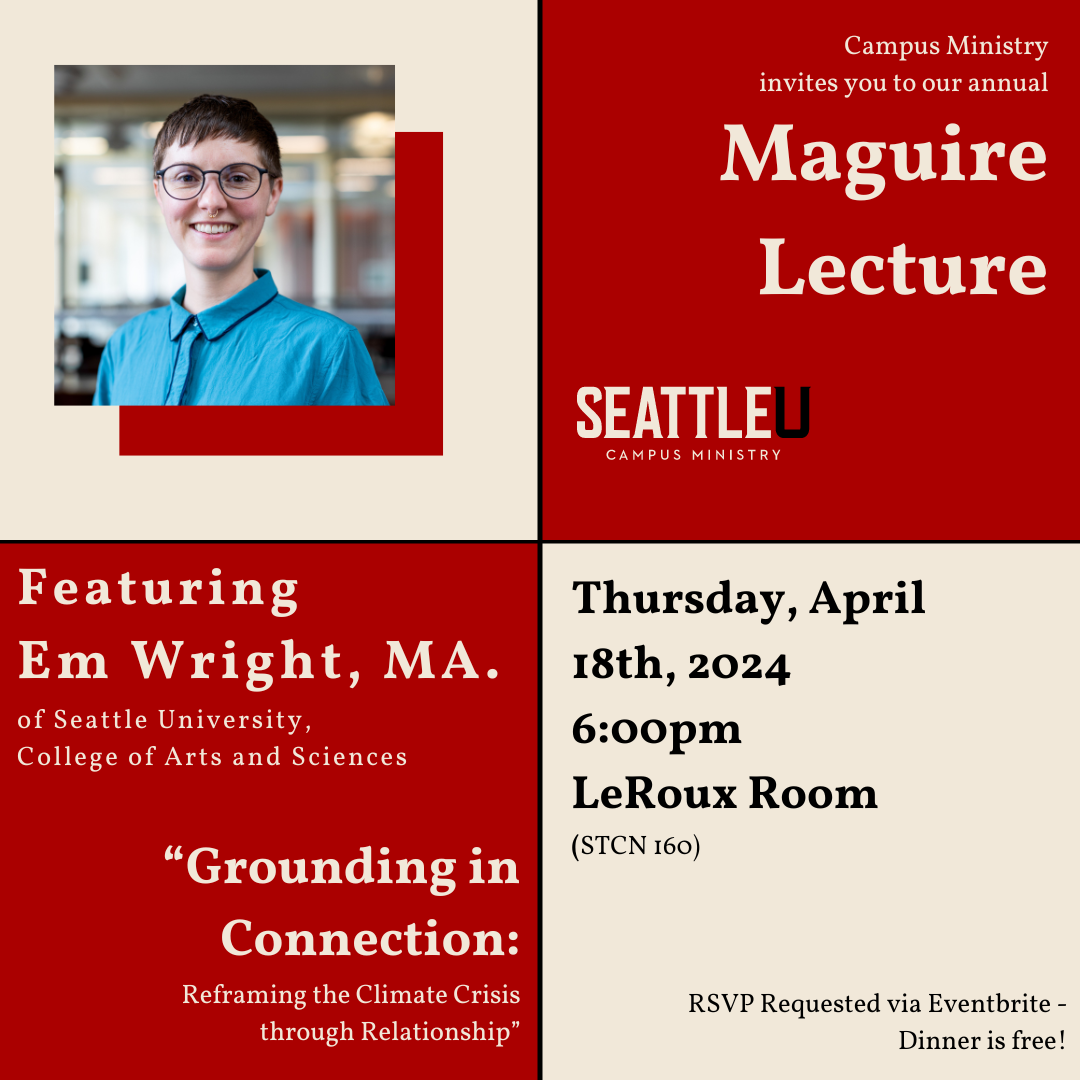

Friday, April 12, 1–2:30 p.m. Thursday, April 18, 6–8:30 p.m.

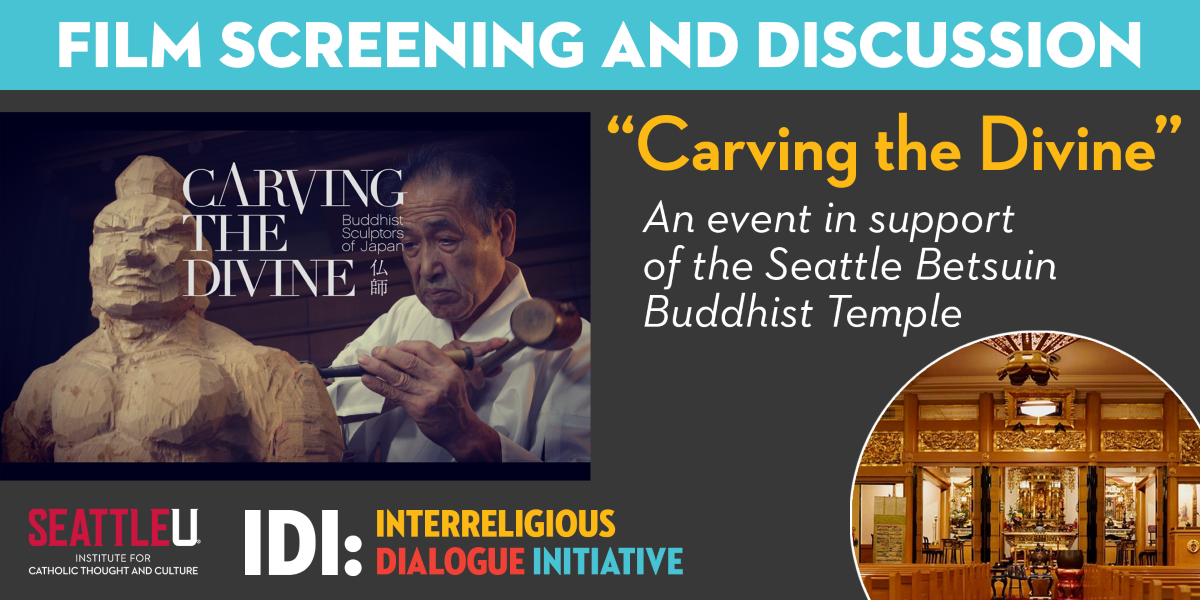

Thursday, April 18, 6–8:30 p.m.

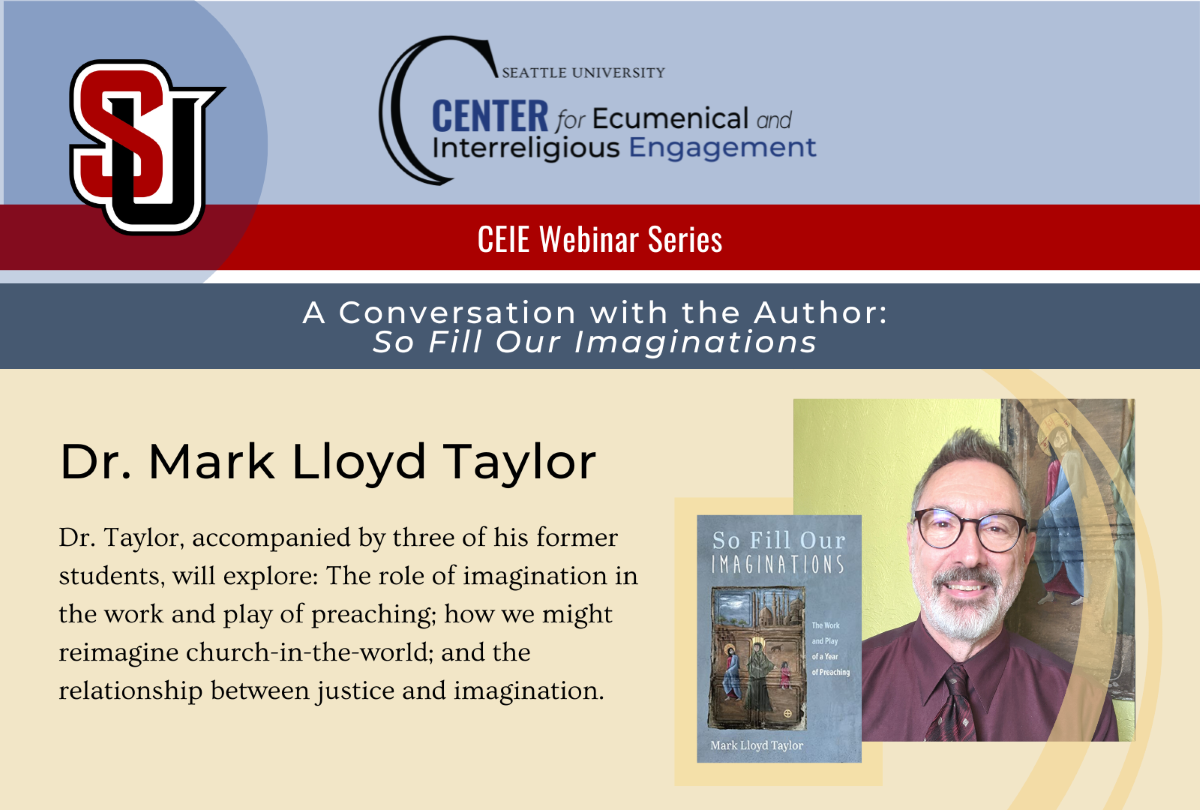

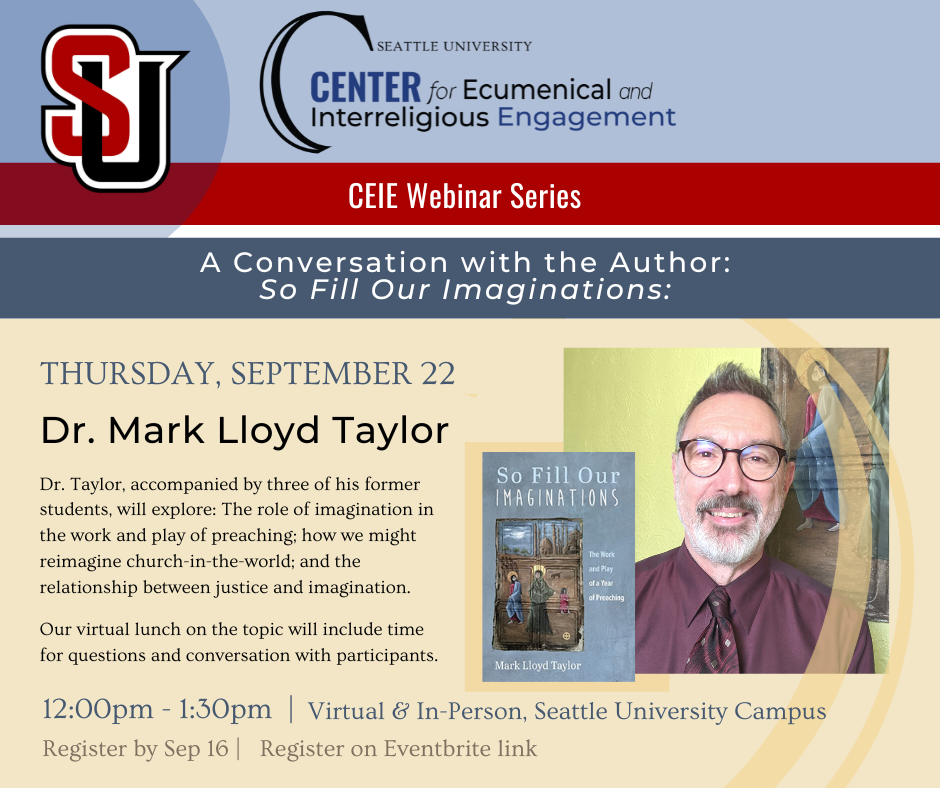

Imagining the World

Imagining the World

.png) Hello SU Campus Community,

Hello SU Campus Community,

Thursday, March 28, 9–10 a.m.

Thursday, March 28, 9–10 a.m. Finding the Sacred in All Women: Celebrating our Connections

Finding the Sacred in All Women: Celebrating our Connections Senator Manka Dhingra

Senator Manka Dhingra

The Faculty and Staff of Color Retreat is sponsored by the Endowed Mission Fund and The MOSAIC Center, and offers 15 SU faculty and staff a dedicated space to focus on connection, identity and wellness.

The Faculty and Staff of Color Retreat is sponsored by the Endowed Mission Fund and The MOSAIC Center, and offers 15 SU faculty and staff a dedicated space to focus on connection, identity and wellness.

.PNG) This year signifies the midpoint in Reigniting Our Strategic Directions for 2022-2027. Throughout Winter Quarter, the Office of Strategic Initiatives is actively engaged in a campus-wide listening tour, inviting input from all our faculty, staff and students. Your feedback will play an important role in shaping the content of the upcoming Midway Report, scheduled to be released in May.

This year signifies the midpoint in Reigniting Our Strategic Directions for 2022-2027. Throughout Winter Quarter, the Office of Strategic Initiatives is actively engaged in a campus-wide listening tour, inviting input from all our faculty, staff and students. Your feedback will play an important role in shaping the content of the upcoming Midway Report, scheduled to be released in May. Thursday, April 4, 5–6:30 p.m.

Thursday, April 4, 5–6:30 p.m. Tuesday, March 12, noon

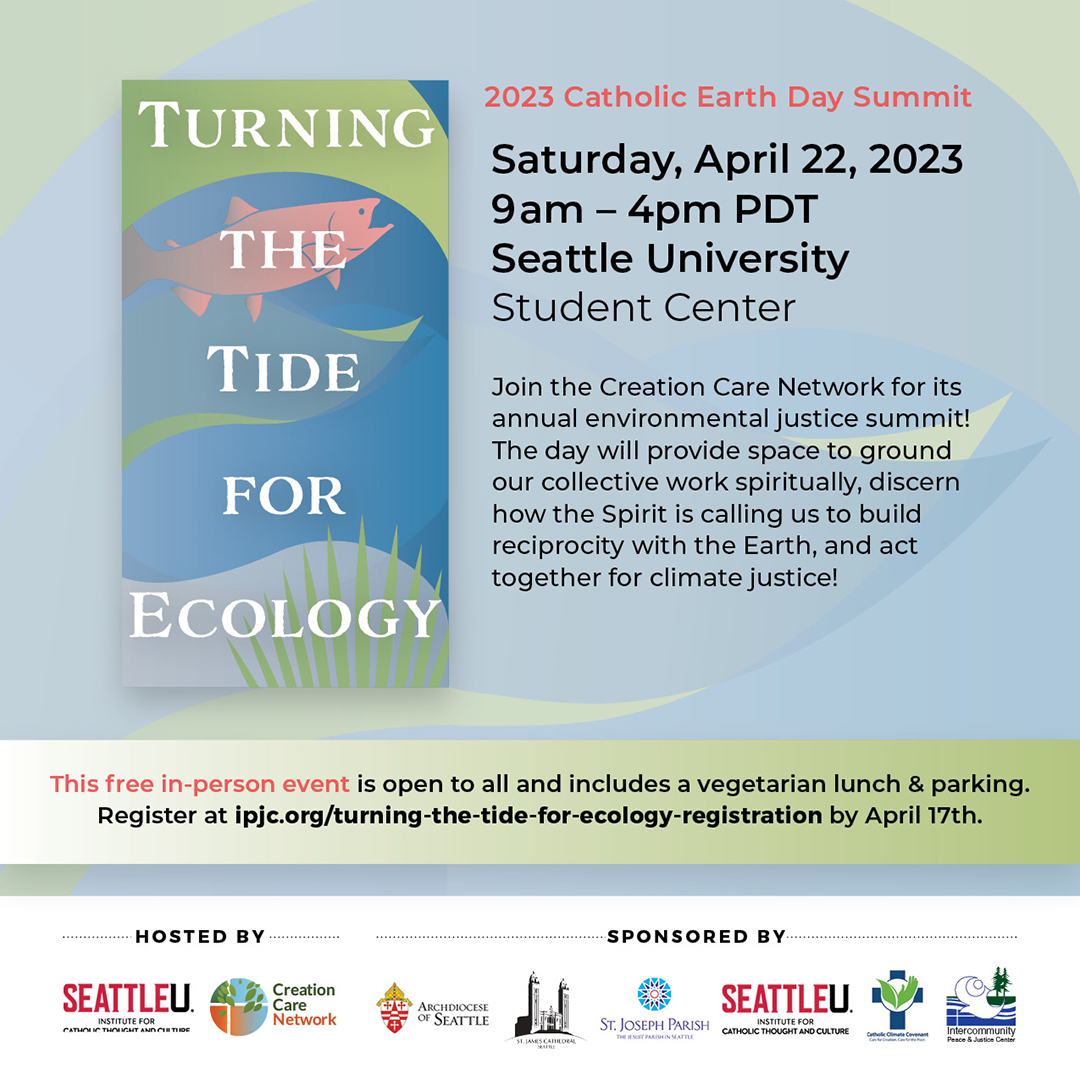

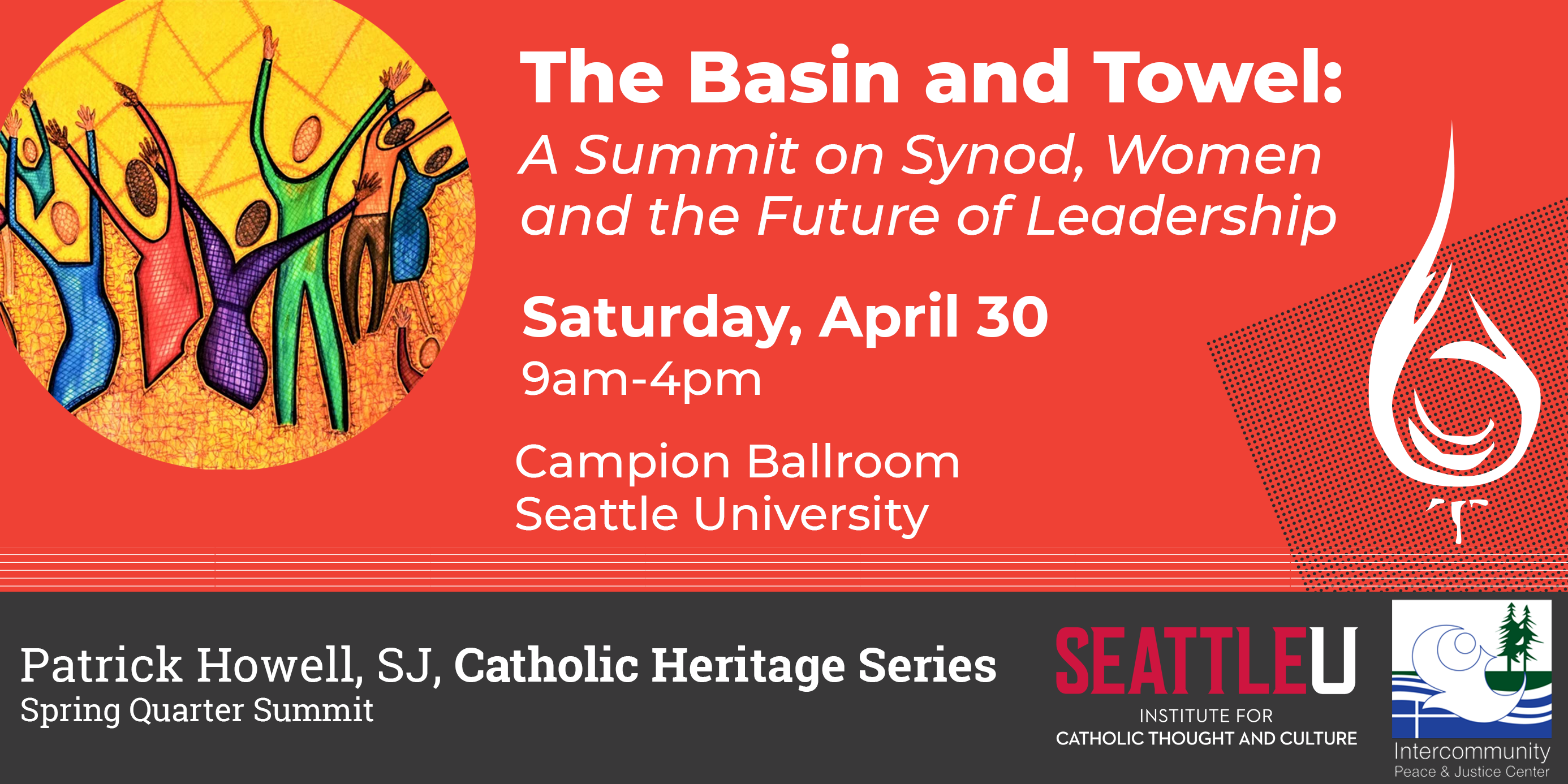

Tuesday, March 12, noon Saturday, March 16, 9 a.m.– 4 p.m.

Saturday, March 16, 9 a.m.– 4 p.m. Thursday, March 7, 4:30-7:30 p.m.

Thursday, March 7, 4:30-7:30 p.m. Wednesday, March 6, 4:30–7:30 p.m.

Wednesday, March 6, 4:30–7:30 p.m. Dr. anton ward-zanotto with Dr. Tess Barker, ASCA executive director, and Christina Parle, ASCA past president. (Photo by Adam Bacher)

Dr. anton ward-zanotto with Dr. Tess Barker, ASCA executive director, and Christina Parle, ASCA past president. (Photo by Adam Bacher)

“Celebrating the Sacred: Making Connections through Creativity”

“Celebrating the Sacred: Making Connections through Creativity”

_Page_1.png)

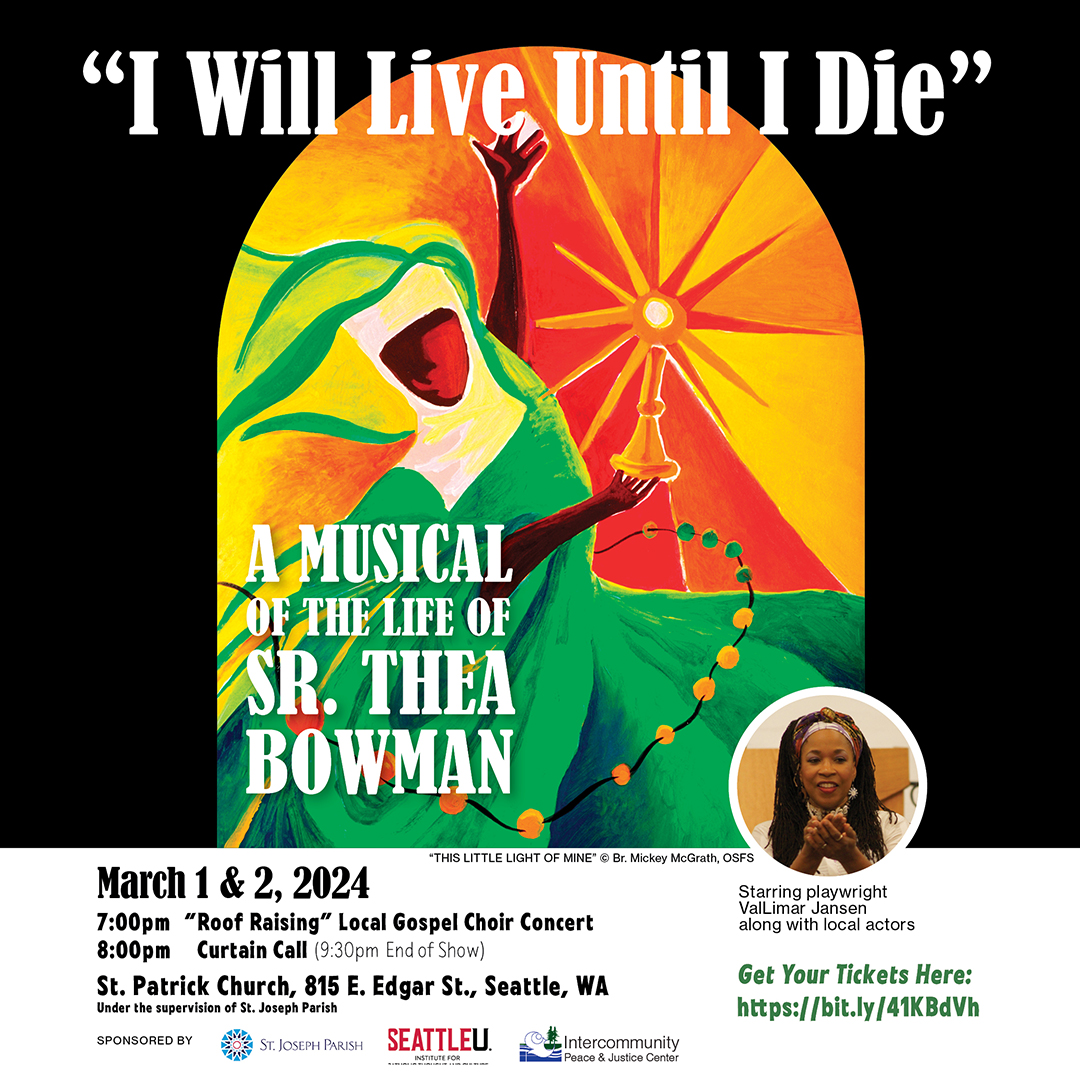

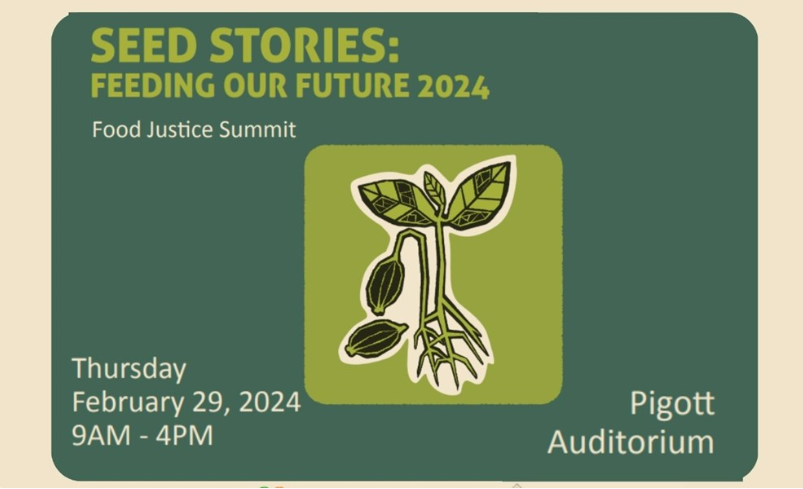

Thursday, Feb. 29, noon to 2 p.m.

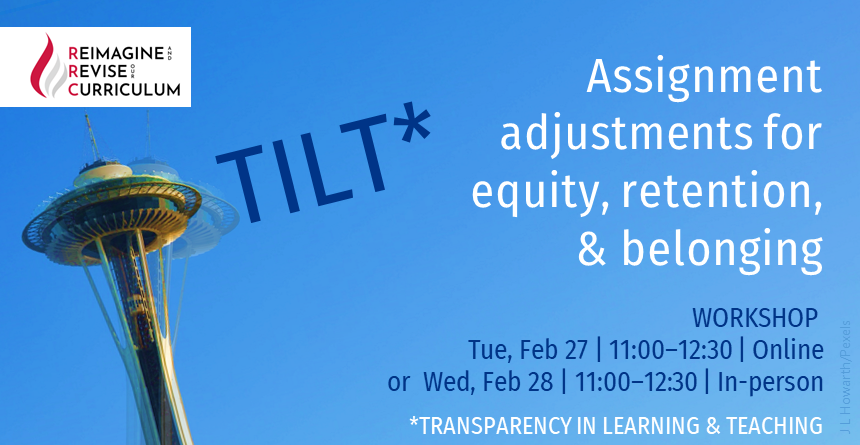

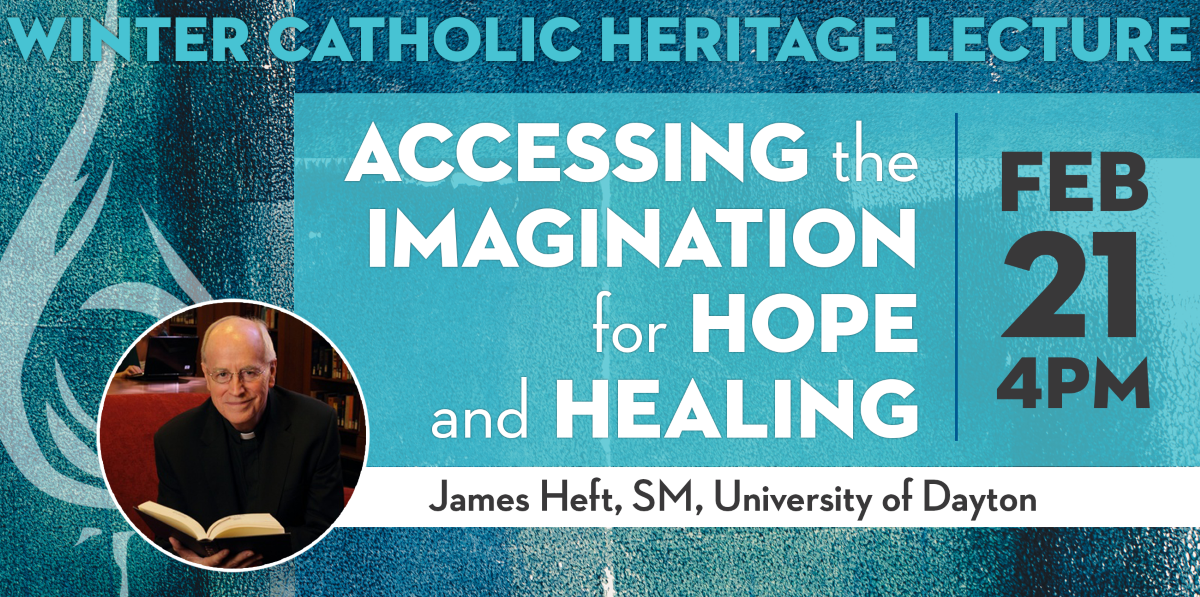

Thursday, Feb. 29, noon to 2 p.m. Winter Catholic Heritage Lecture:

Winter Catholic Heritage Lecture:

.png)

Assistant Director of Graduate International Admissions LesLee Clauson Eicher is being honored with a national award from the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (

Assistant Director of Graduate International Admissions LesLee Clauson Eicher is being honored with a national award from the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (

.png)

Tuesday, Feb. 13, 12:30–1:20 p.m.

Tuesday, Feb. 13, 12:30–1:20 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 15, 6–8 p.m.

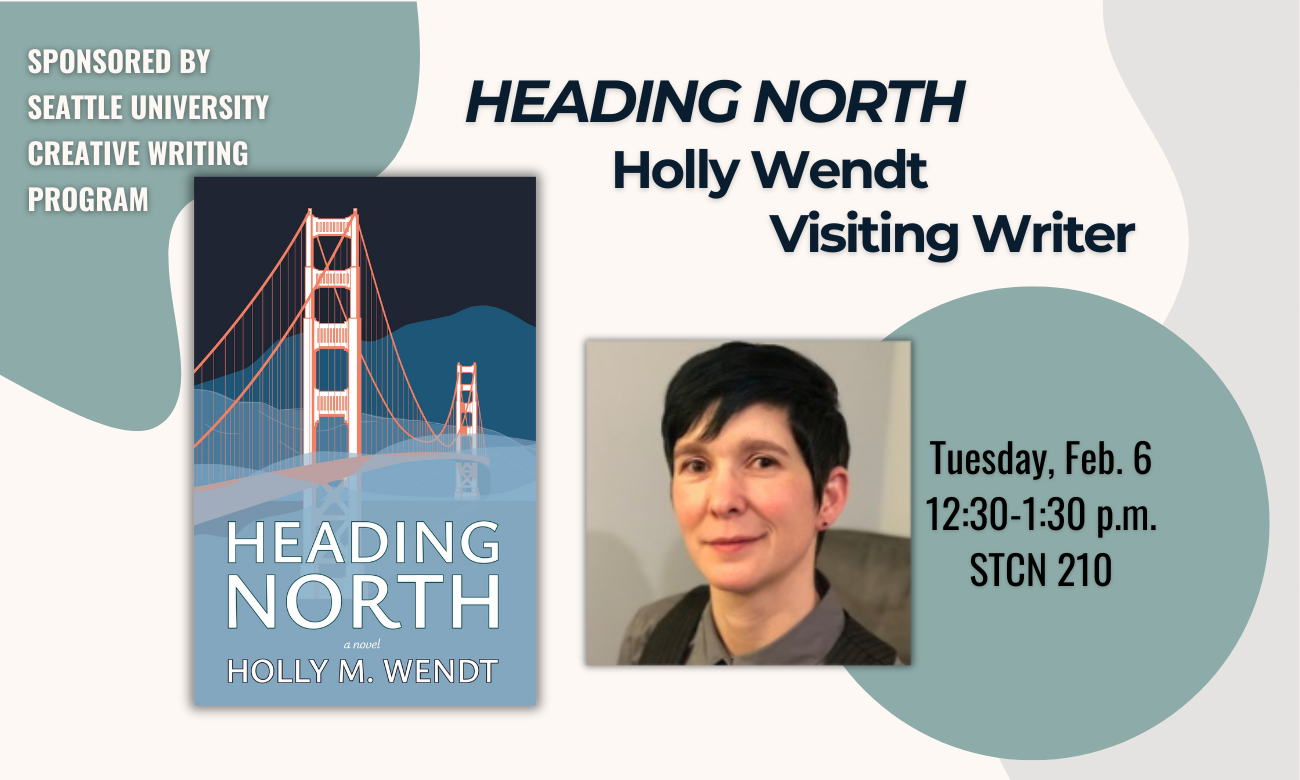

Thursday, Feb. 15, 6–8 p.m. “Heading North” by Holly Wendt, Visiting Writer

“Heading North” by Holly Wendt, Visiting Writer

The Orientation Leader position is an exciting opportunity to build community and belonging at SU while developing transferable skills that will prepare students for future career opportunities.

The Orientation Leader position is an exciting opportunity to build community and belonging at SU while developing transferable skills that will prepare students for future career opportunities.

Photo by Nodoka Kondo

Photo by Nodoka Kondo What is the Campus Race to Zero Waste Competition? It is an eight-week recycling competition from late January through late March between colleges and universities across North America. Participants compete to see how much materials they can divert from the landfill and gauge how they compare against other institutions!

What is the Campus Race to Zero Waste Competition? It is an eight-week recycling competition from late January through late March between colleges and universities across North America. Participants compete to see how much materials they can divert from the landfill and gauge how they compare against other institutions!

Tuesday, Feb. 20

Tuesday, Feb. 20

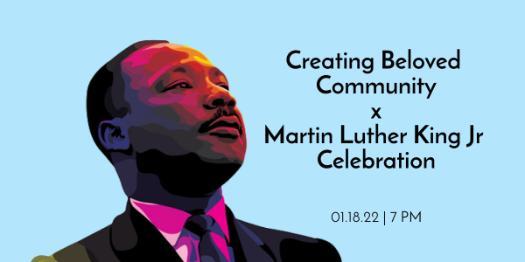

Monday, Jan. 15, 11 a.m.-12:30 p.m.

Monday, Jan. 15, 11 a.m.-12:30 p.m. Did you know that SU has its own coffee brand? MotMot Coffee, led and run by Albers students, is back with new stock, a new team, and new packaging. You can order your bags on

Did you know that SU has its own coffee brand? MotMot Coffee, led and run by Albers students, is back with new stock, a new team, and new packaging. You can order your bags on

The Undergraduate Admissions Office is proud to introduce a brand-new virtual tour! Future Redhawks can explore the campus from the comfort of anywhere on

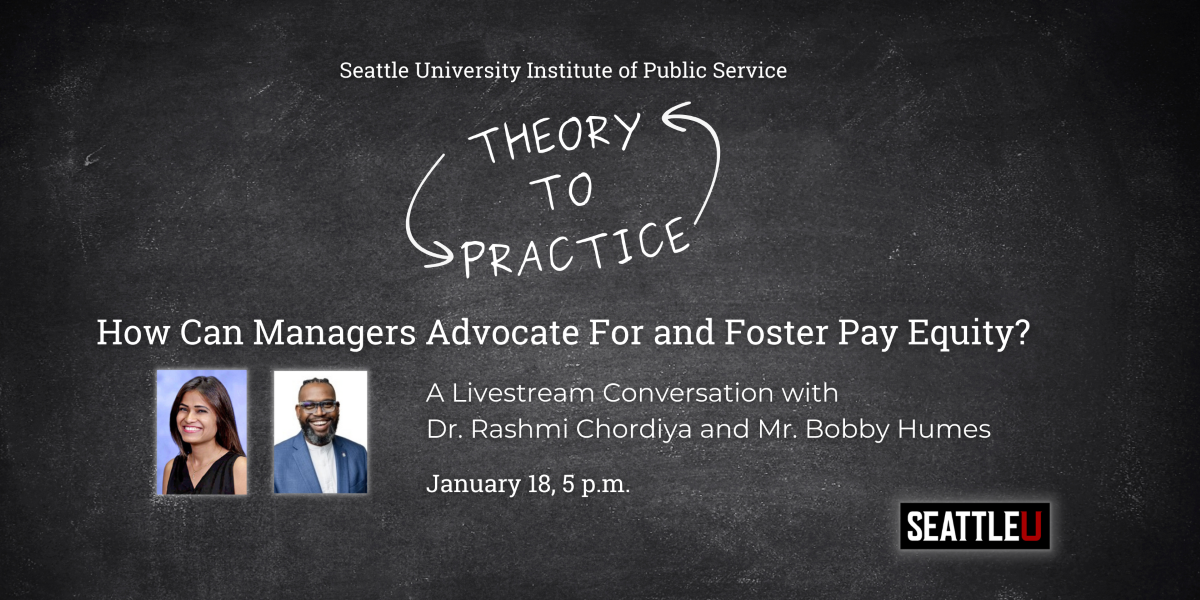

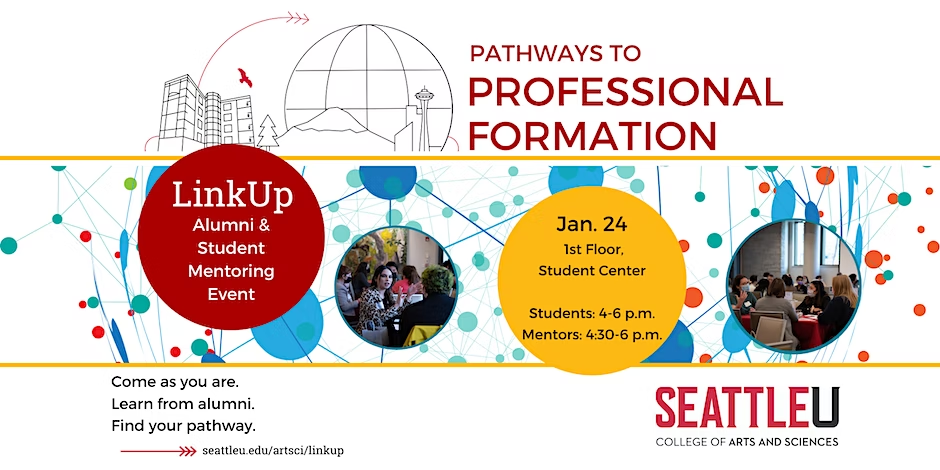

The Undergraduate Admissions Office is proud to introduce a brand-new virtual tour! Future Redhawks can explore the campus from the comfort of anywhere on  Thursdays, Jan. 11, 18, 25, and Feb. 1

Thursdays, Jan. 11, 18, 25, and Feb. 1

Monday, Nov. 27, noon

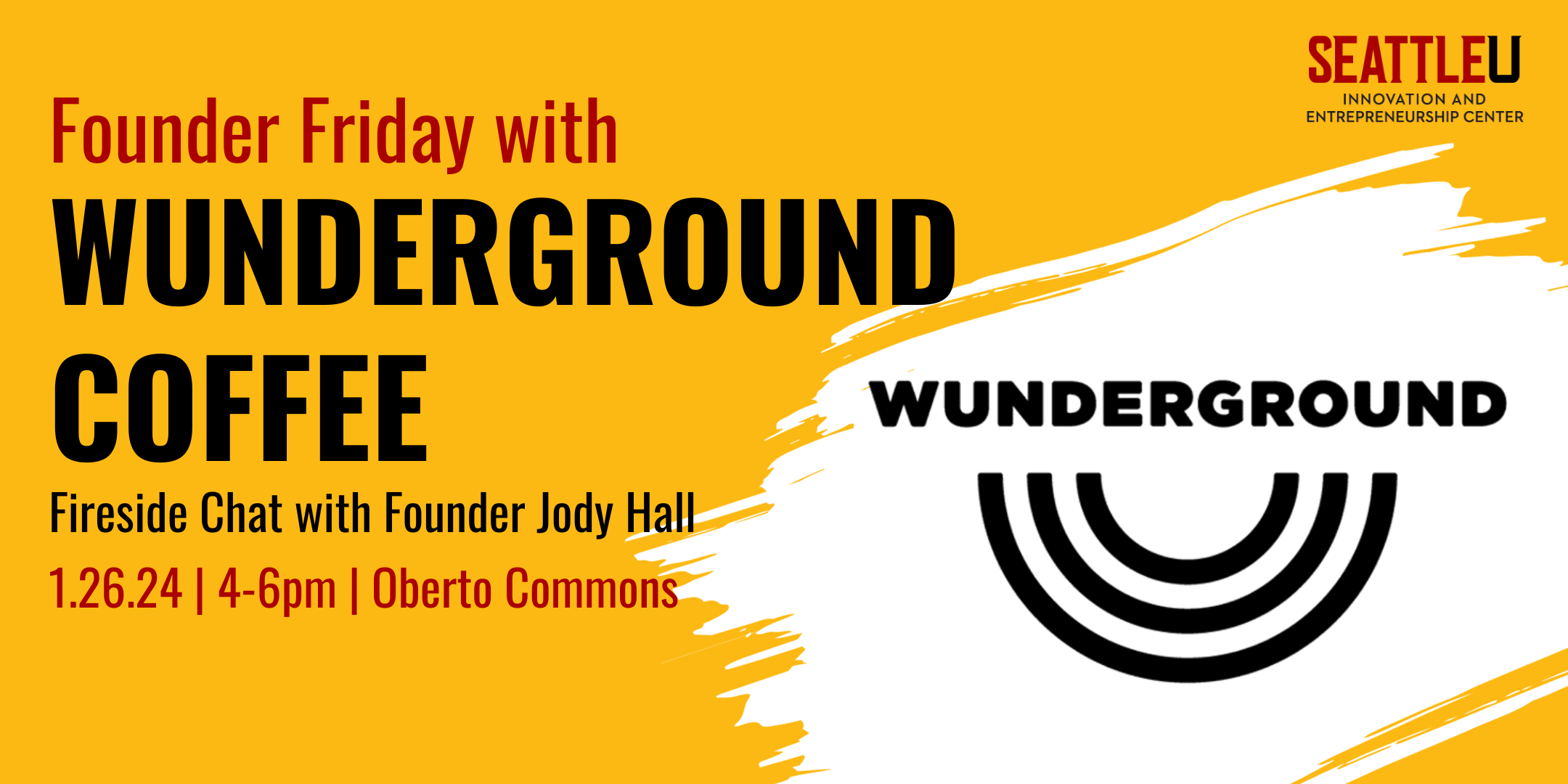

Monday, Nov. 27, noon Erika Cheung, a key whistleblower in the Theranos case that gripped the world, will be speaking at the Albers School of Business and Economics on April 4, 2024. Her visit is being organized by the

Erika Cheung, a key whistleblower in the Theranos case that gripped the world, will be speaking at the Albers School of Business and Economics on April 4, 2024. Her visit is being organized by the

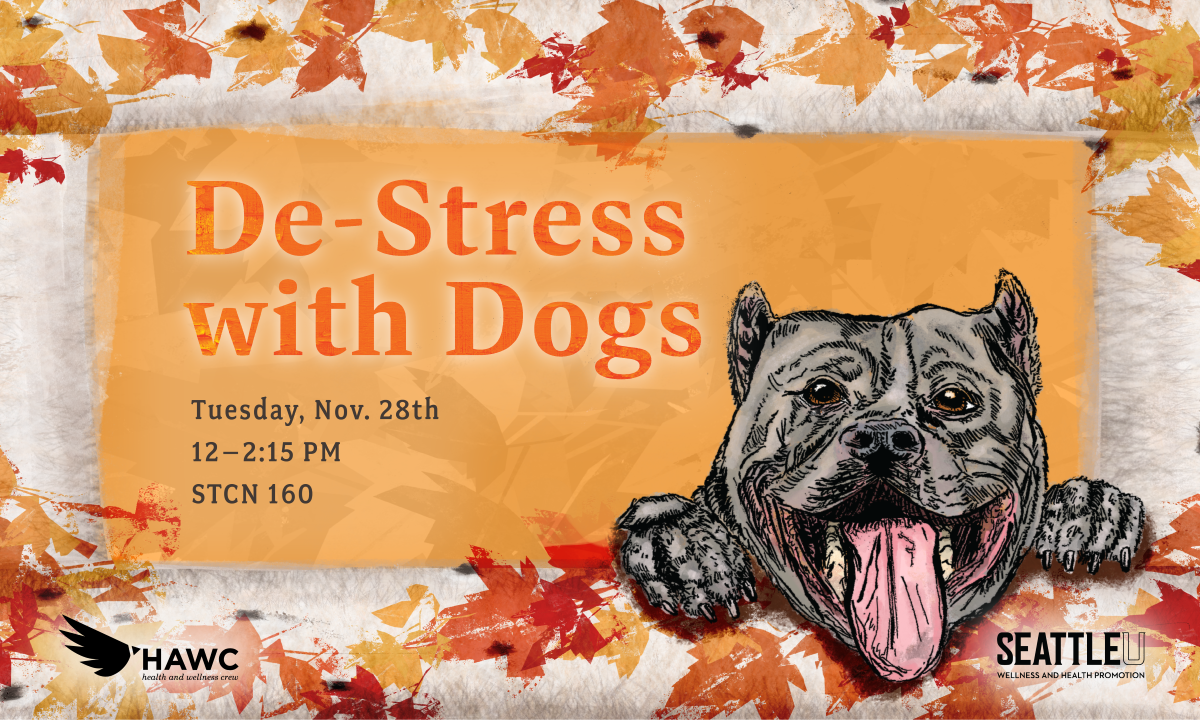

De-Stress with Dogs, the Health and Wellness Crew’s signature and most popular event, will be held on Tuesday, Nov. 28 from 1 to 2:15 p.m. in the LeRoux Conference Room (STCN 160).

De-Stress with Dogs, the Health and Wellness Crew’s signature and most popular event, will be held on Tuesday, Nov. 28 from 1 to 2:15 p.m. in the LeRoux Conference Room (STCN 160).

Tuesday, Nov. 21, between 11:30 a.m. and 1 p.m.

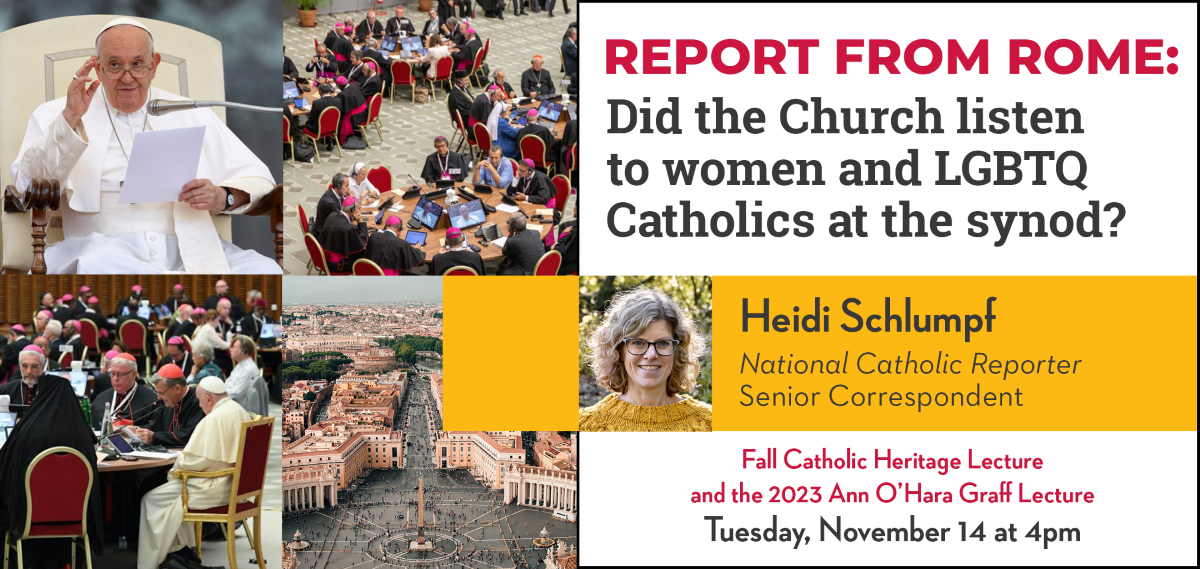

Tuesday, Nov. 21, between 11:30 a.m. and 1 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 14, 4 p.m.

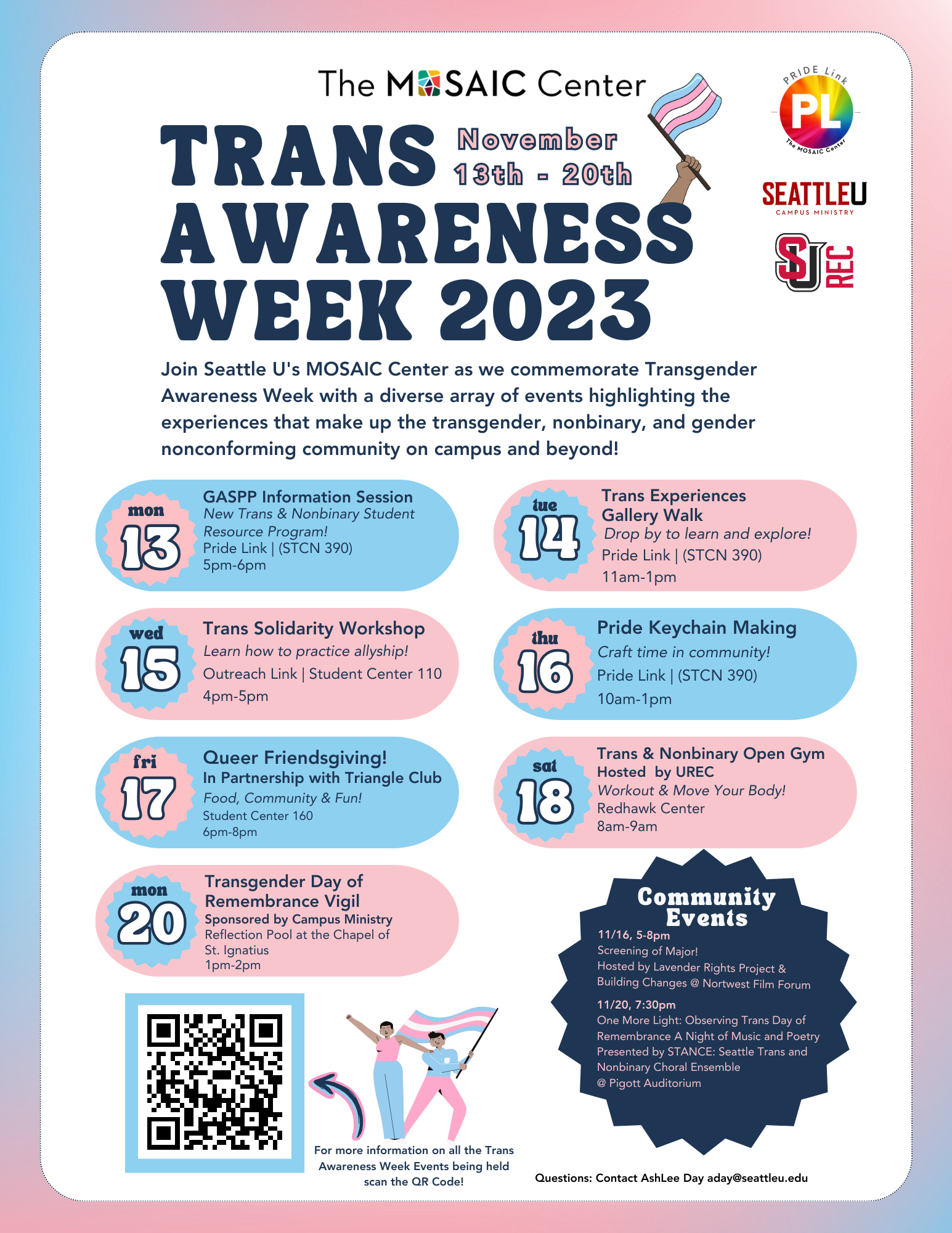

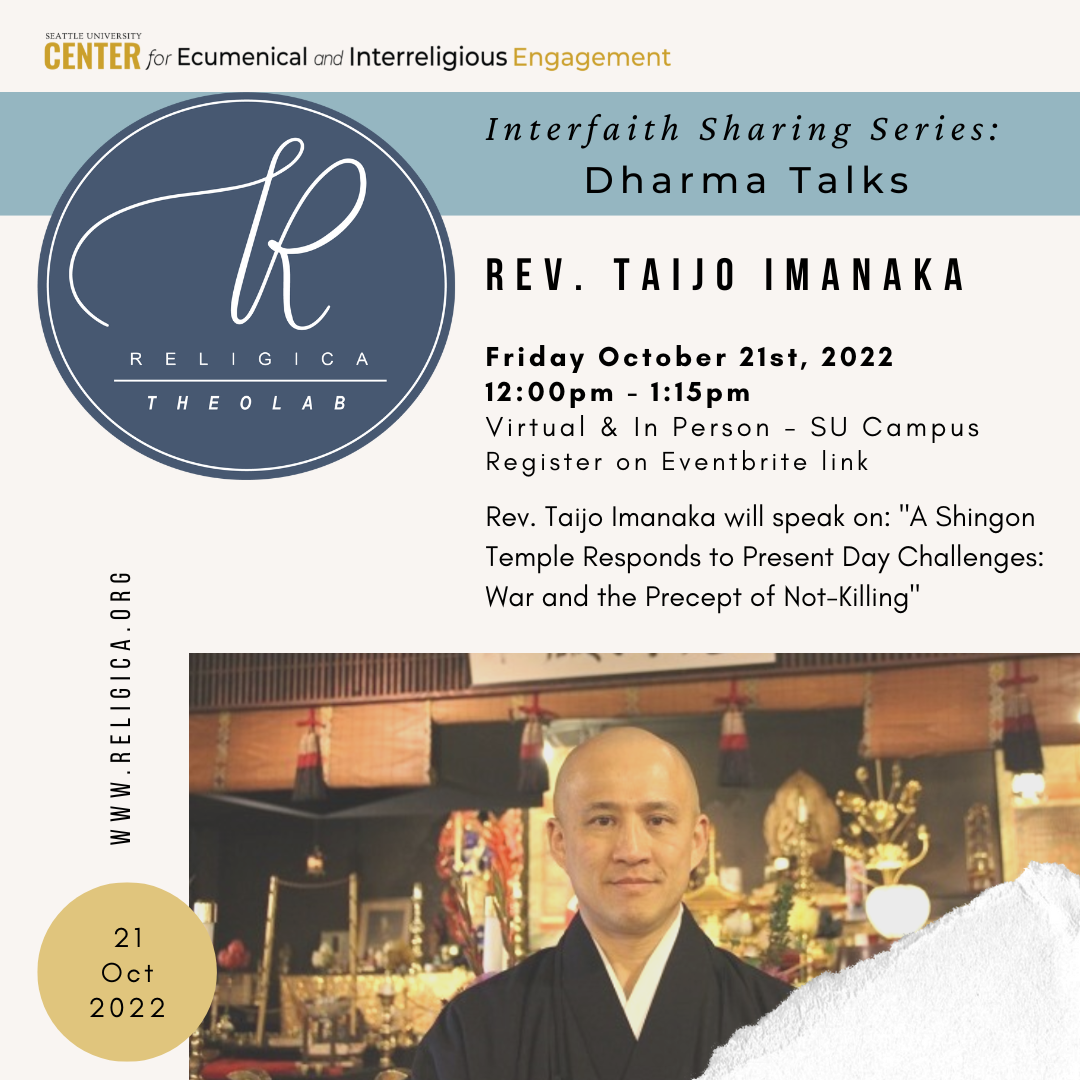

Tuesday, Nov. 14, 4 p.m. View the Interfaith Roundup here

View the Interfaith Roundup here

Dear Campus Partners,

Dear Campus Partners, All are invited to celebrate Halloween with these fun activities on campus Tuesday, Oct. 31.

All are invited to celebrate Halloween with these fun activities on campus Tuesday, Oct. 31.

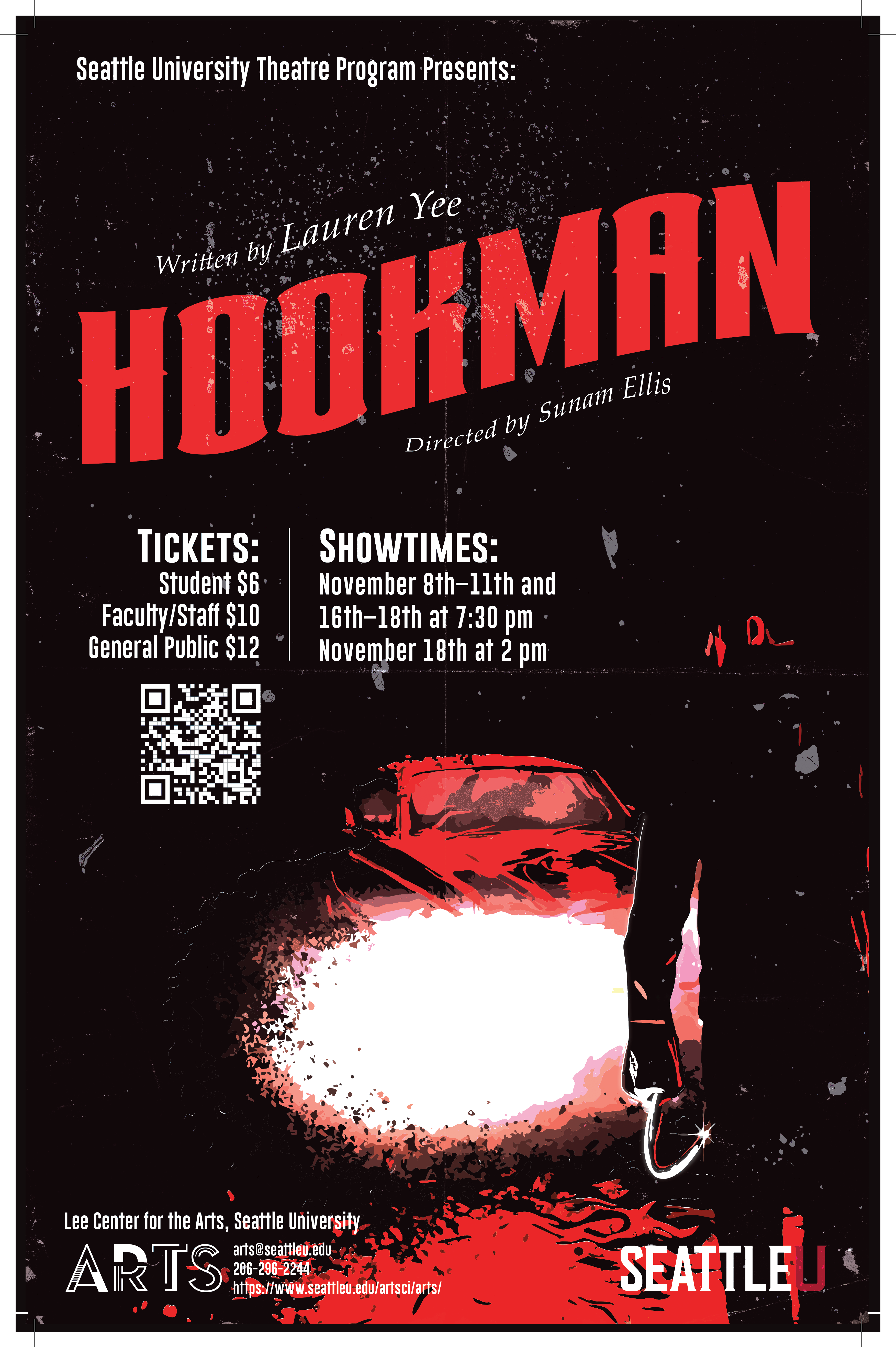

Homecoming is returning to Seattle University Nov. 6–12! Join students, alumni, faculty, staff, friends and family for a week-long campus celebration packed with a series of events, programs and gameday traditions for the Redhawk community to enjoy, including:

Homecoming is returning to Seattle University Nov. 6–12! Join students, alumni, faculty, staff, friends and family for a week-long campus celebration packed with a series of events, programs and gameday traditions for the Redhawk community to enjoy, including:

Laudate Deum: A discussion on Pope Francis' new Apostolic Exhortation

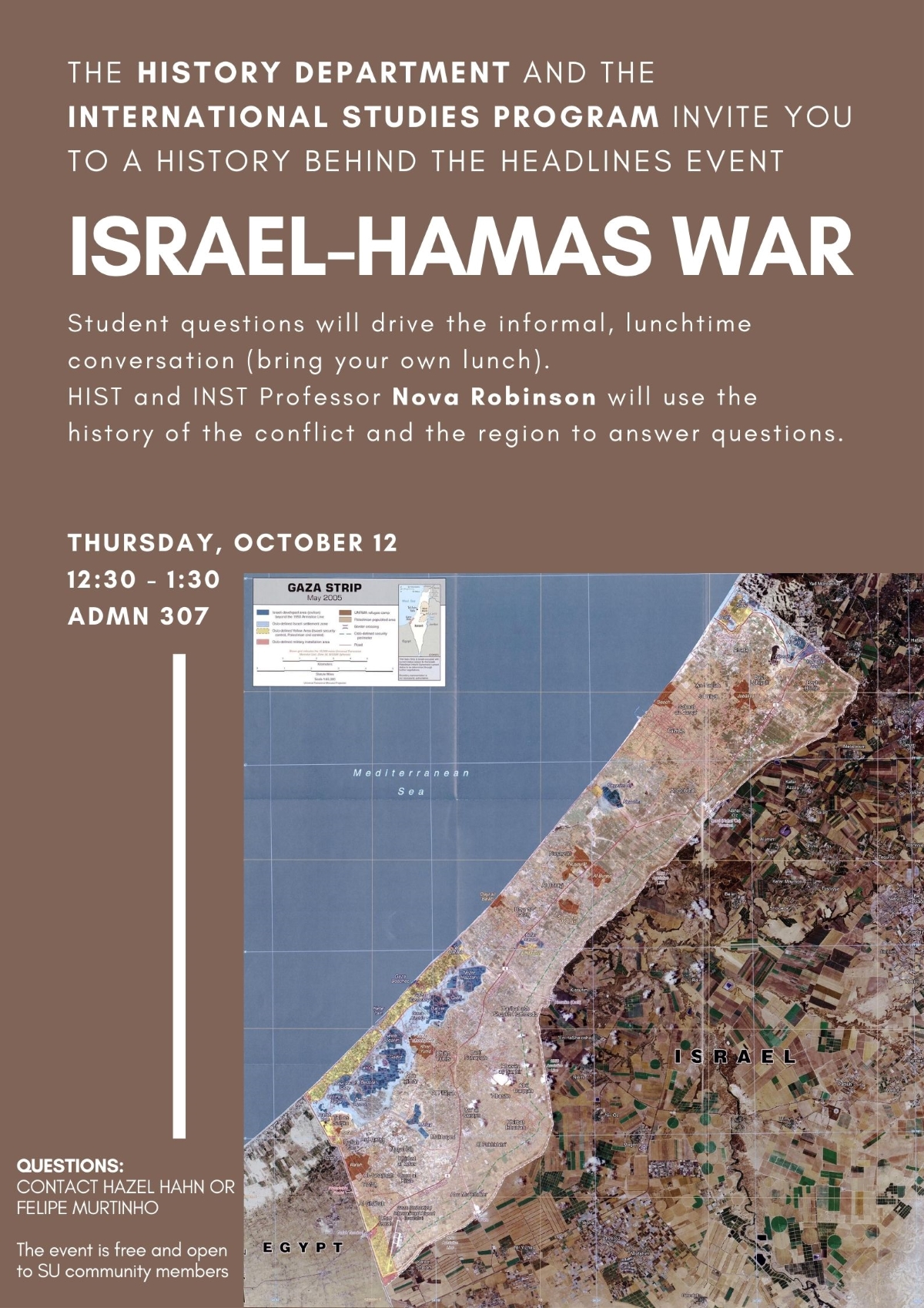

Laudate Deum: A discussion on Pope Francis' new Apostolic Exhortation We join Pope Francis in expressing solidarity with the victims of the attacks in Israel over the weekend, and in his prayers for their families, all those living in “terror and anguish” and for peace and healing.

We join Pope Francis in expressing solidarity with the victims of the attacks in Israel over the weekend, and in his prayers for their families, all those living in “terror and anguish” and for peace and healing.

Saturday, Oct. 21, 10 a.m.–3:30 p.m., lunch included

Saturday, Oct. 21, 10 a.m.–3:30 p.m., lunch included

Friday, Sept. 29, 3-5 p.m.

Friday, Sept. 29, 3-5 p.m. Friday, Nov. 3, noon–2 p.m.

Friday, Nov. 3, noon–2 p.m.

Student & Campus Life is excited to announce a new program aimed at addressing the increasing use of

Student & Campus Life is excited to announce a new program aimed at addressing the increasing use of

.png)

Read the

Read the

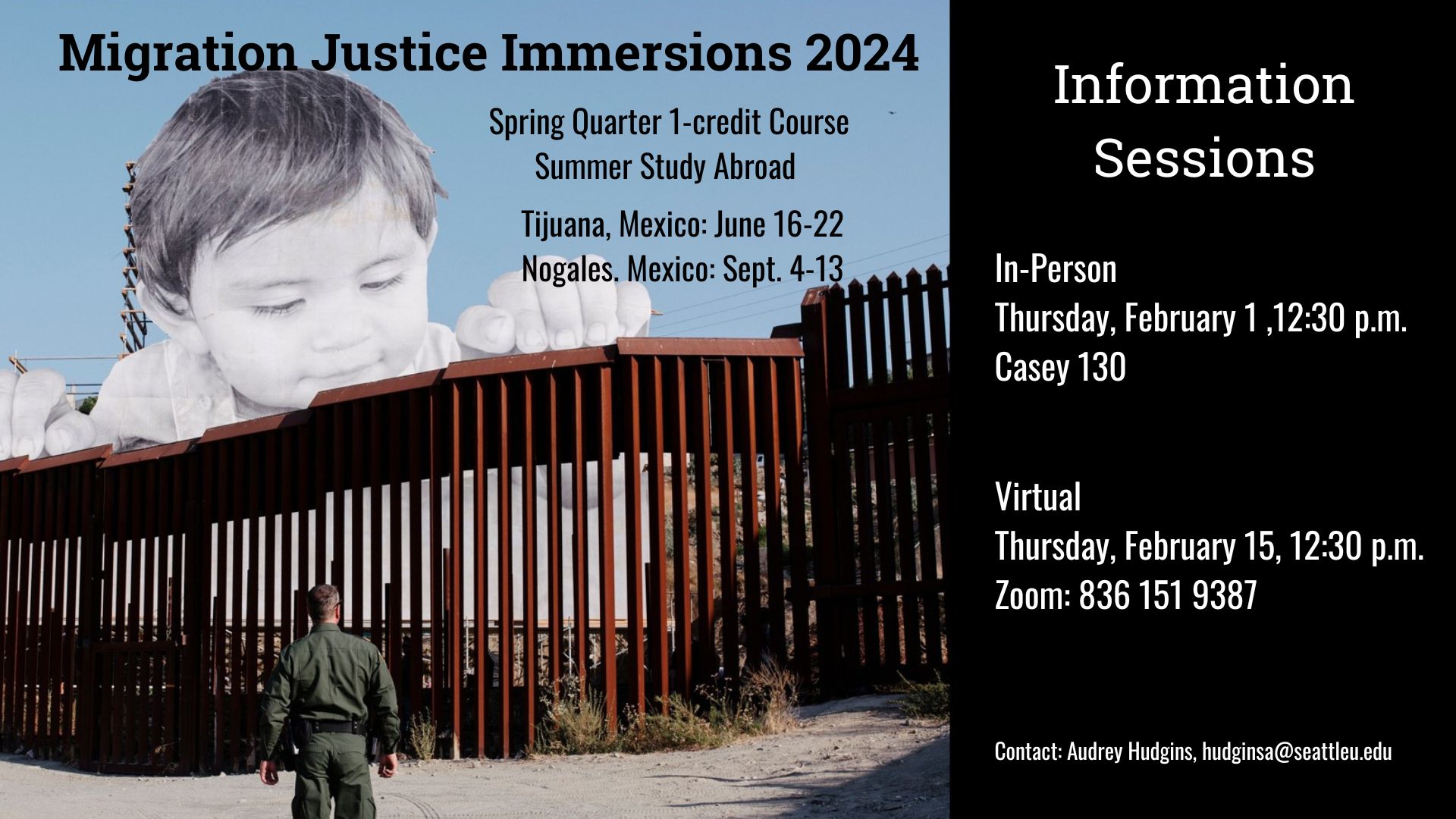

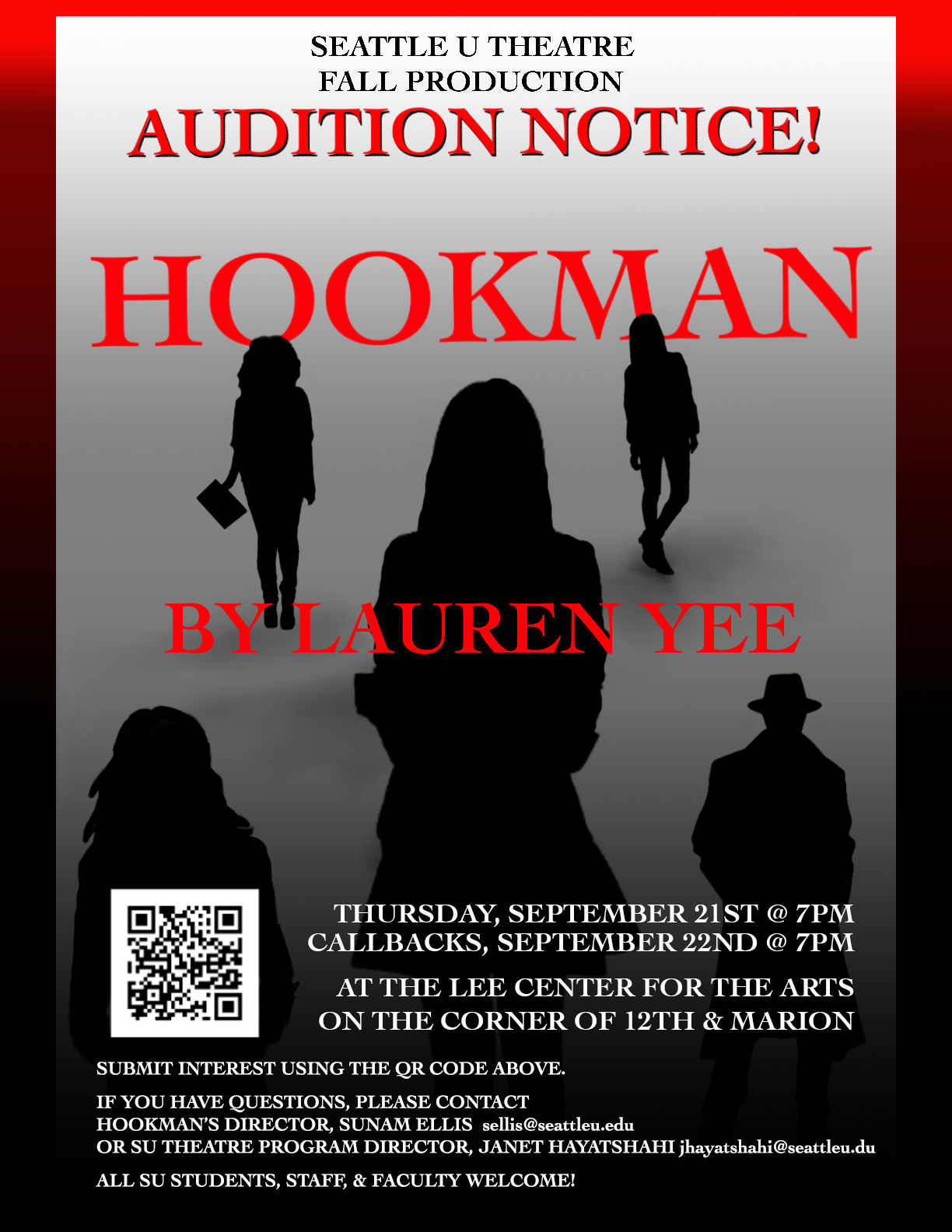

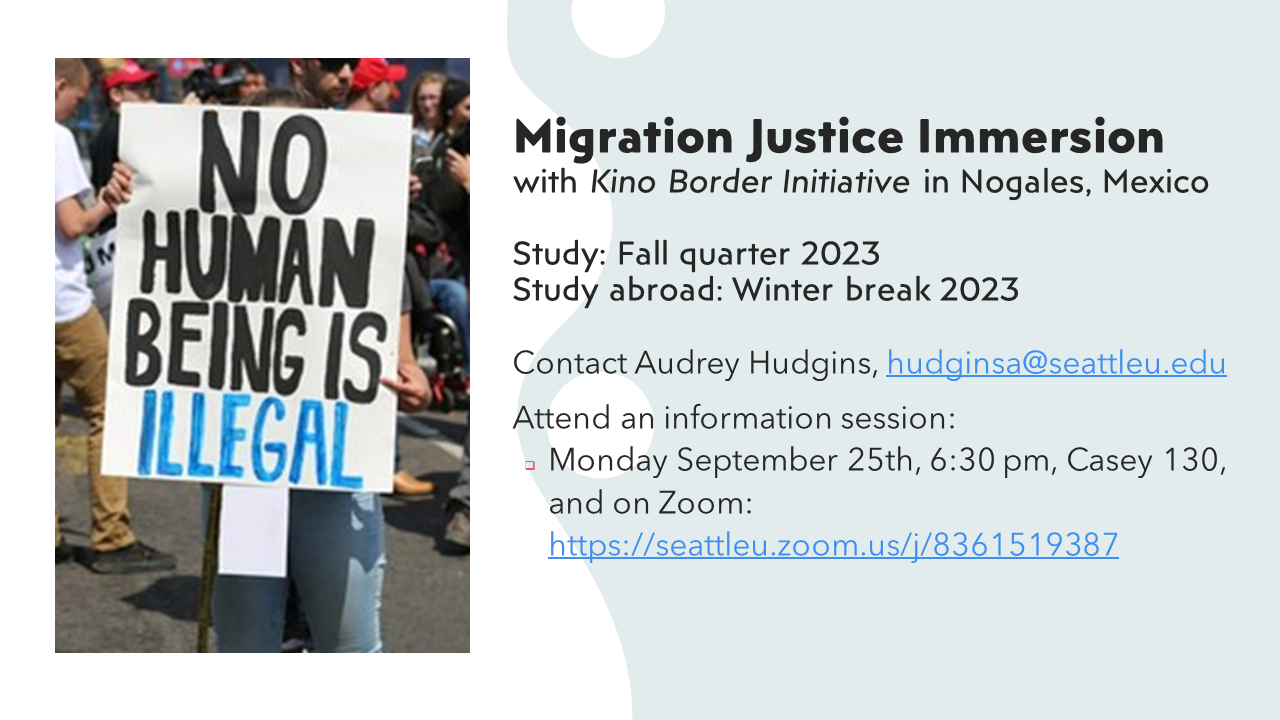

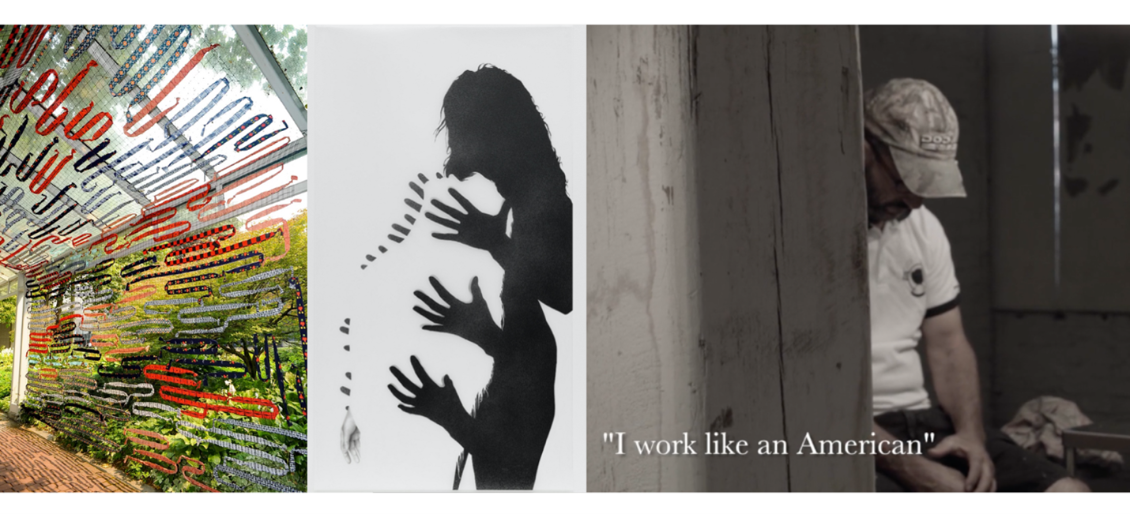

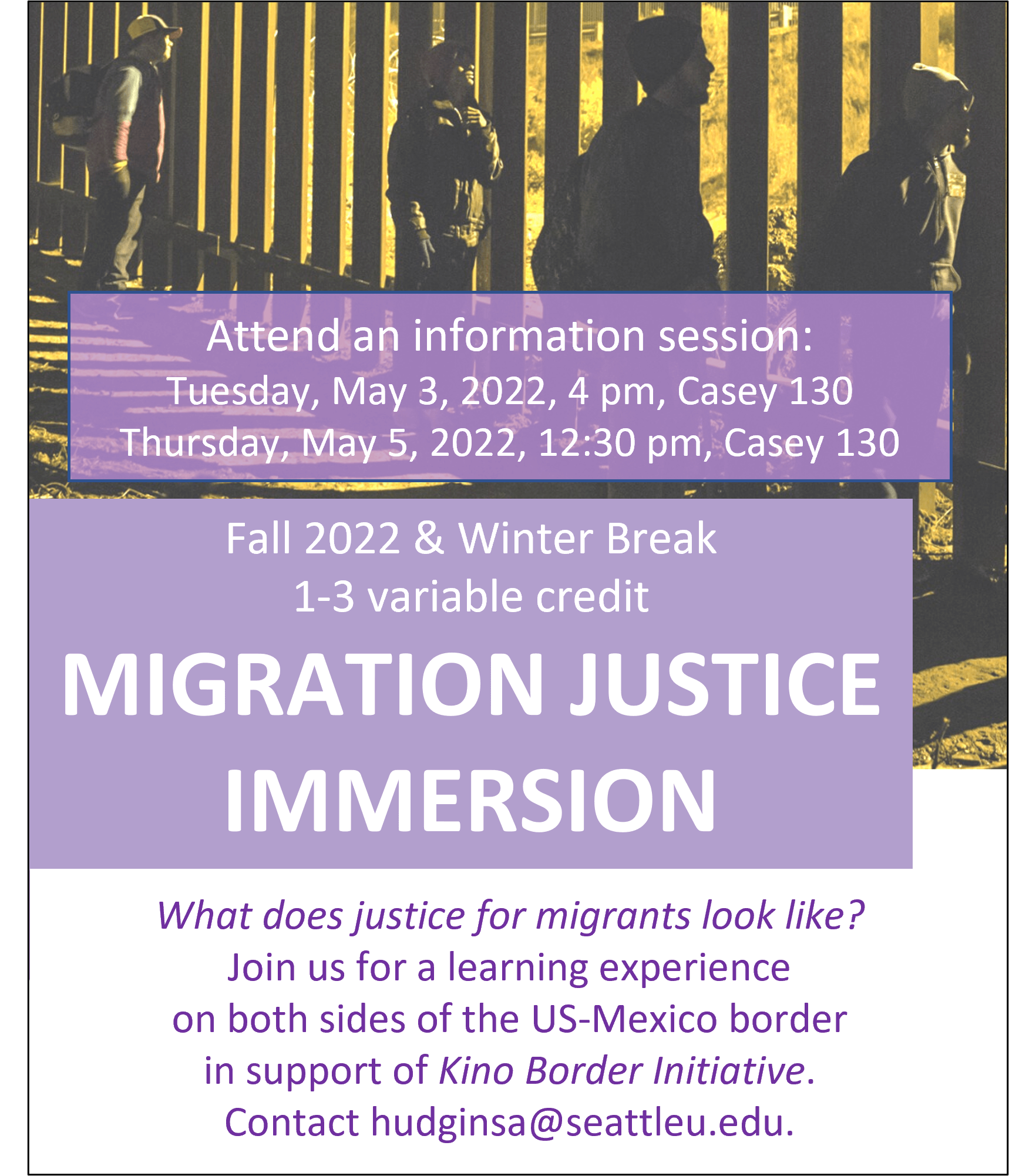

Migration Justice Immersion in Mexico (23FQ course, Winter break 2023 travel)

Migration Justice Immersion in Mexico (23FQ course, Winter break 2023 travel)

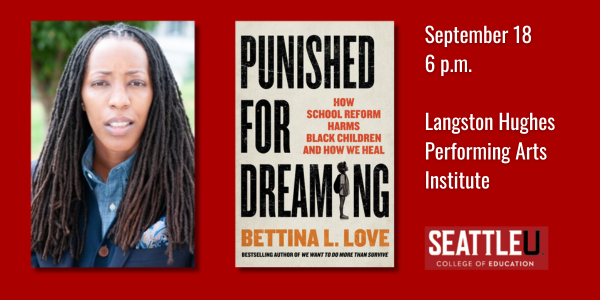

Monday, Sept. 18, 6 p.m.

Monday, Sept. 18, 6 p.m.

-(1).jpg)

The strategic partnership between India and the United States to promote global security, trade and investment has never been stronger. Seattle-Setu showcases Seattle’s pivotal role in building economic and political bridges with India.

The strategic partnership between India and the United States to promote global security, trade and investment has never been stronger. Seattle-Setu showcases Seattle’s pivotal role in building economic and political bridges with India.

We are excited to introduce you to The MOSAIC Center (formerly the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Student Success & Outreach). The center’s purpose and function is to create Meaningful Opportunities for Student Access, Inclusion and Community.

We are excited to introduce you to The MOSAIC Center (formerly the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Student Success & Outreach). The center’s purpose and function is to create Meaningful Opportunities for Student Access, Inclusion and Community. Earlier this year President Peñalver shared an update regarding the APSR focused on Event Planning & Coordination, which outlined the reorganization of the university’s event planning functions. To get a full picture of all the events hosted by Seattle University, the University Events team is conducting a comprehensive event audit. Through this audit the team will compile a report that will be shared with Senior Leadership in late summer. The report will include an initial assessment of the comprehensive event landscape, recommendations for categorizing events into the above-mentioned segments and further recommendations for reimagining, sunsetting or amplifying engagements.

Earlier this year President Peñalver shared an update regarding the APSR focused on Event Planning & Coordination, which outlined the reorganization of the university’s event planning functions. To get a full picture of all the events hosted by Seattle University, the University Events team is conducting a comprehensive event audit. Through this audit the team will compile a report that will be shared with Senior Leadership in late summer. The report will include an initial assessment of the comprehensive event landscape, recommendations for categorizing events into the above-mentioned segments and further recommendations for reimagining, sunsetting or amplifying engagements. New Student Move-in Day is Saturday, Sept. 16. Be the first to welcome our new students to campus!

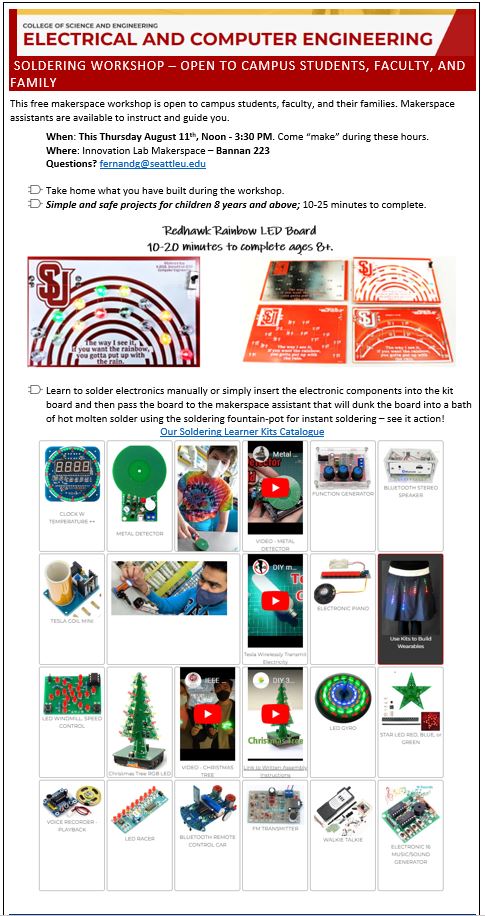

New Student Move-in Day is Saturday, Sept. 16. Be the first to welcome our new students to campus!  From the College of Science and Engineering:

From the College of Science and Engineering:

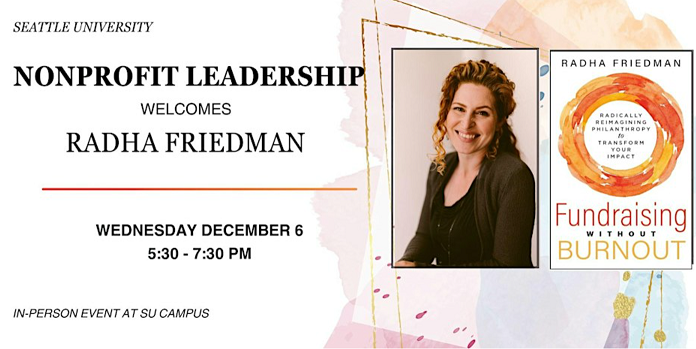

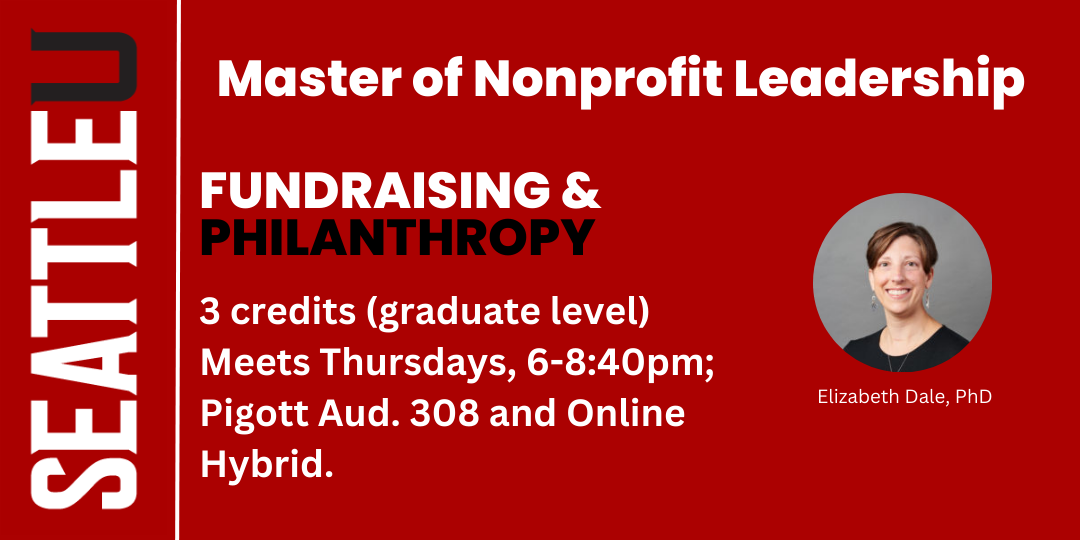

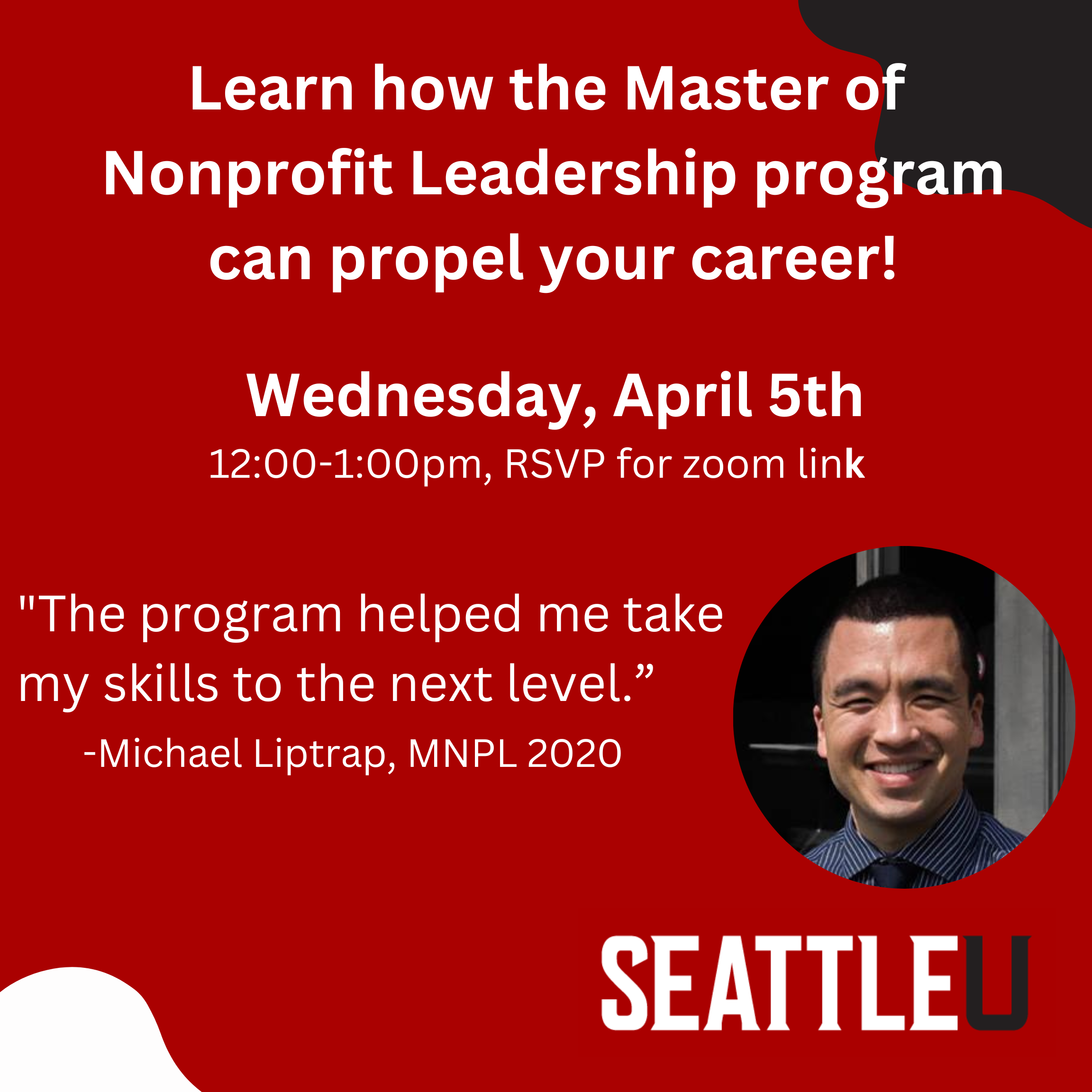

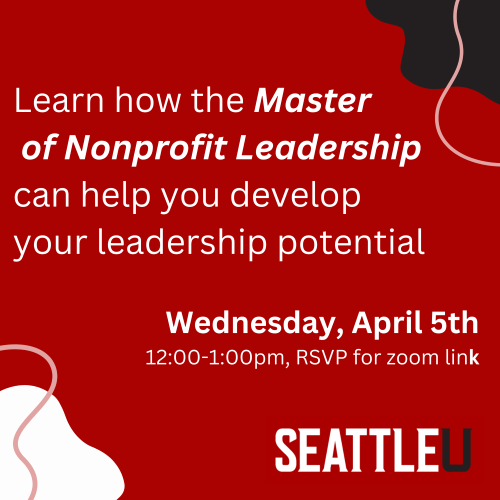

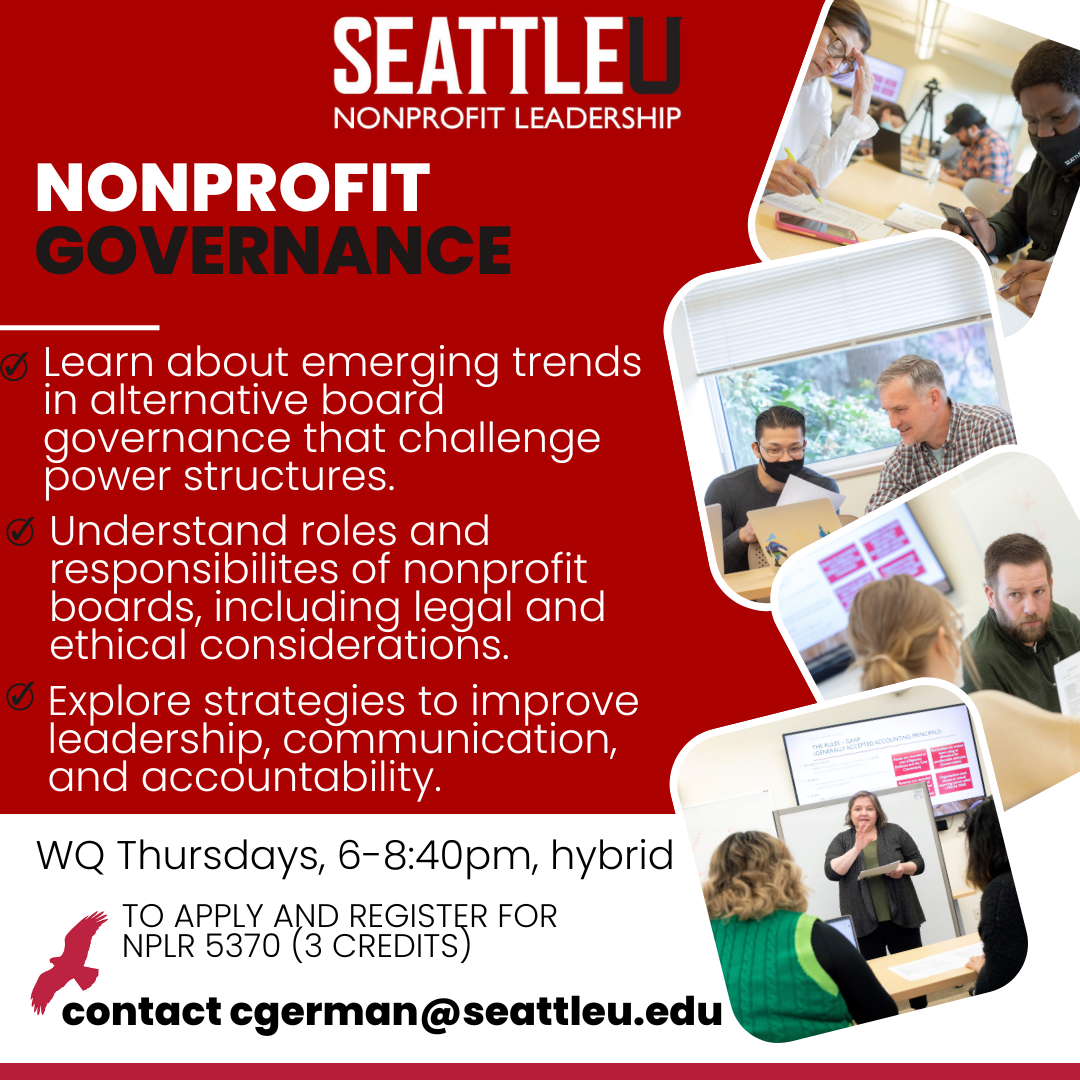

NPLR 5430: Fundraising and Philanthropy

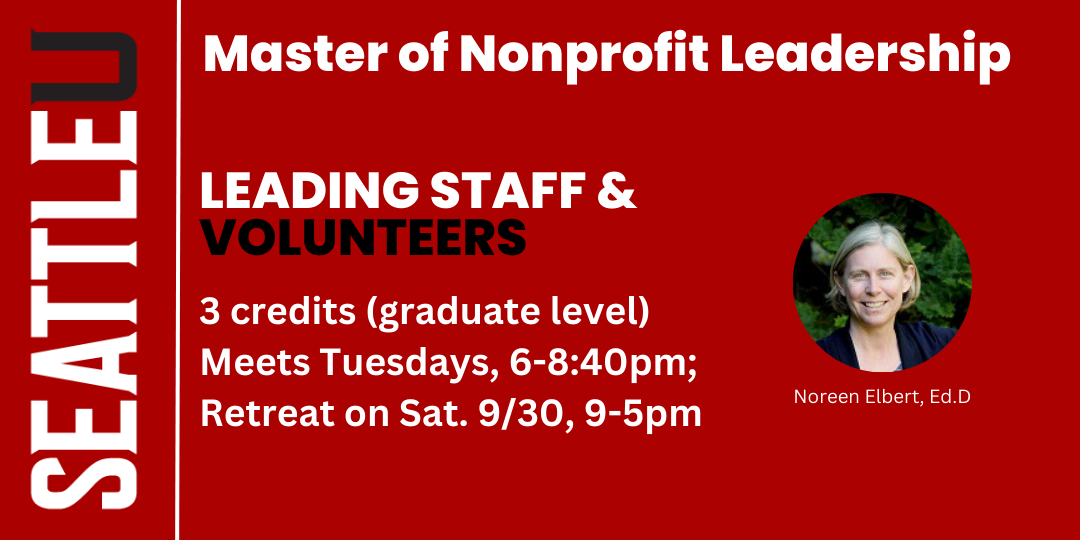

NPLR 5430: Fundraising and Philanthropy  NPLR 5830: Leading Staff & Volunteers

NPLR 5830: Leading Staff & Volunteers

SMER is developing a new technology to extend organ transplant viability and biological functions from 24 hours to months. The startup has established a fully functioning prototype with proof-of-concept results of human cell suspension and animal tissue. SMER is the brainchild of Shen Ren, PhD, assistant teaching professor at Seattle University's College of Engineering, and Vincent Reitinger, BSME '25 (pictured l, r above).

SMER is developing a new technology to extend organ transplant viability and biological functions from 24 hours to months. The startup has established a fully functioning prototype with proof-of-concept results of human cell suspension and animal tissue. SMER is the brainchild of Shen Ren, PhD, assistant teaching professor at Seattle University's College of Engineering, and Vincent Reitinger, BSME '25 (pictured l, r above).

.gif)

Wednesday, June 7, 3:30-5 p.m.

Wednesday, June 7, 3:30-5 p.m.

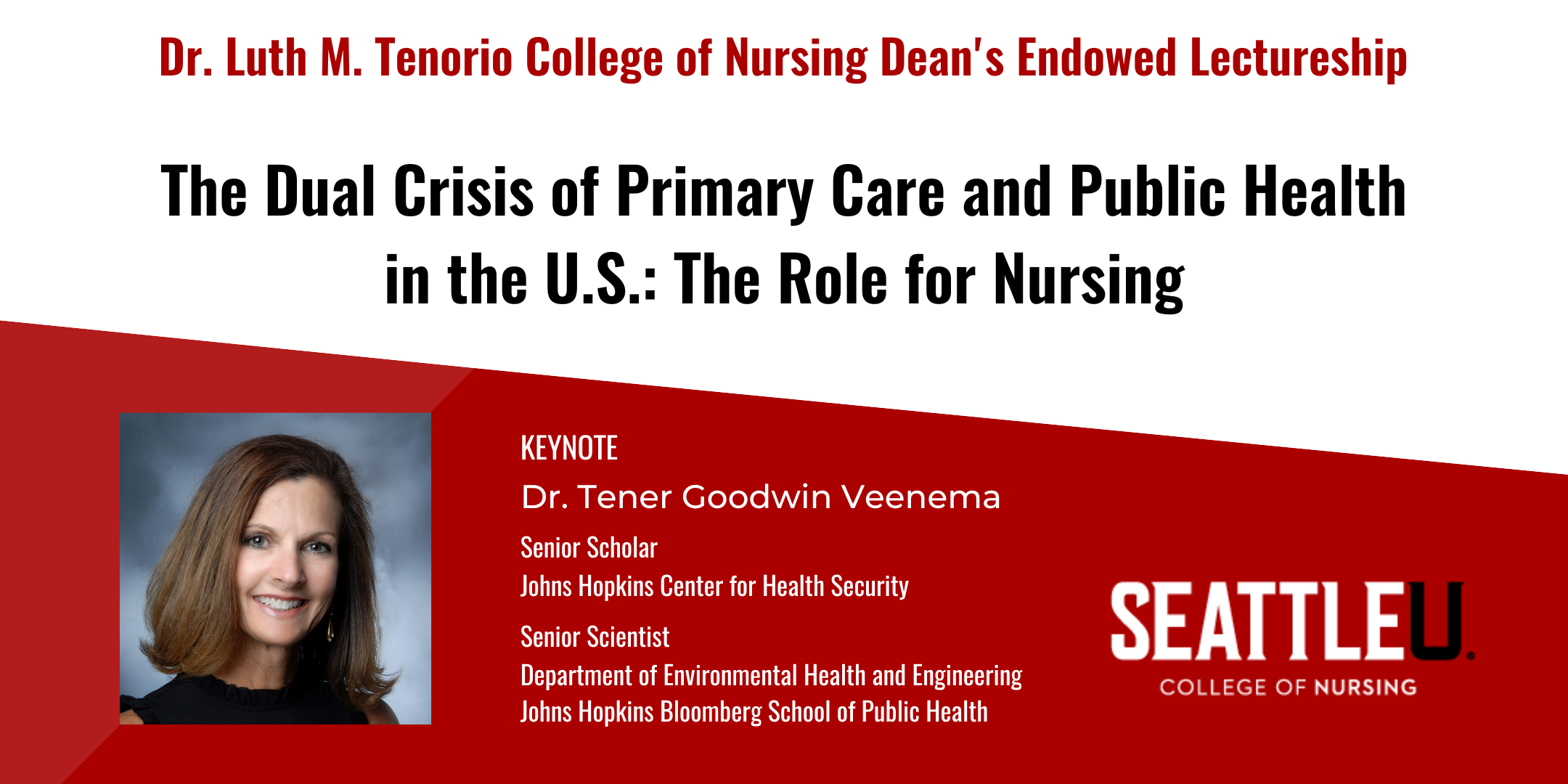

Danuta Wojnar, PhD, RN, MN, MED, IBCLC, FAAN, Professor and N. Jean Bushman Endowed Chair, Associate Dean for Undergraduate Programs in the College of Nursing has been appointed as Dean of the Ila Faye Miller School of Nursing and Health Professions at the University of Incarnate Word in San Antonio Texas. She will begin her new role Aug. 1.

Danuta Wojnar, PhD, RN, MN, MED, IBCLC, FAAN, Professor and N. Jean Bushman Endowed Chair, Associate Dean for Undergraduate Programs in the College of Nursing has been appointed as Dean of the Ila Faye Miller School of Nursing and Health Professions at the University of Incarnate Word in San Antonio Texas. She will begin her new role Aug. 1.

Joining Gonzaga’s Office of Mission and Ministry in 2015, Luke was named Director of Campus Ministry in 2018 and, among other contributions, creatively led the team and ministered to the university community through the challenges of the COVID pandemic.

Joining Gonzaga’s Office of Mission and Ministry in 2015, Luke was named Director of Campus Ministry in 2018 and, among other contributions, creatively led the team and ministered to the university community through the challenges of the COVID pandemic.

Tuesday, May 9, 11:45 a.m.–2 p.m.

Tuesday, May 9, 11:45 a.m.–2 p.m.

Monday, May 8, 4–6 p.m.

Monday, May 8, 4–6 p.m.  Monday, June 5, 4–6:30 p.m.

Monday, June 5, 4–6:30 p.m.

Friday, May 5, 3:30–5:15 p.m.

Friday, May 5, 3:30–5:15 p.m.

Wednesday, April 26, 8 p.m.

Wednesday, April 26, 8 p.m.

Ceremony focuses attention so that attention becomes intention. If you stand together and profess a thing before your community, it holds you accountable.

Ceremony focuses attention so that attention becomes intention. If you stand together and profess a thing before your community, it holds you accountable.

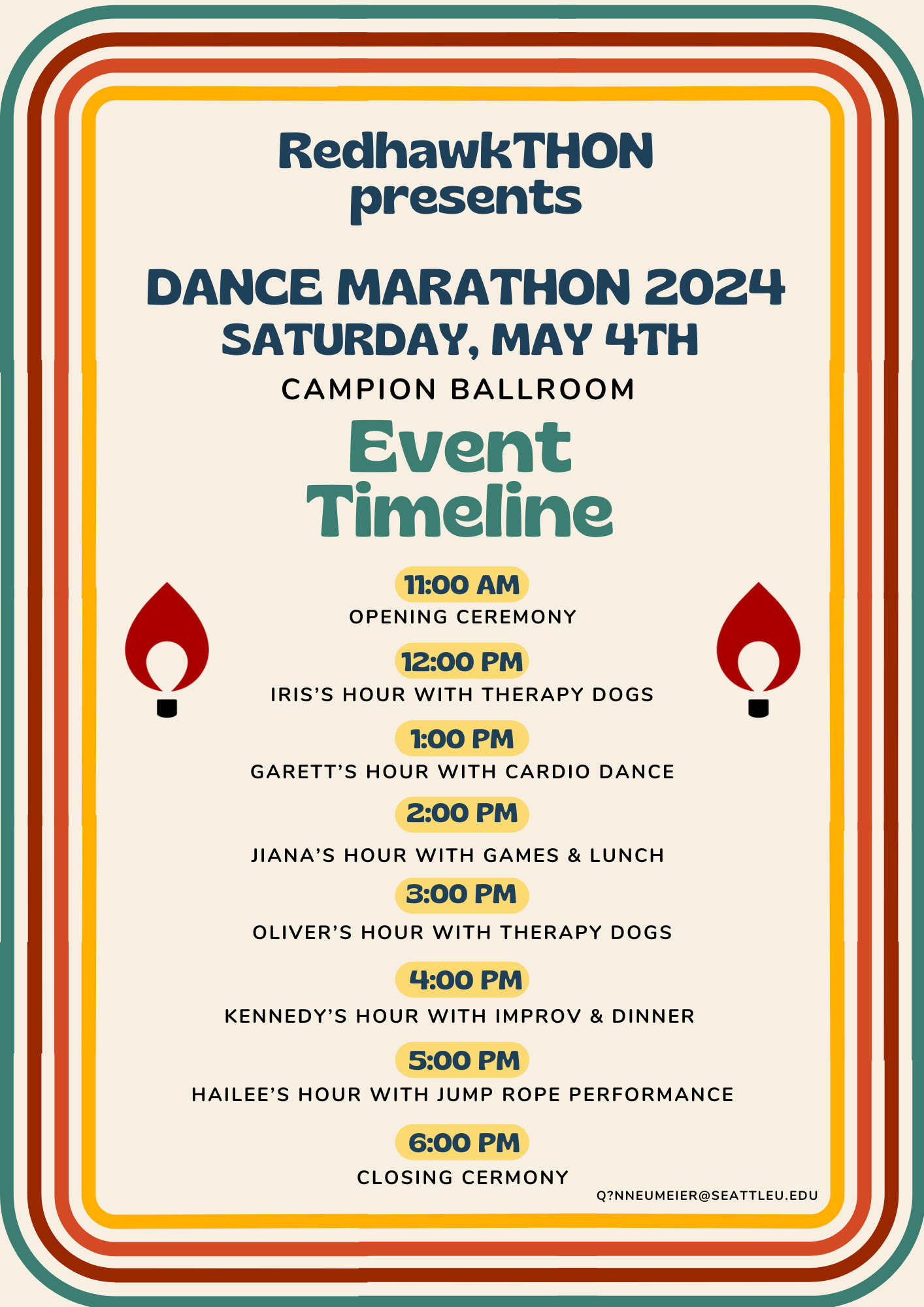

All faculty and staff are welcome to stop by Campion Ballroom on Saturday, April 22, between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. in support of the annual student RedhawkTHON's Dance Marathon.

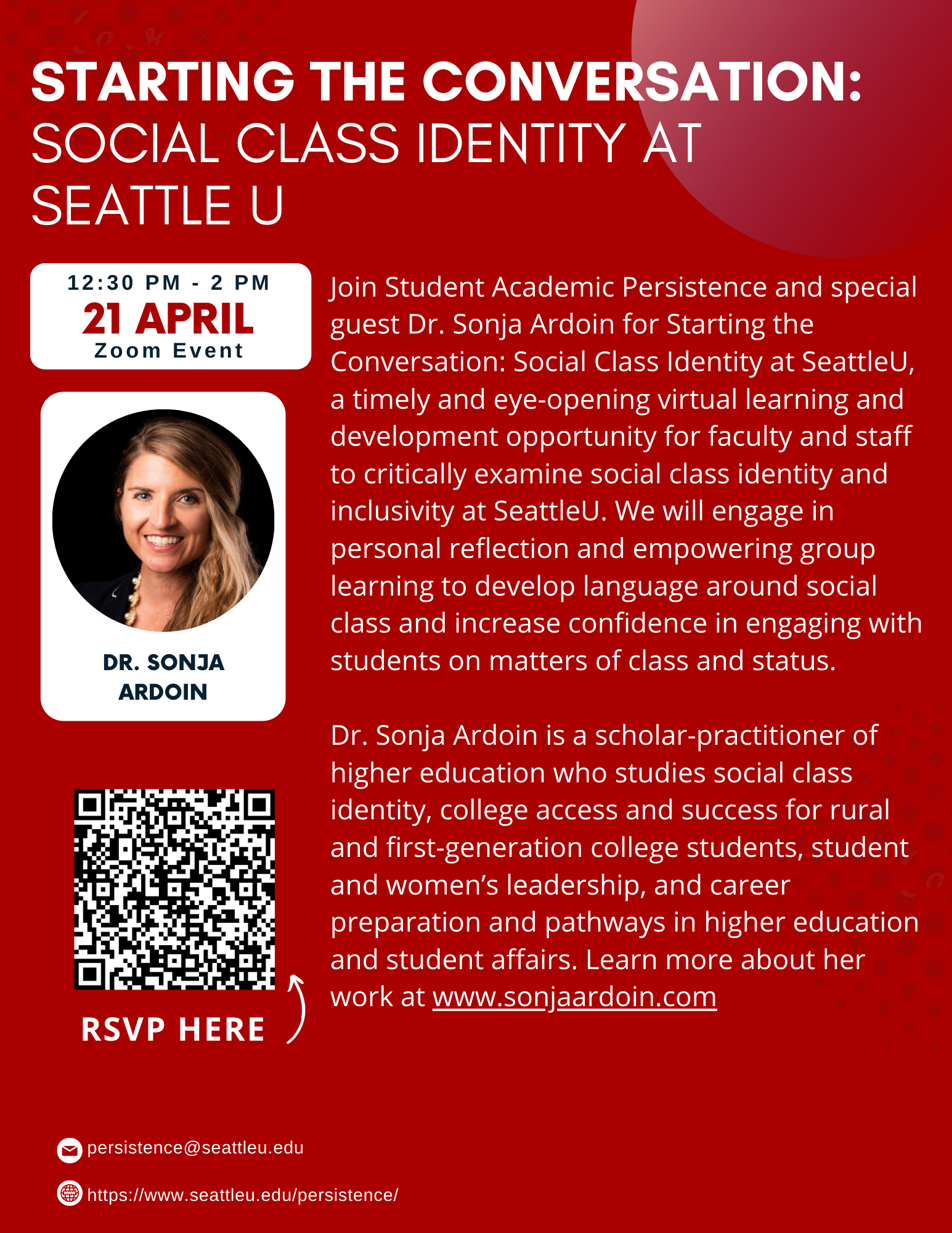

All faculty and staff are welcome to stop by Campion Ballroom on Saturday, April 22, between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. in support of the annual student RedhawkTHON's Dance Marathon. Friday, April 21

Friday, April 21

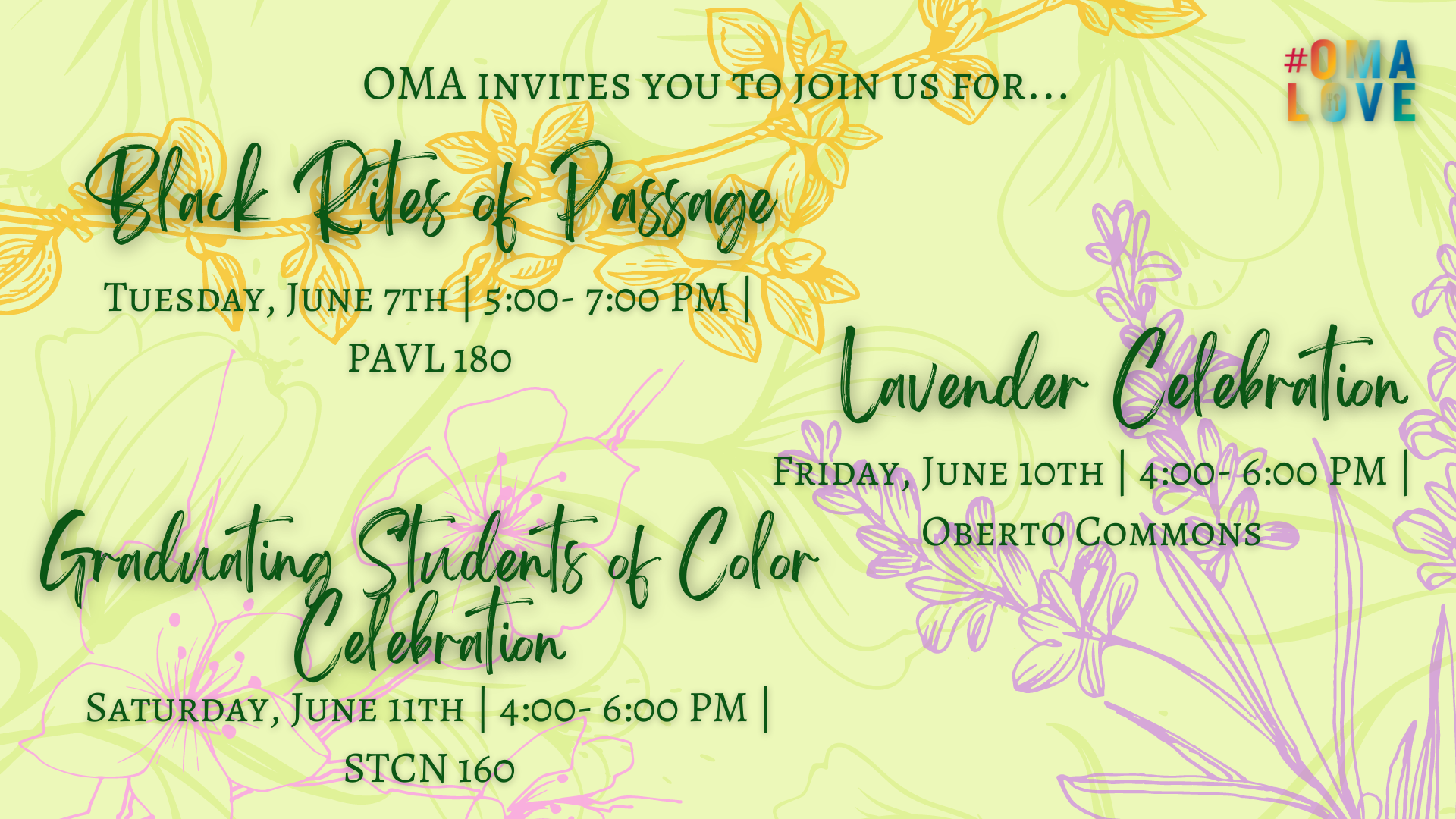

The Center for Student Involvement is excited to announce that nominations for Red Night Out, Shine Awards, Graduating Students of Color, Ignatian Leaders, Lavender Celebration and International Student Graduation Reception are now open.

The Center for Student Involvement is excited to announce that nominations for Red Night Out, Shine Awards, Graduating Students of Color, Ignatian Leaders, Lavender Celebration and International Student Graduation Reception are now open.

Pope Francis said, “Work is a necessity, part of the meaning of life on this earth, a path to growth, human development and personal fulfillment.” What does it mean to value work and workers here at Seattle University? Join your colleagues for lunch, meaningful reflection and stimulating conversation on the connection between our Jesuit Catholic mission and the dignity of work and workers.

Pope Francis said, “Work is a necessity, part of the meaning of life on this earth, a path to growth, human development and personal fulfillment.” What does it mean to value work and workers here at Seattle University? Join your colleagues for lunch, meaningful reflection and stimulating conversation on the connection between our Jesuit Catholic mission and the dignity of work and workers.

Monday, April 17, noon–2 p.m.

Monday, April 17, noon–2 p.m..jpeg)

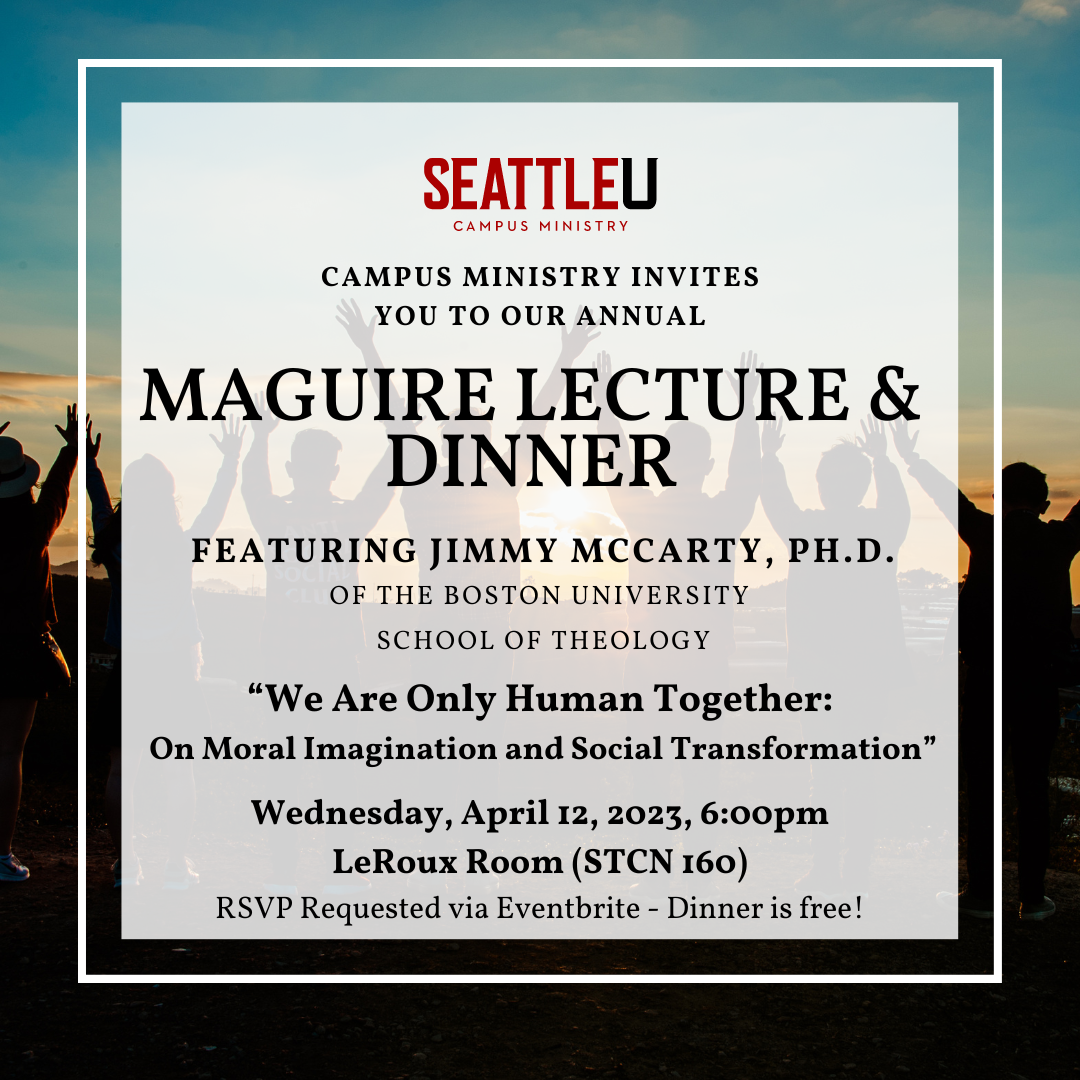

Wednesday, April 12, 6–8:30 p.m.

Wednesday, April 12, 6–8:30 p.m.

Friday, April 21, noon–1:30 p.m.

Friday, April 21, noon–1:30 p.m. The

The

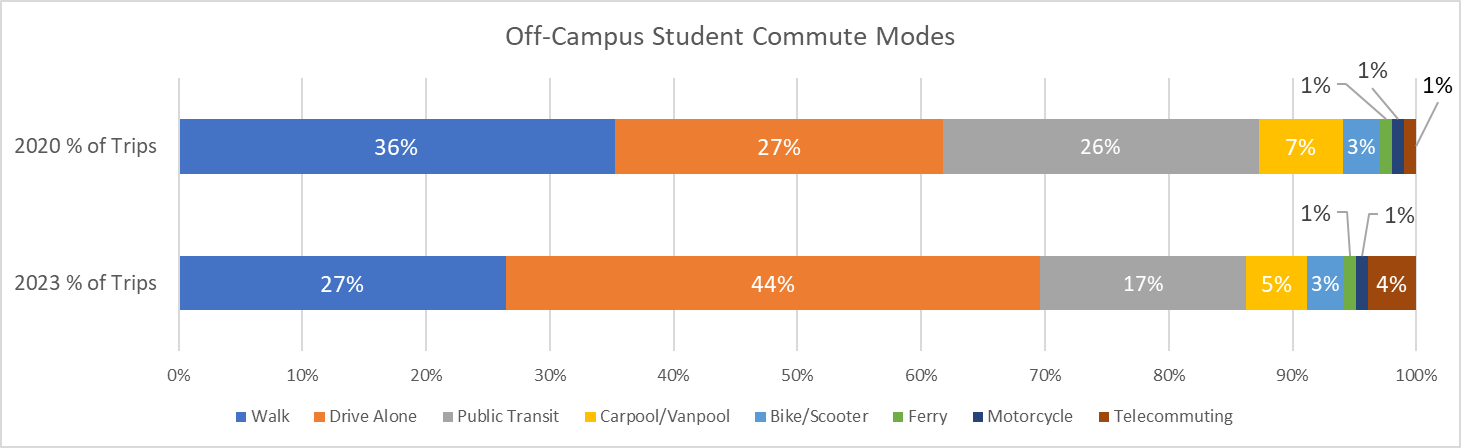

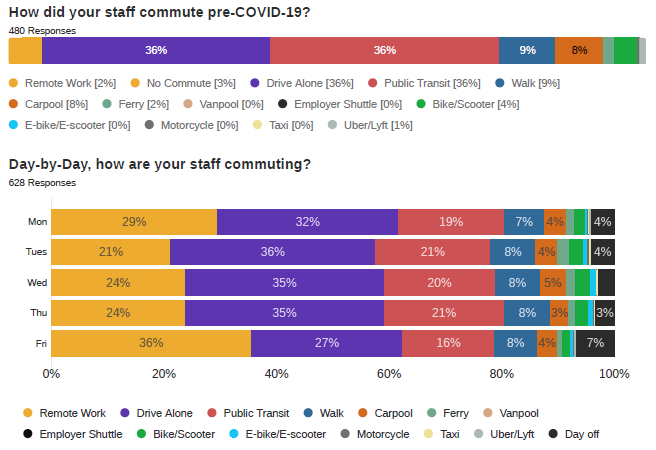

Thank you to all who have participated so far in the campus-wide commuting survey! If you haven’t taken the survey yet, a reminder email will be sent to you today. May we ask you to take about 10 minutes of your time to complete the questionnaire. Your input is much appreciated.

Thank you to all who have participated so far in the campus-wide commuting survey! If you haven’t taken the survey yet, a reminder email will be sent to you today. May we ask you to take about 10 minutes of your time to complete the questionnaire. Your input is much appreciated.

Photo by Lucas Peltier/WAC

Photo by Lucas Peltier/WAC Seattle University is excited to announce ceremony times for the 2023 Seattle University Commencement at Climate Pledge Arena on Monday, June 12!

Seattle University is excited to announce ceremony times for the 2023 Seattle University Commencement at Climate Pledge Arena on Monday, June 12!

.png)

Photo by Sarah Finney

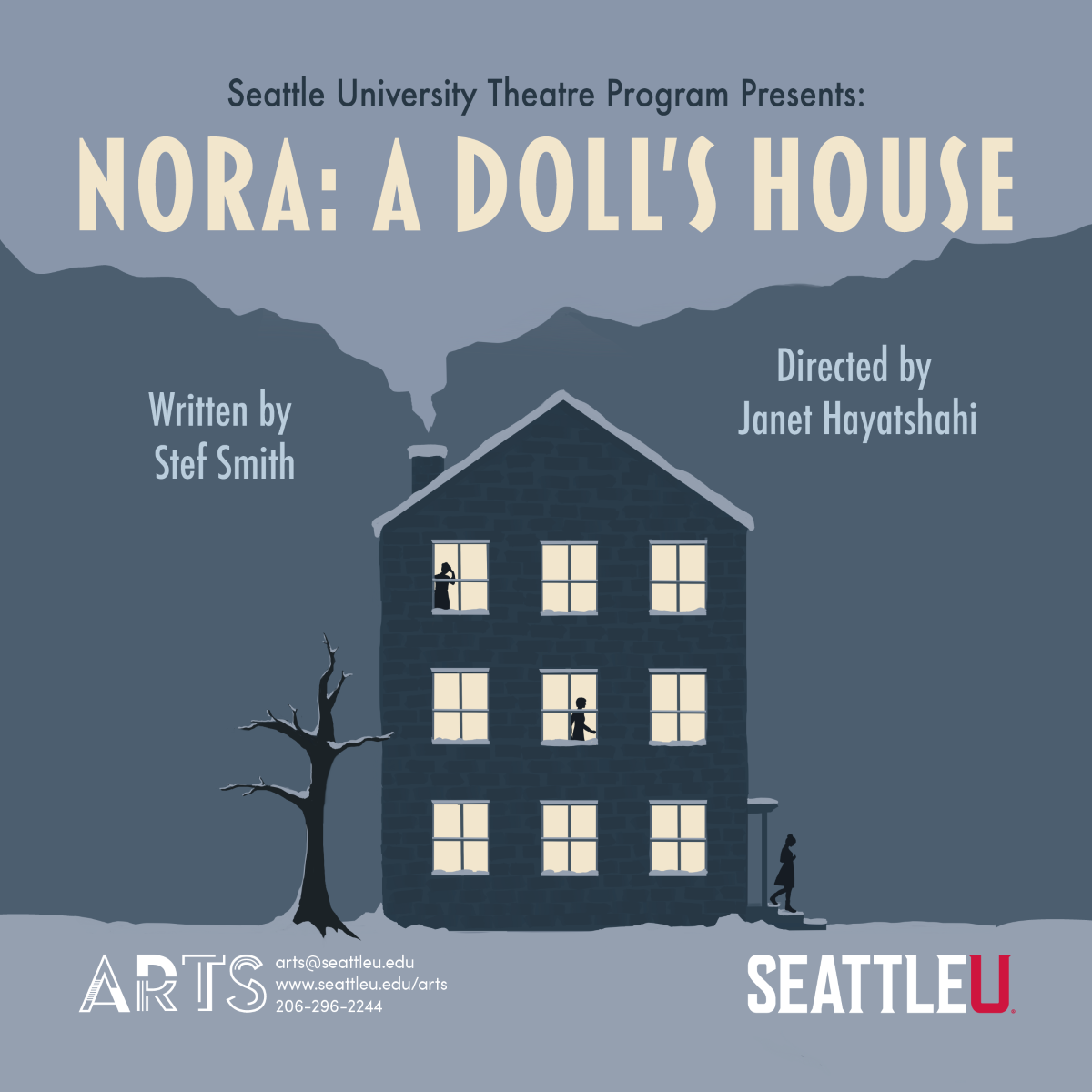

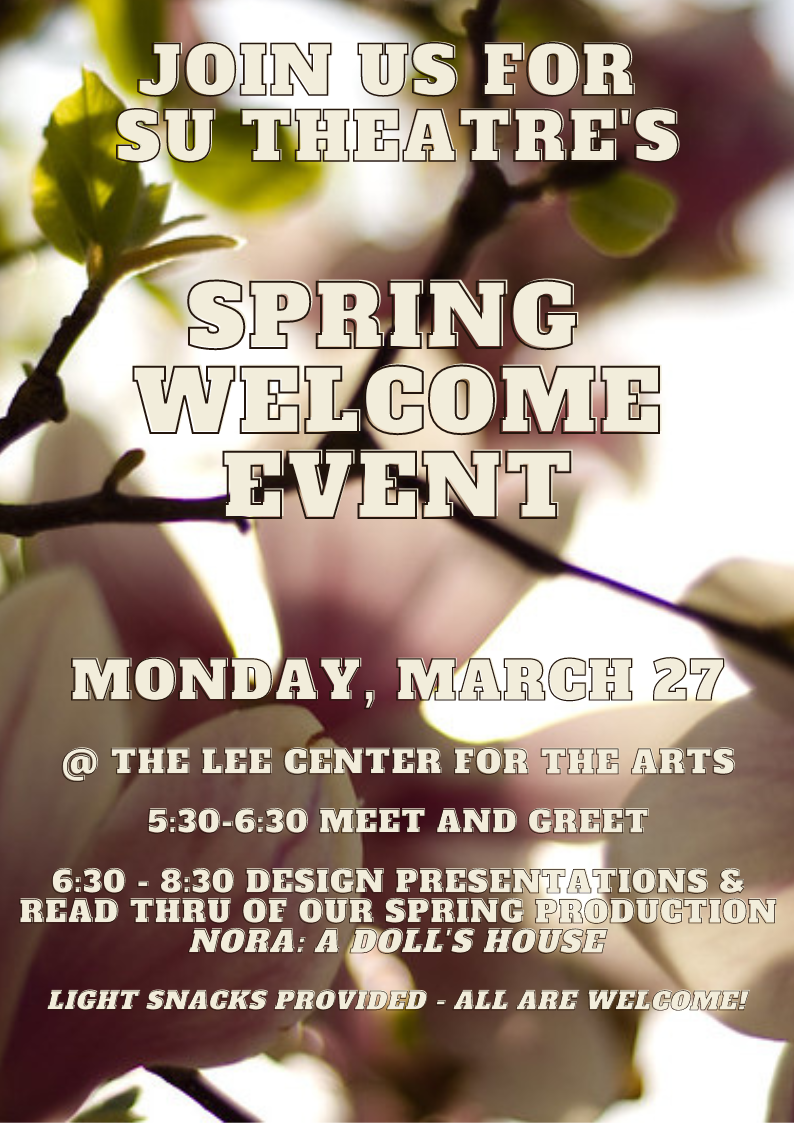

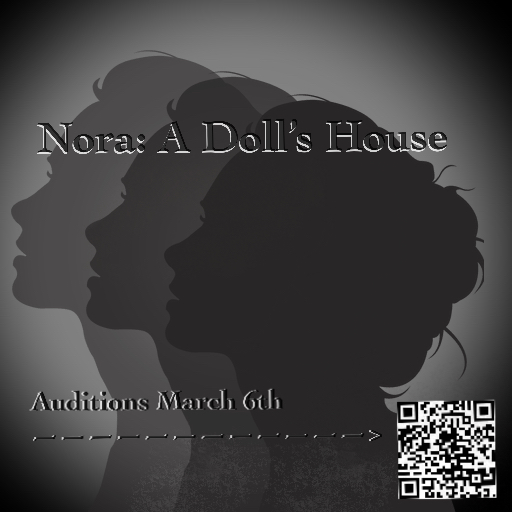

Photo by Sarah Finney Students and faculty are welcome to audition for Nora: A Doll’s House, a modern re-telling by Stef Smith of A Doll’s House, written by Henrik Ibsen in 1879. The play follows Nora in three different time periods, contemplating their options during eras when radical shifts were taking place in women’s rights.

Students and faculty are welcome to audition for Nora: A Doll’s House, a modern re-telling by Stef Smith of A Doll’s House, written by Henrik Ibsen in 1879. The play follows Nora in three different time periods, contemplating their options during eras when radical shifts were taking place in women’s rights.

Listen to the podcast with Dr. Steen Halling

Listen to the podcast with Dr. Steen Halling

Photo by Sarah Finney

Photo by Sarah Finney

What will be the best tech ads at the 2023 Super Bowl?

What will be the best tech ads at the 2023 Super Bowl?

Update – Jan. 31, 2023:

Update – Jan. 31, 2023:

Wednesday, Feb. 15, 4-5:30 p.m.

Wednesday, Feb. 15, 4-5:30 p.m.

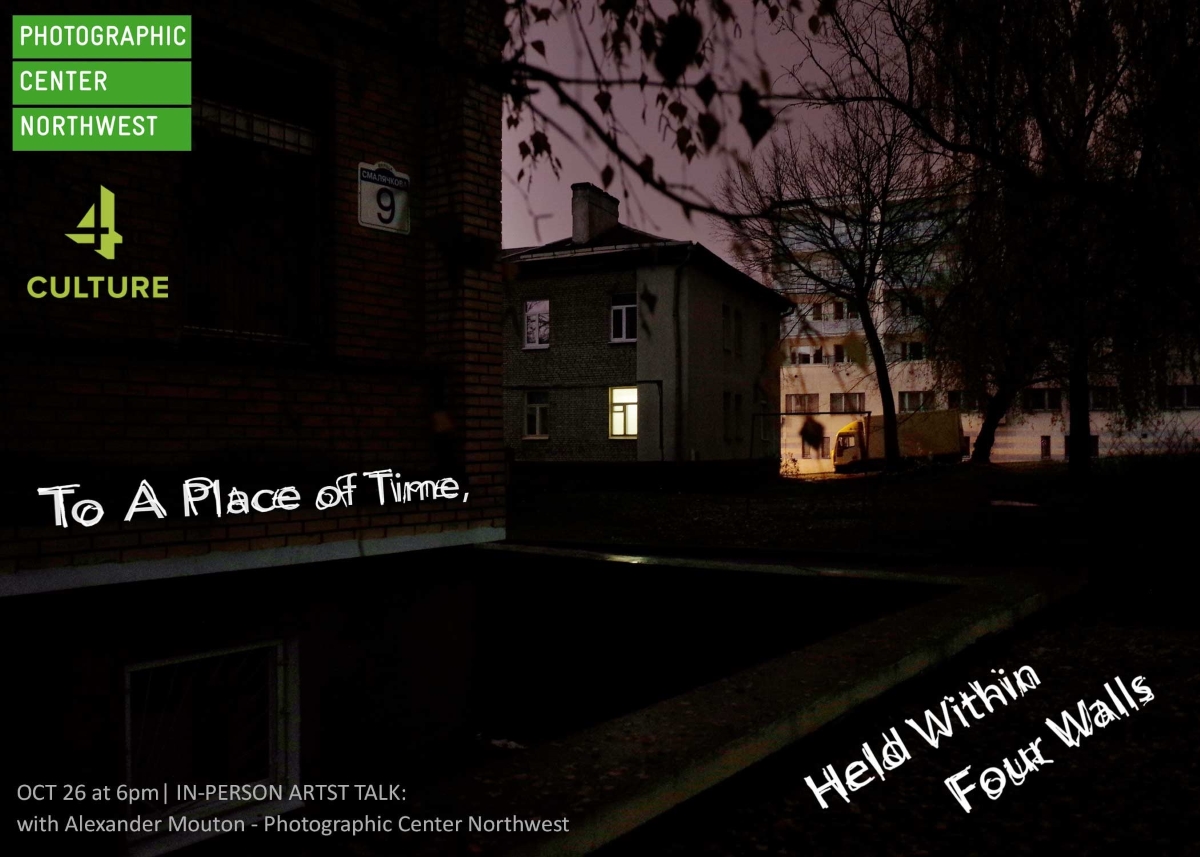

Thursday, Feb. 9, 4 p.m. (public reception at 3:15 p.m.)

Thursday, Feb. 9, 4 p.m. (public reception at 3:15 p.m.).jpg)

11th Annual Go Move Challenge Starts Feb. 1

11th Annual Go Move Challenge Starts Feb. 1

.png)

Tuesday, Jan. 17, 6:30 p.m.

Tuesday, Jan. 17, 6:30 p.m.

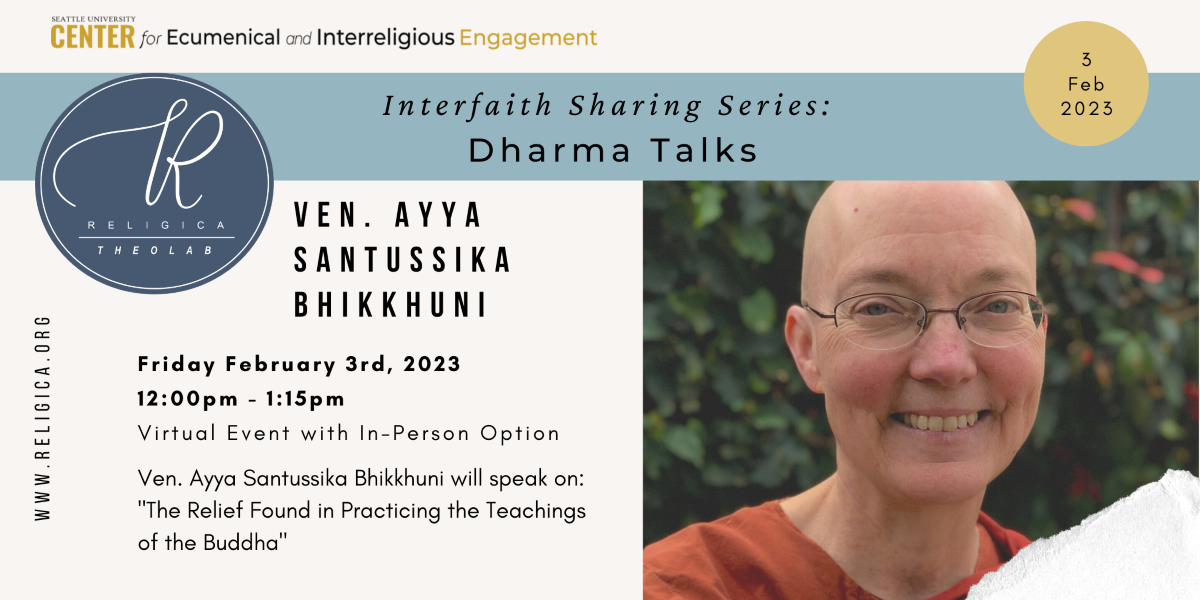

*Friday, Feb. 3–Sunday, Feb. 5

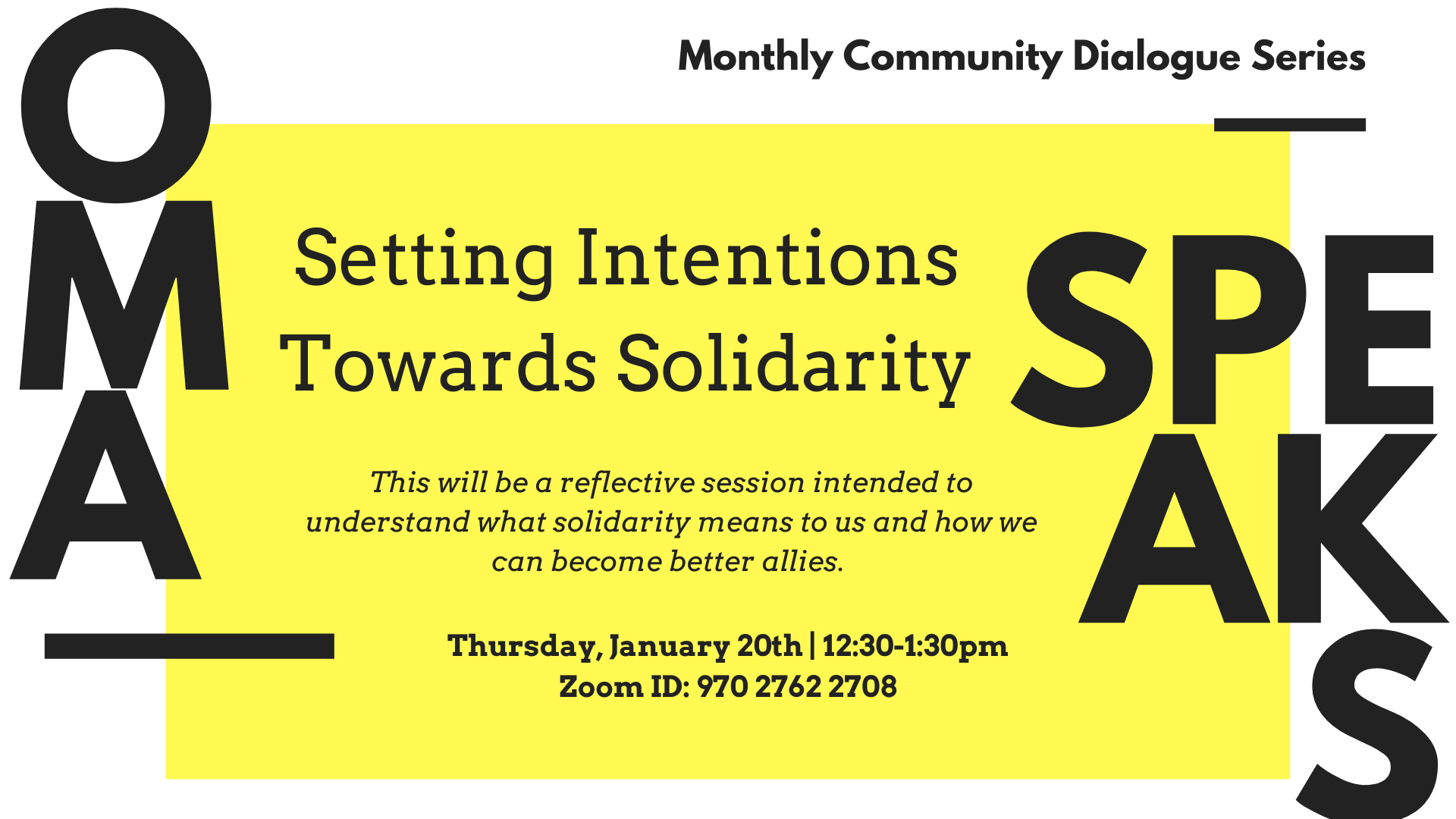

*Friday, Feb. 3–Sunday, Feb. 5 Thursday, Jan. 19, 12:30-1:30 p.m.

Thursday, Jan. 19, 12:30-1:30 p.m.

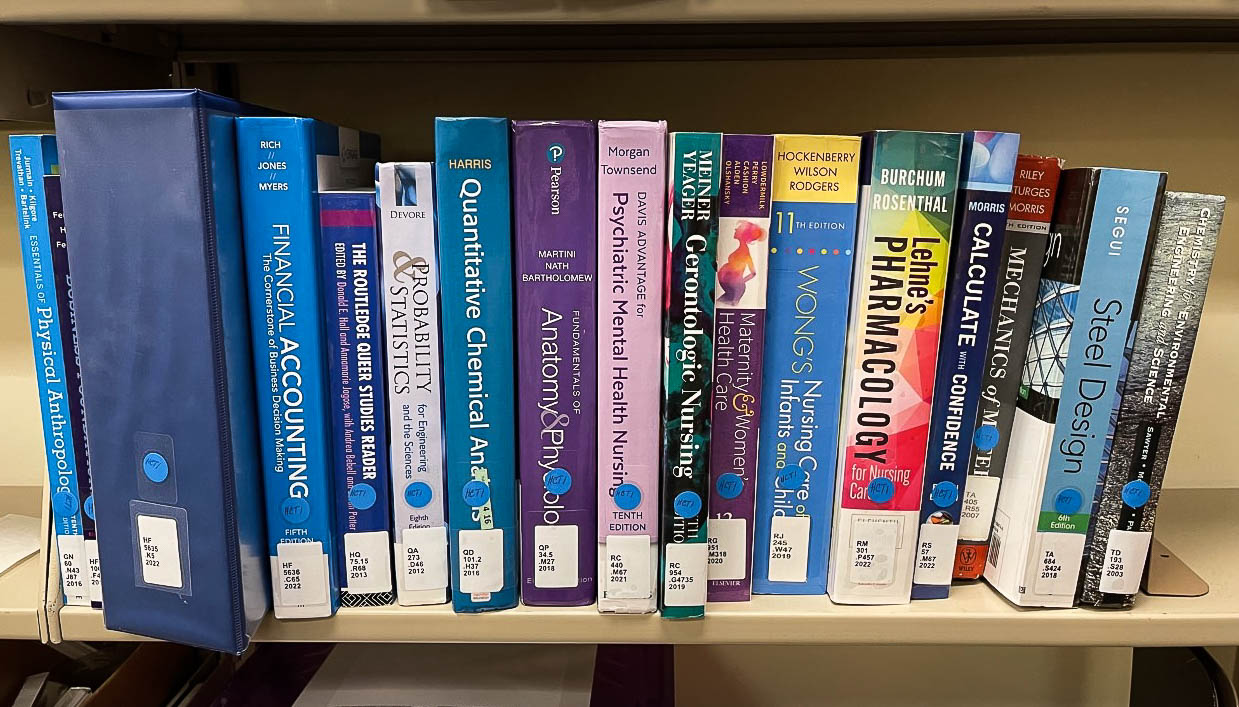

Photo by Andrew Khauv

Photo by Andrew Khauv By Jacob Smithers, Lemieux Library and McGoldrick Learning Commons

By Jacob Smithers, Lemieux Library and McGoldrick Learning Commons

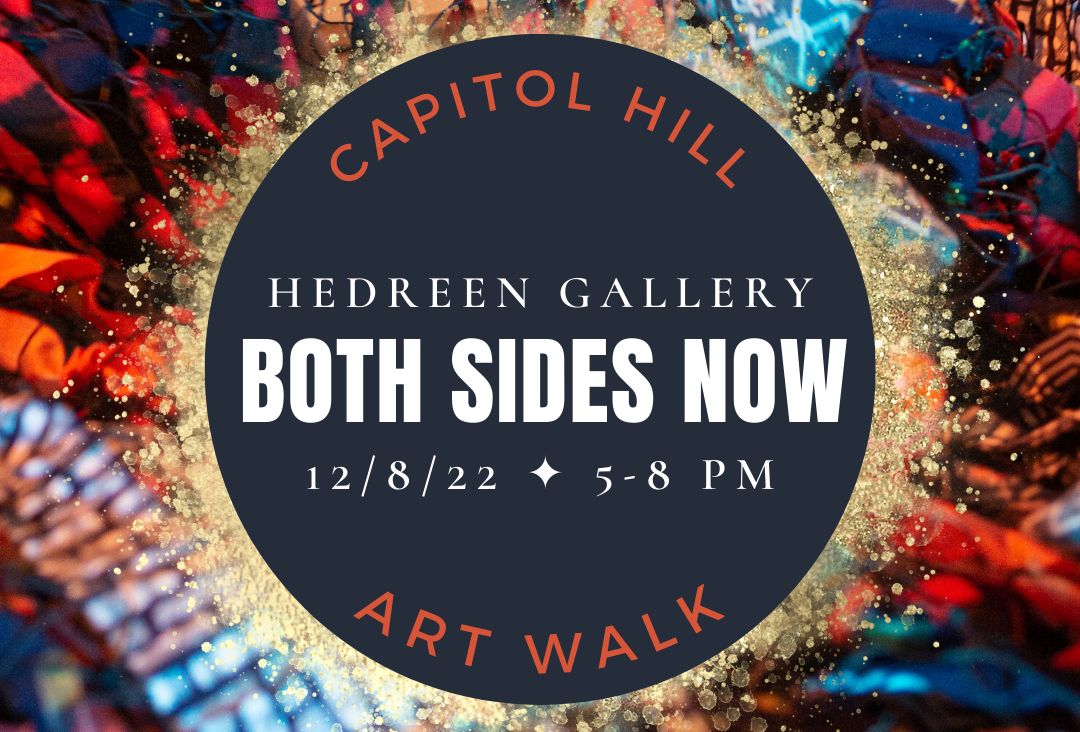

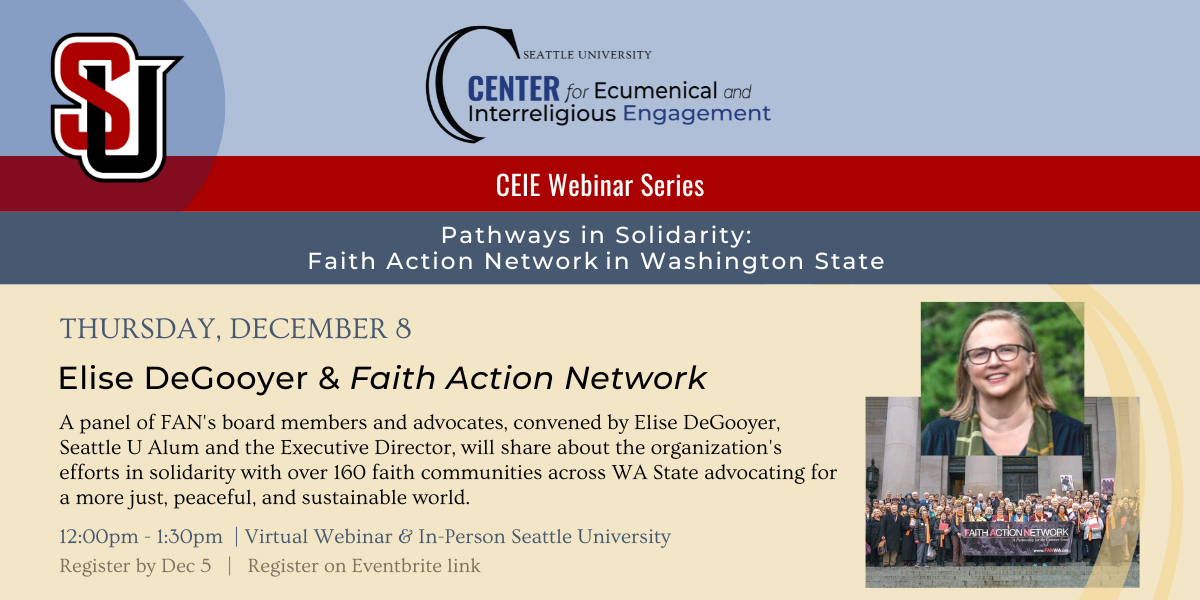

Thursday, Dec. 8, noon–1 p.m.

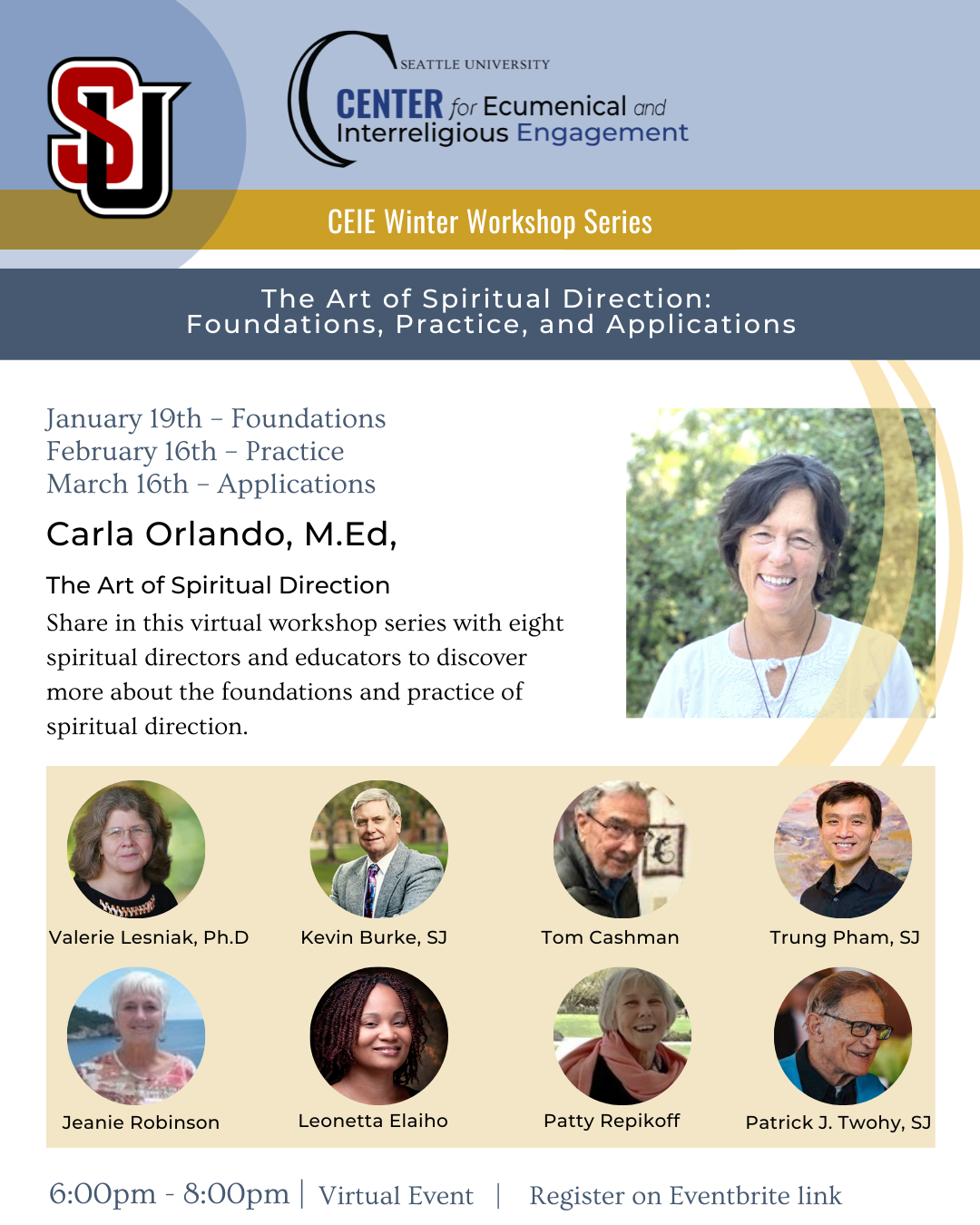

Thursday, Dec. 8, noon–1 p.m. On-campus Gatherings: Thursdays, Jan. 19 and 26, Feb. 2 and 16

On-campus Gatherings: Thursdays, Jan. 19 and 26, Feb. 2 and 16

Photo by Sarah Finney

Photo by Sarah Finney

Wednesday, Nov. 16

Wednesday, Nov. 16

Photo by Aaron K. Libed

Photo by Aaron K. Libed

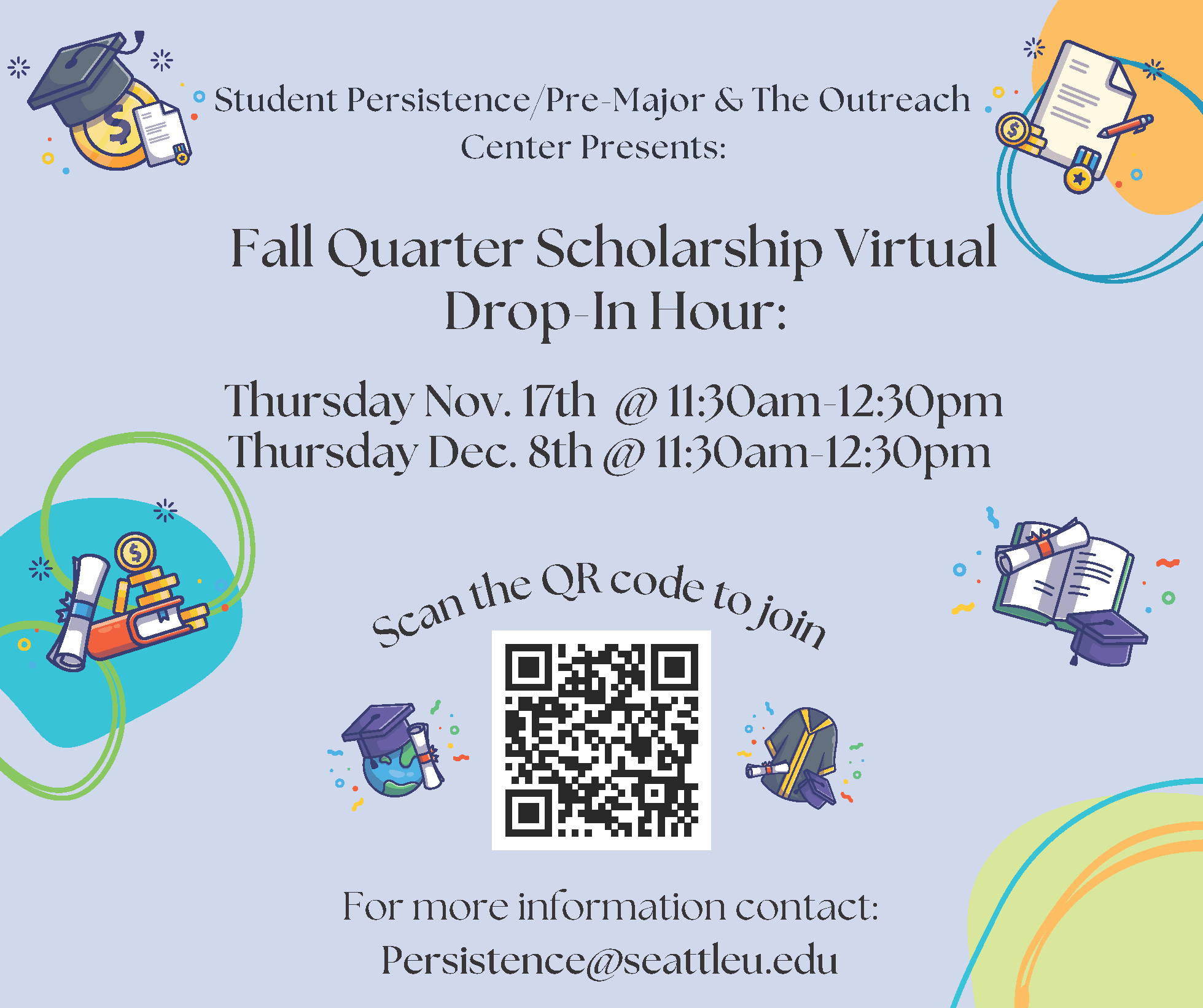

Thursday, Nov. 17, noon-1 p.m.

Thursday, Nov. 17, noon-1 p.m.

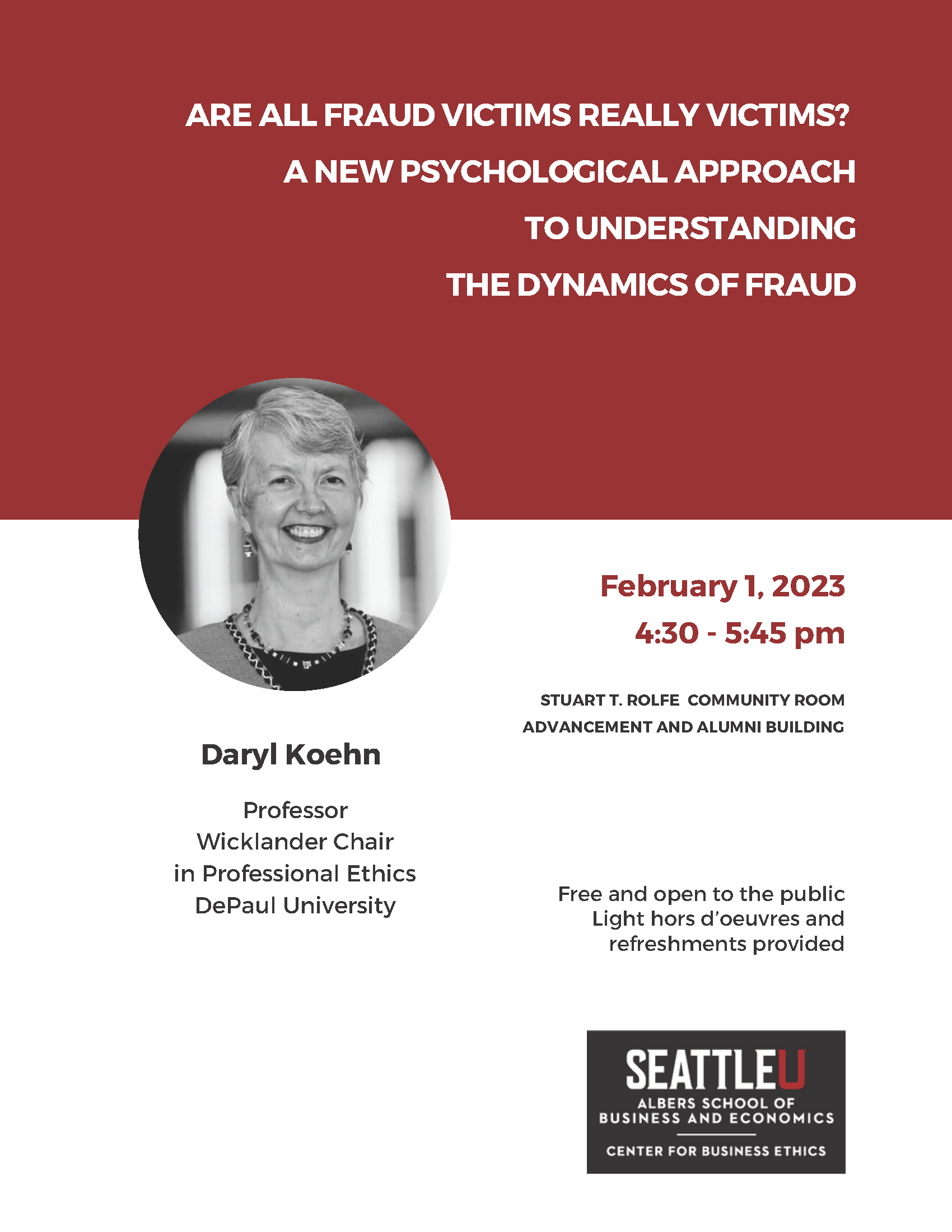

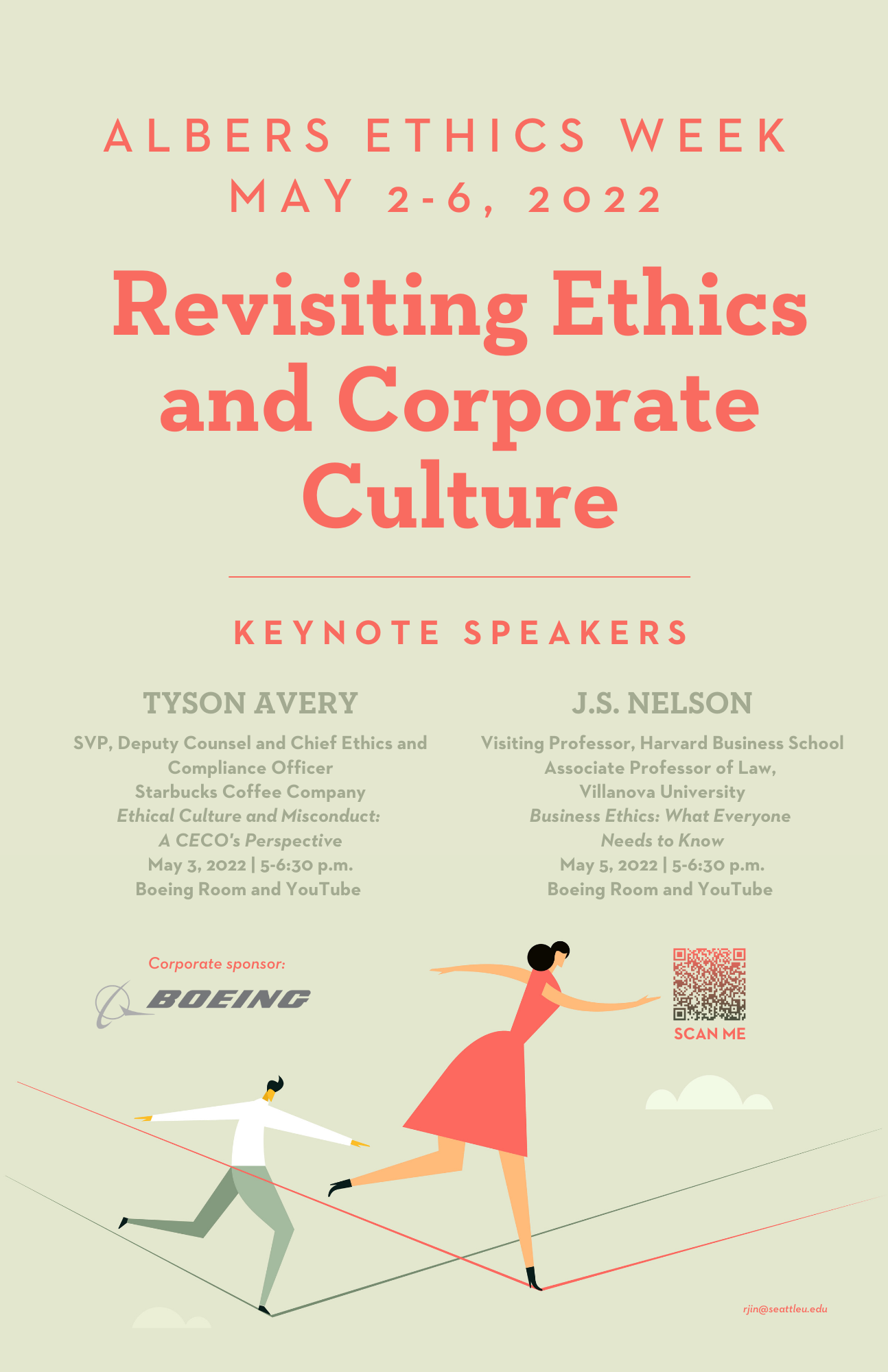

Loyola University Chicago Professor of Business Ethics Abraham Singer will discuss issues at the intersection of responsible

Loyola University Chicago Professor of Business Ethics Abraham Singer will discuss issues at the intersection of responsible

-cropped.jpg)

.png)

A Midweek Pause: Soul Sessions

A Midweek Pause: Soul Sessions

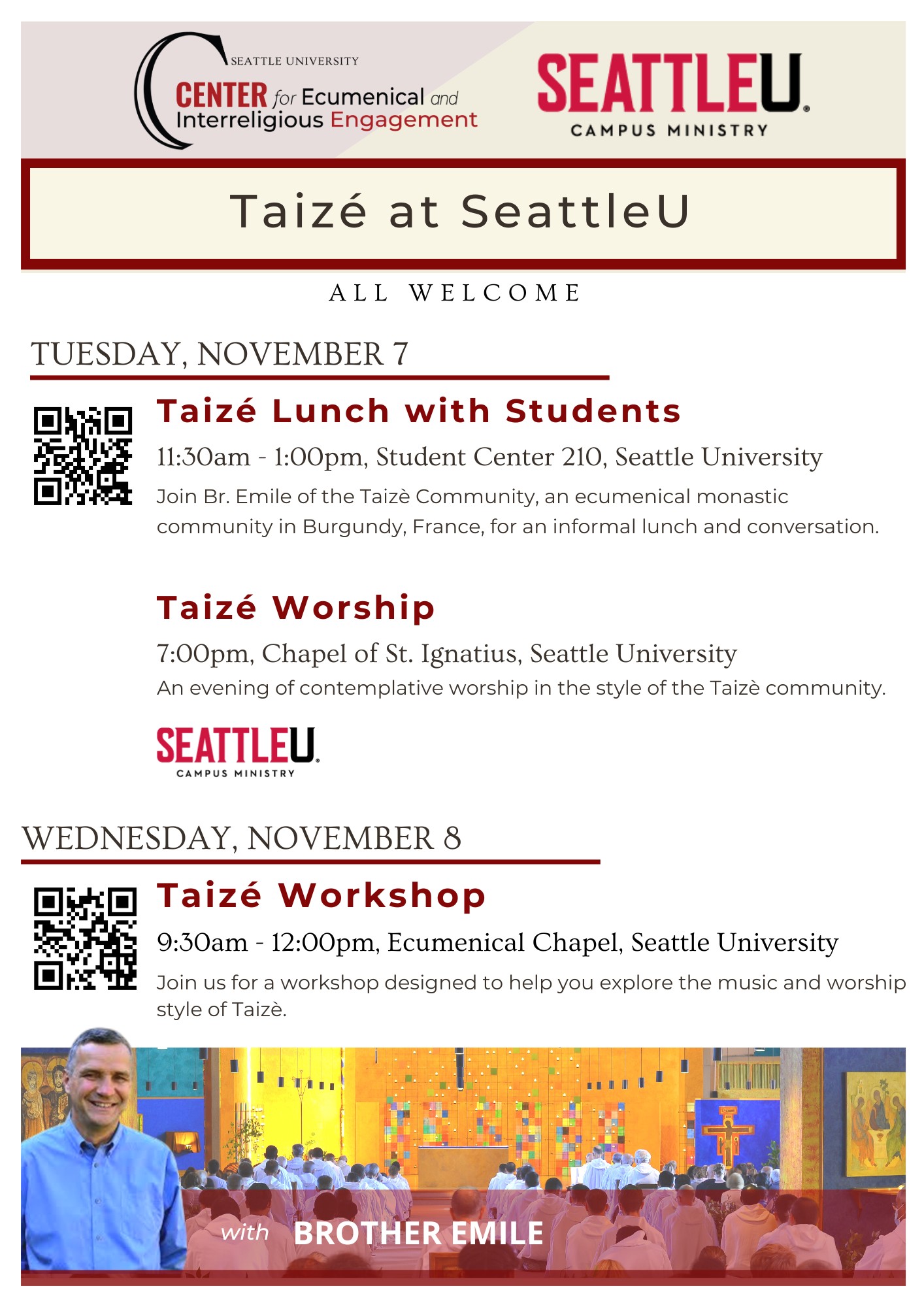

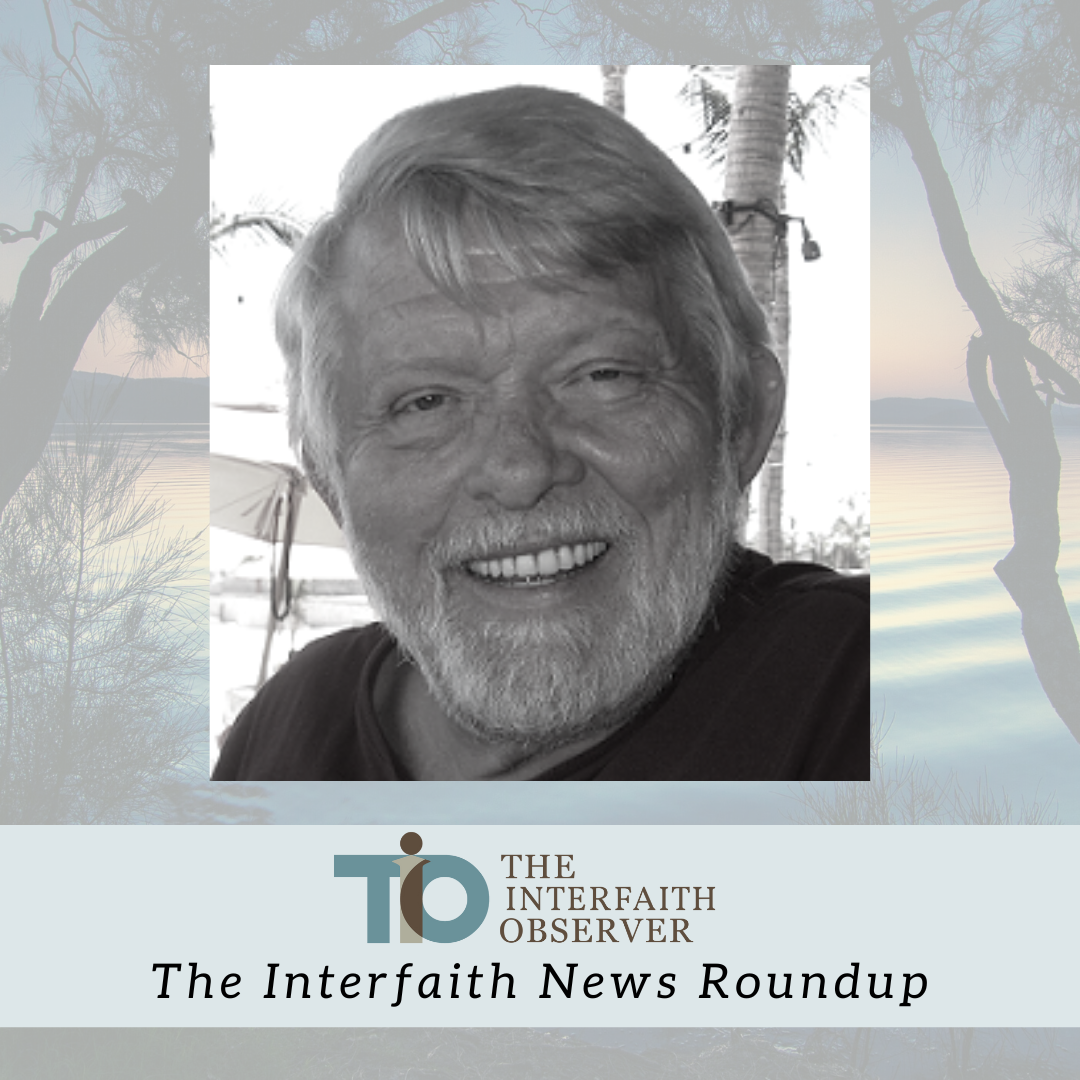

The Interfaith News Roundup is an aggregator of important religion and spirituality news in the world. It is a monthly feature in The Interfaith Observer since 2011 and today is at home in The Center for Ecumenical and Interreligious Engagement (CEIE) at Seattle University.

The Interfaith News Roundup is an aggregator of important religion and spirituality news in the world. It is a monthly feature in The Interfaith Observer since 2011 and today is at home in The Center for Ecumenical and Interreligious Engagement (CEIE) at Seattle University.

Serving in theological education for nearly forty years, Rev. Dr. Molly T. Marshall believes she was put on the earth to love students, teach theology, guide spiritual formation and challenge patriarchal structures that would hinder women from full acceptance in all forms of ministry. She has worked as a youth minister, campus minister, pastor, scholar and theological educator, seeking to dismantle all forms of oppression.

Serving in theological education for nearly forty years, Rev. Dr. Molly T. Marshall believes she was put on the earth to love students, teach theology, guide spiritual formation and challenge patriarchal structures that would hinder women from full acceptance in all forms of ministry. She has worked as a youth minister, campus minister, pastor, scholar and theological educator, seeking to dismantle all forms of oppression. Rev. Paul Chaffee (pictured) is the founder of The Interfaith Observer (TIO). He was the founding executive director of the Interfaith Center at the Presidio, serving for 17 years. He sat on the United Religions Initiative’s original Board of Directors for six years, was a trustee of the North American Interfaith Network (NAIN) for ten, and was a Parliament Ambassador for the Parliament of the World’s Religions for three.

Rev. Paul Chaffee (pictured) is the founder of The Interfaith Observer (TIO). He was the founding executive director of the Interfaith Center at the Presidio, serving for 17 years. He sat on the United Religions Initiative’s original Board of Directors for six years, was a trustee of the North American Interfaith Network (NAIN) for ten, and was a Parliament Ambassador for the Parliament of the World’s Religions for three.

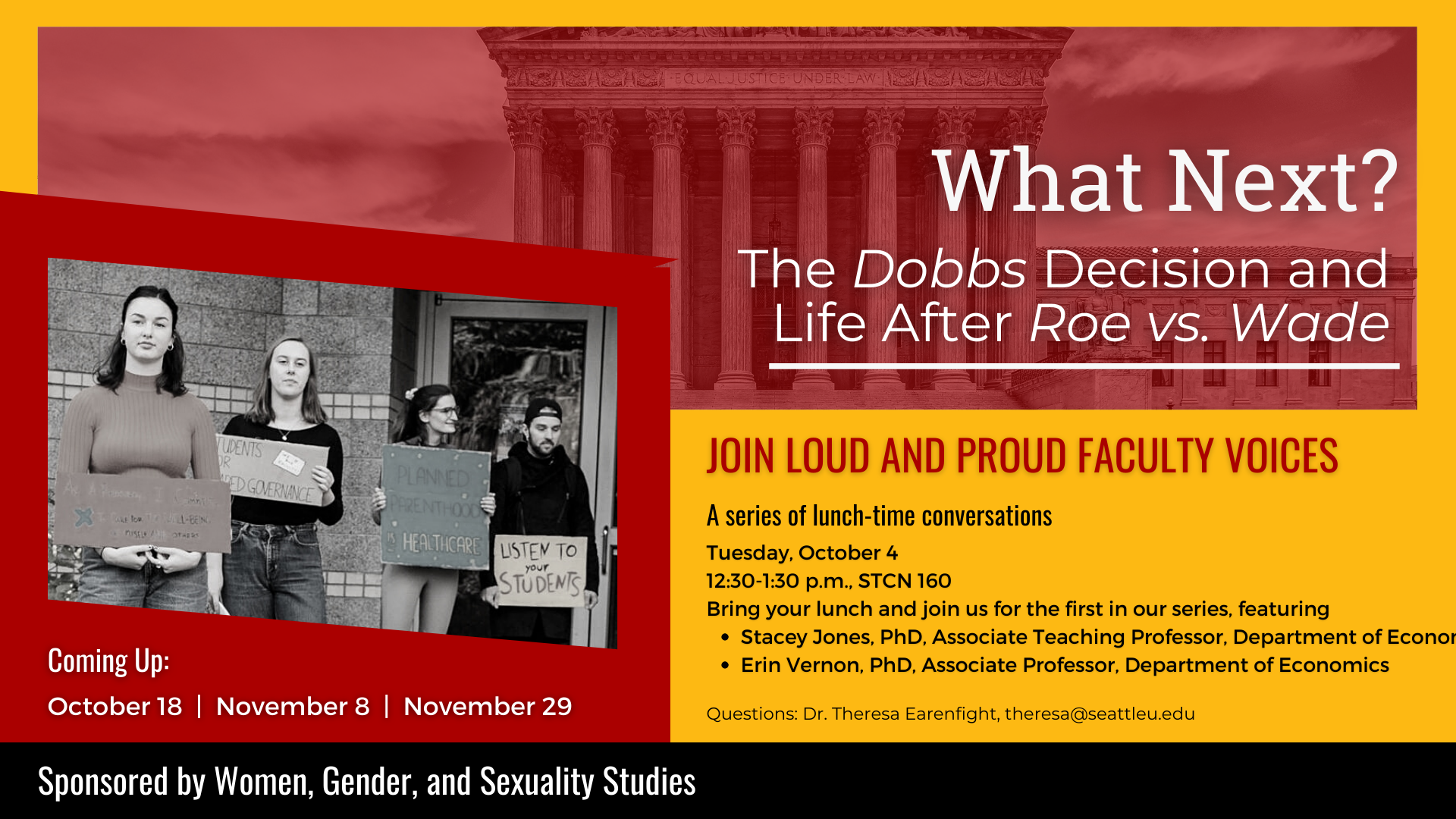

Tuesday, Oct. 4, noon-1:30 p.m.

Tuesday, Oct. 4, noon-1:30 p.m.

On Sept. 15, we remembered, mourned and reflected on the horrific bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., that took place 59 years ago. We remember Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley, the four young girls who were killed in the racially motivated attack.

On Sept. 15, we remembered, mourned and reflected on the horrific bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., that took place 59 years ago. We remember Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley, the four young girls who were killed in the racially motivated attack.

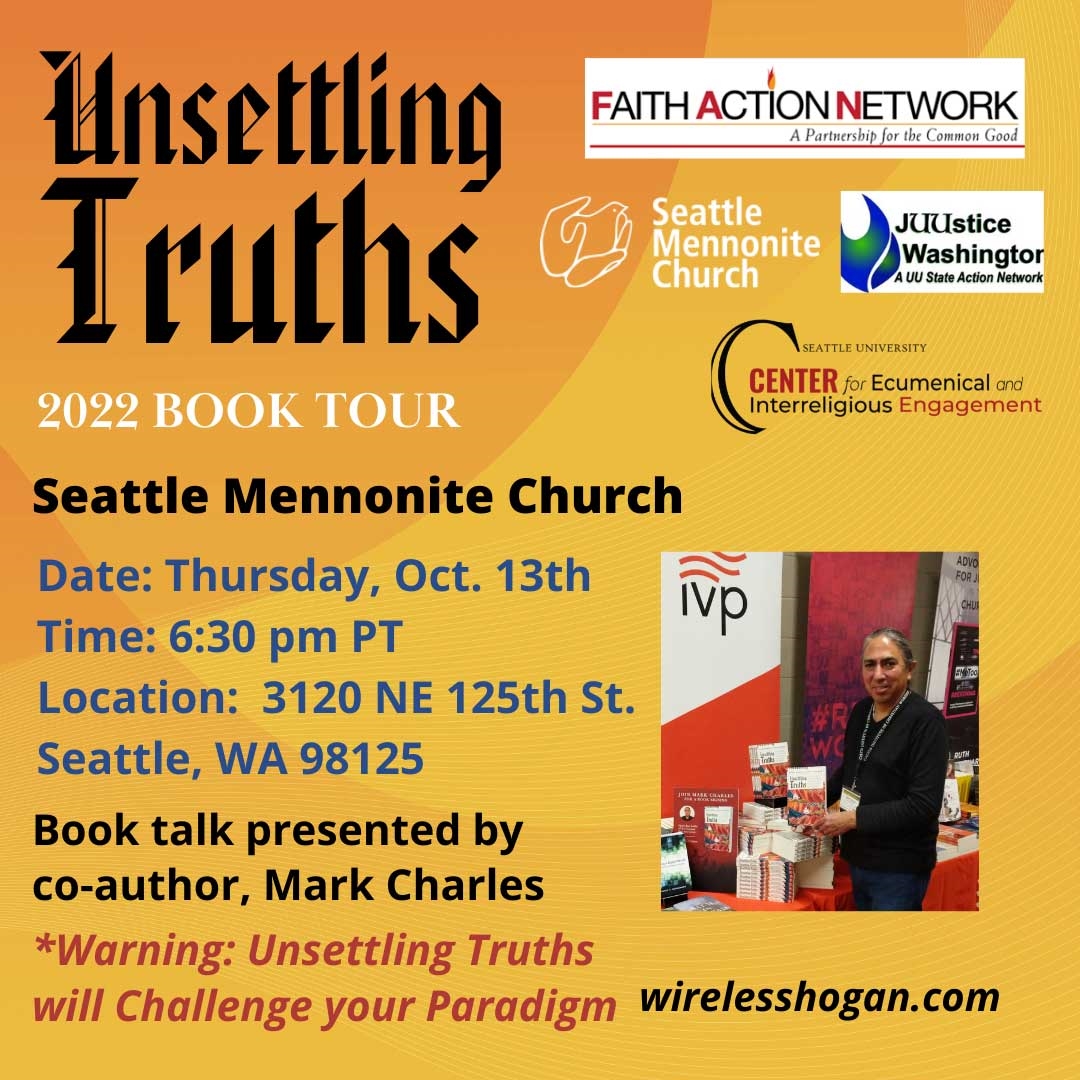

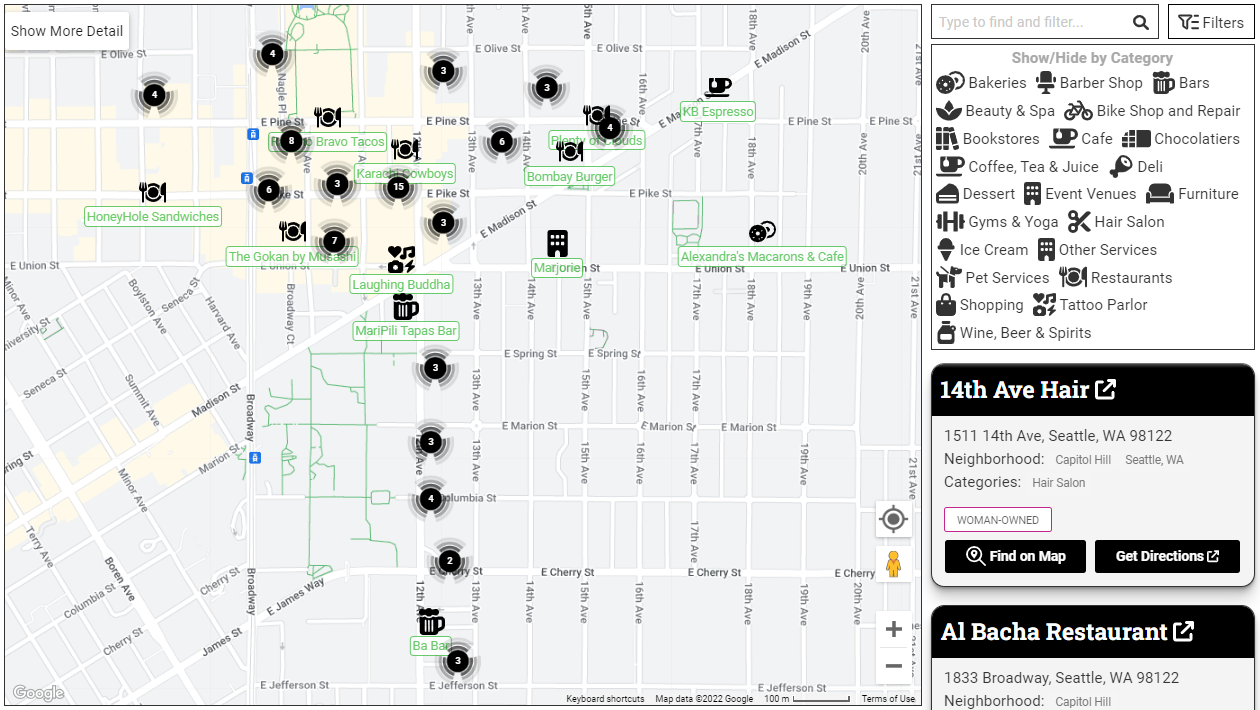

Seattle University has committed to increasing the diversity of our vendors to spend more procurement funds with diverse businesses (woman-, Black-, Indigenous-, Person of Color-, veteran- or LGBTQ-owned). Resources are available to help SU purchasers identify and purchase from diverse vendors! Visit

Seattle University has committed to increasing the diversity of our vendors to spend more procurement funds with diverse businesses (woman-, Black-, Indigenous-, Person of Color-, veteran- or LGBTQ-owned). Resources are available to help SU purchasers identify and purchase from diverse vendors! Visit

Friday, Sept. 23, 7 p.m.

Friday, Sept. 23, 7 p.m.

Photo by Yosef Kalinko

Photo by Yosef Kalinko

Photo by Yosef Kalinko

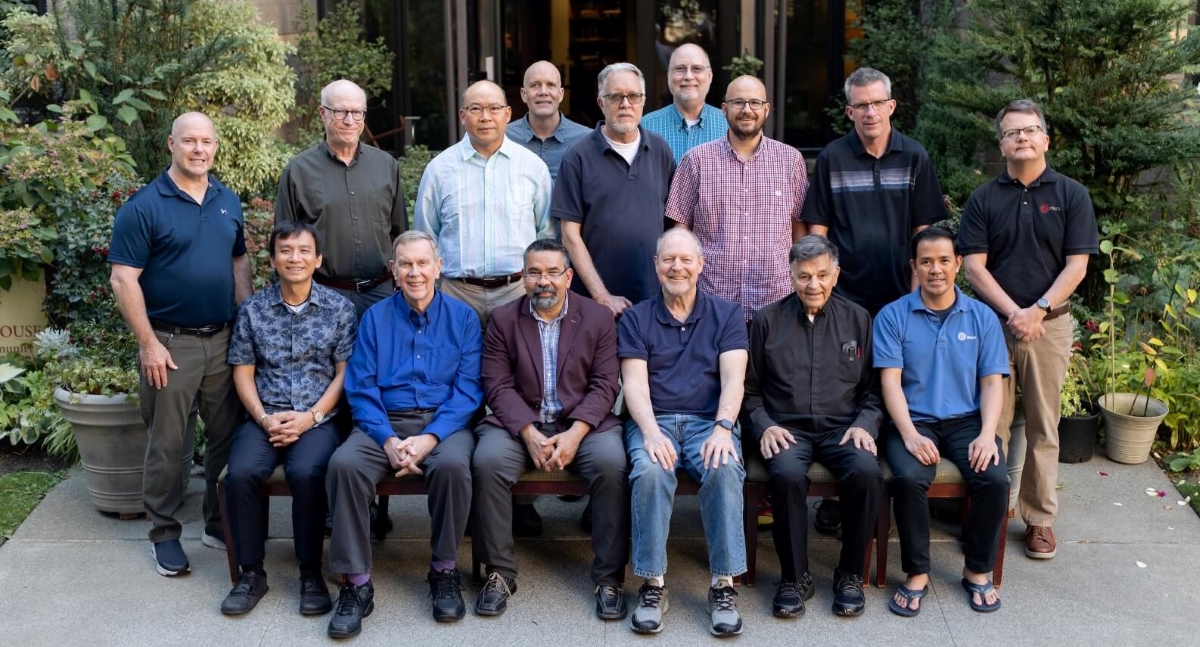

Photo by Yosef Kalinko (Re) Connecting and (Re) Committing

(Re) Connecting and (Re) Committing

Saturday, June 11, 2 p.m.

Saturday, June 11, 2 p.m.

Monday, May 23, 4 p.m.

Monday, May 23, 4 p.m.

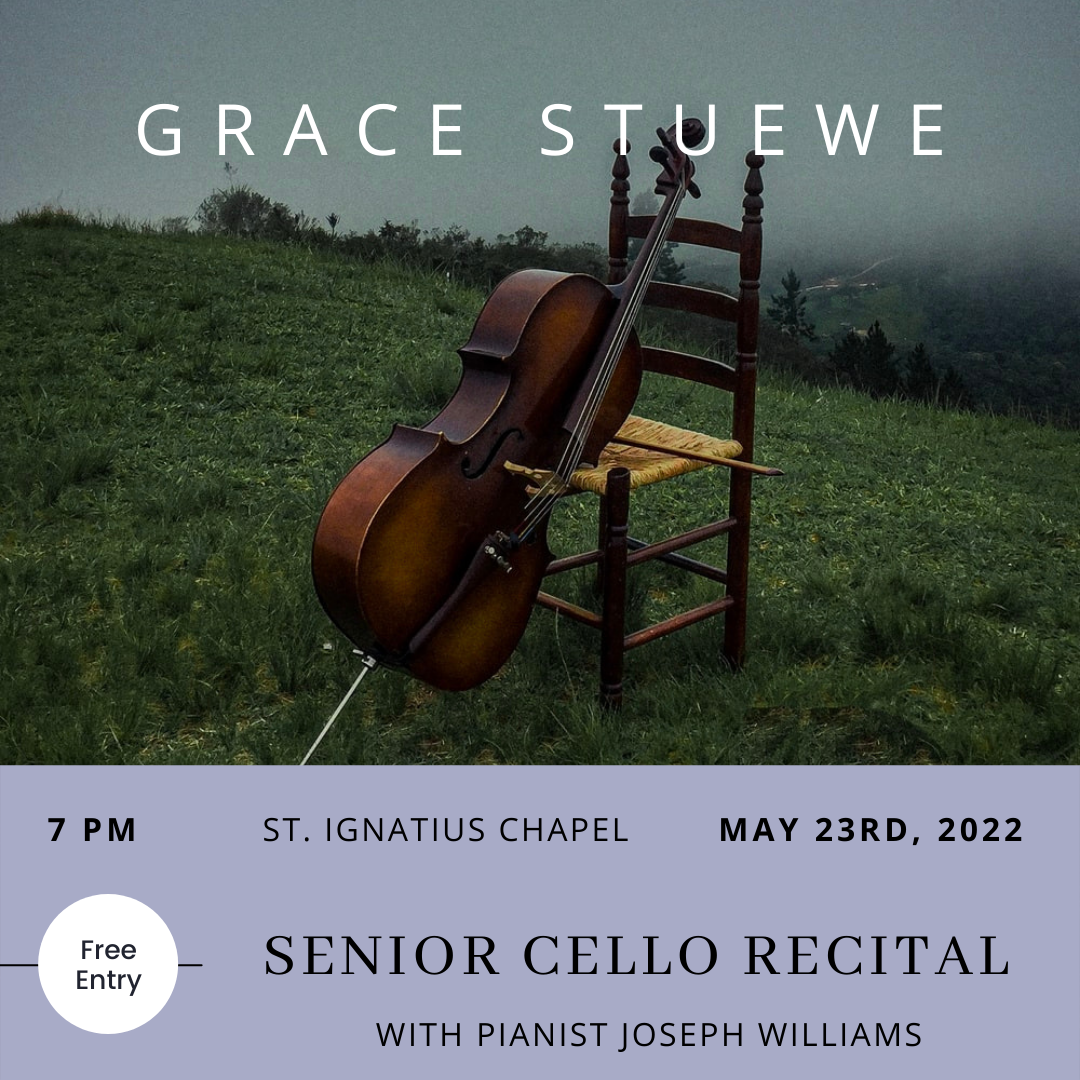

Monday, May 23, 7 p.m.

Monday, May 23, 7 p.m. You are invited to the 35th annual Projects Day on June 3.

You are invited to the 35th annual Projects Day on June 3.

Congratulations to Dr. Mo (Mo-Kyung) Sin, associate professor of nursing, on her recent award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The two-year award was funded through the NIH National Institute on Aging as part of the “Small Research Grant Program for the Next Generation of Researchers in Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias.”

Congratulations to Dr. Mo (Mo-Kyung) Sin, associate professor of nursing, on her recent award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The two-year award was funded through the NIH National Institute on Aging as part of the “Small Research Grant Program for the Next Generation of Researchers in Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias.” Wednesday, May 25, 3:30 p.m.

Wednesday, May 25, 3:30 p.m.

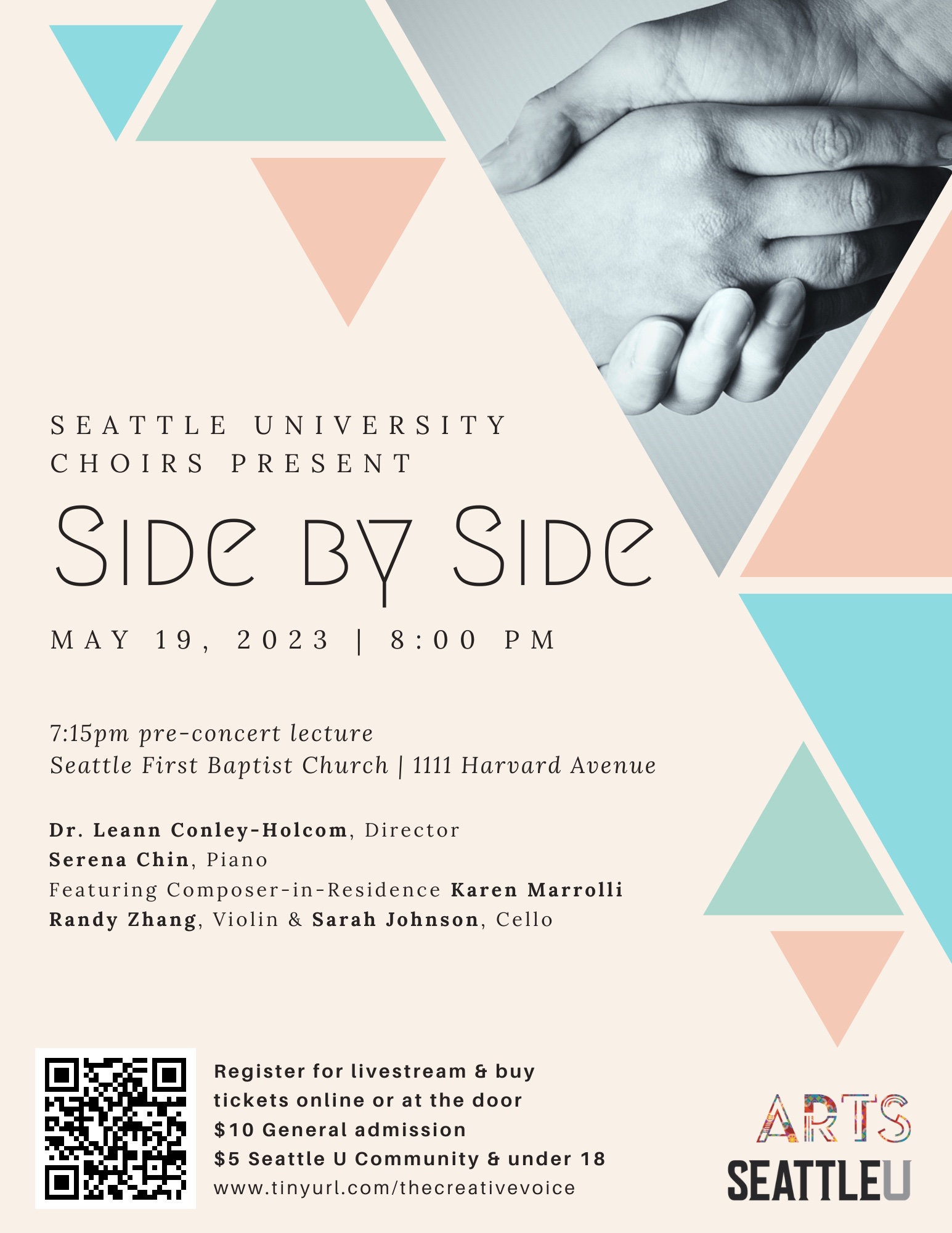

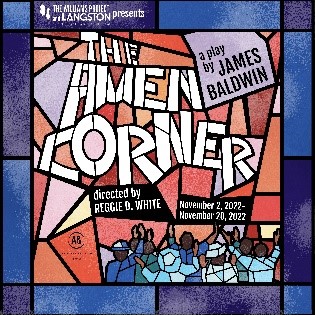

Friday, May 20, 8 p.m.

Friday, May 20, 8 p.m. Ticket prices: General Admission is $10. SU community and persons under 18: $5.

Ticket prices: General Admission is $10. SU community and persons under 18: $5.  Dear Staff Colleagues,

Dear Staff Colleagues,

John Foster, S.J., a Jesuit who served Seattle University in many capacities for three decades, passed away April 27 at the age of 88.

John Foster, S.J., a Jesuit who served Seattle University in many capacities for three decades, passed away April 27 at the age of 88. May 24, 12:30-1:20 p.m.

May 24, 12:30-1:20 p.m. Are you a student or alumni at STM, and would like to know more about the CEIE STM Student and Alumni Discernment Circle?

Are you a student or alumni at STM, and would like to know more about the CEIE STM Student and Alumni Discernment Circle?

Friday, May 13, 12:30-1:45 p.m.

Friday, May 13, 12:30-1:45 p.m.

Monday, May 16, 6:30 p.m.

Monday, May 16, 6:30 p.m.

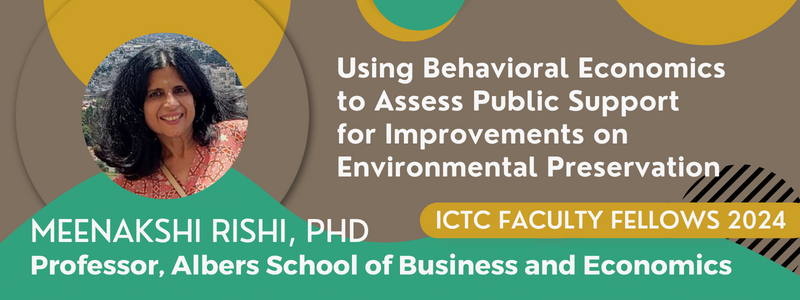

If you watch “Three Busy Debras,” you may have recognized one of the characters in a recent episode. Yes, that was Meena Rishi, professor of economics in the Albers School, making a cameo appearance on the show, which was

If you watch “Three Busy Debras,” you may have recognized one of the characters in a recent episode. Yes, that was Meena Rishi, professor of economics in the Albers School, making a cameo appearance on the show, which was

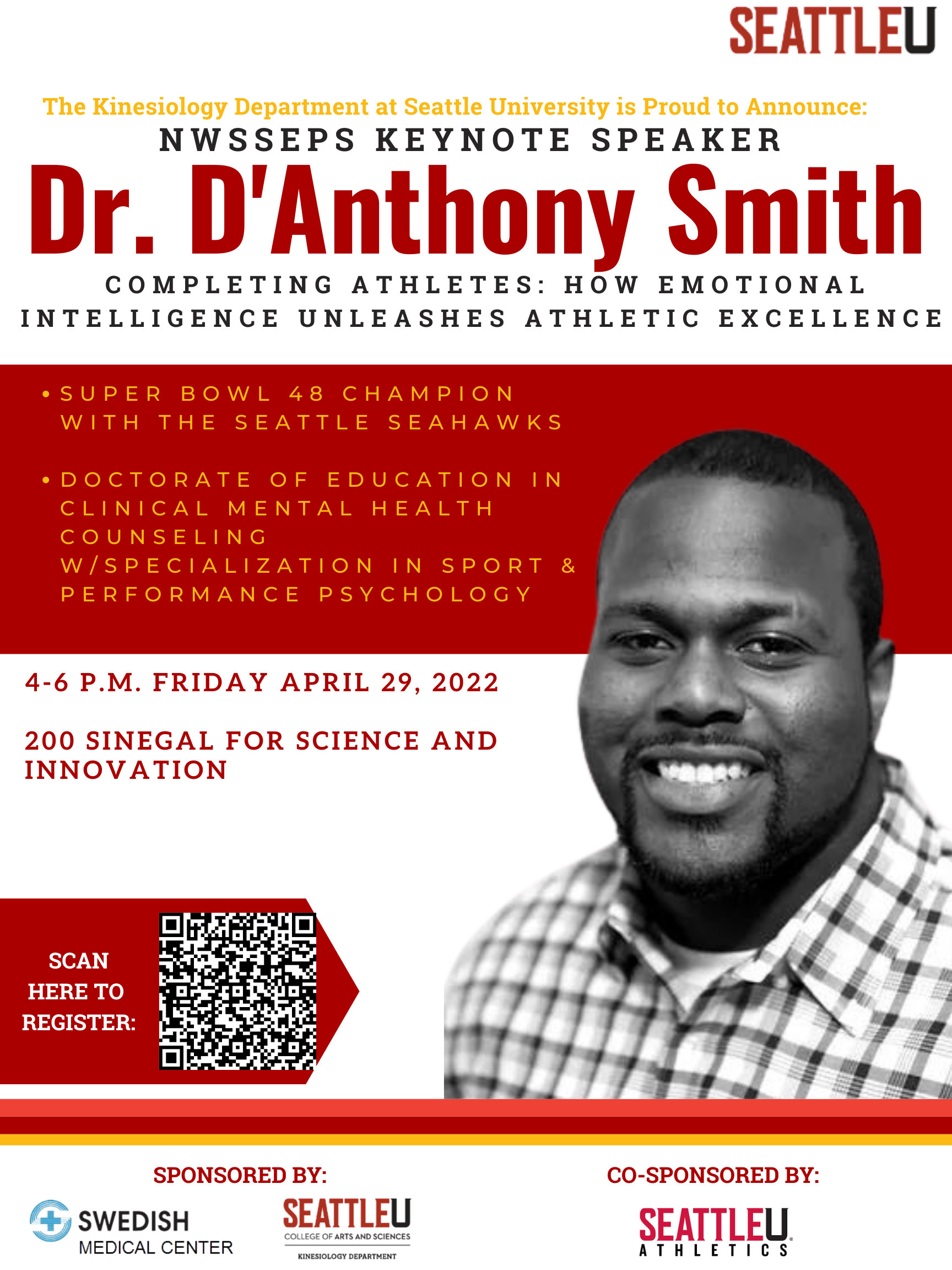

Friday, April 29, 5:30-6:30 p.m.

Friday, April 29, 5:30-6:30 p.m.

Spring Quarter: Wednesdays, April 13–May 25

Spring Quarter: Wednesdays, April 13–May 25.png)

Renew your spirit and vision for life. Give yourself the gift of a weekend retreat based on the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius. Get away to a beautiful retreat center overlooking the shores of Puget Sound for a weekend of rest, personal reflection, group presentations, spiritual direction, and rituals of healing and (optional) Eucharist.

Renew your spirit and vision for life. Give yourself the gift of a weekend retreat based on the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius. Get away to a beautiful retreat center overlooking the shores of Puget Sound for a weekend of rest, personal reflection, group presentations, spiritual direction, and rituals of healing and (optional) Eucharist. When: April, Earth Month

When: April, Earth Month

*Saturday, April 9-Sunday, April 10

*Saturday, April 9-Sunday, April 10

.jpg)

University Recreation is excited to announce its signature event, which takes place Feb. 28-March 6 and features a series of events at Eisiminger Fitness Center and across campus.

University Recreation is excited to announce its signature event, which takes place Feb. 28-March 6 and features a series of events at Eisiminger Fitness Center and across campus.  Thursday, March 10, 12:30–2 p.m.

Thursday, March 10, 12:30–2 p.m.

Thursday, March 17, noon-1:30 p.m.

Thursday, March 17, noon-1:30 p.m.

The International Student Center is hosting its annual

The International Student Center is hosting its annual

The COVID-19 pandemic has made the use of disposable masks a necessity in our daily lives, but that doesn’t mean it’s necessary to send them to the landfill, too! Disposable face masks, like KN95s, N95s and single-use surgical masks, are made of a paper-plastic combination of material that cannot be recycled in a standard blue recycling bin. An estimated

The COVID-19 pandemic has made the use of disposable masks a necessity in our daily lives, but that doesn’t mean it’s necessary to send them to the landfill, too! Disposable face masks, like KN95s, N95s and single-use surgical masks, are made of a paper-plastic combination of material that cannot be recycled in a standard blue recycling bin. An estimated

Allison Greenberg, an adjunct faculty member in the College of Education’s Department of Professional and Continuing Education, is a recipient of the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching (PAEMST).

Allison Greenberg, an adjunct faculty member in the College of Education’s Department of Professional and Continuing Education, is a recipient of the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching (PAEMST).

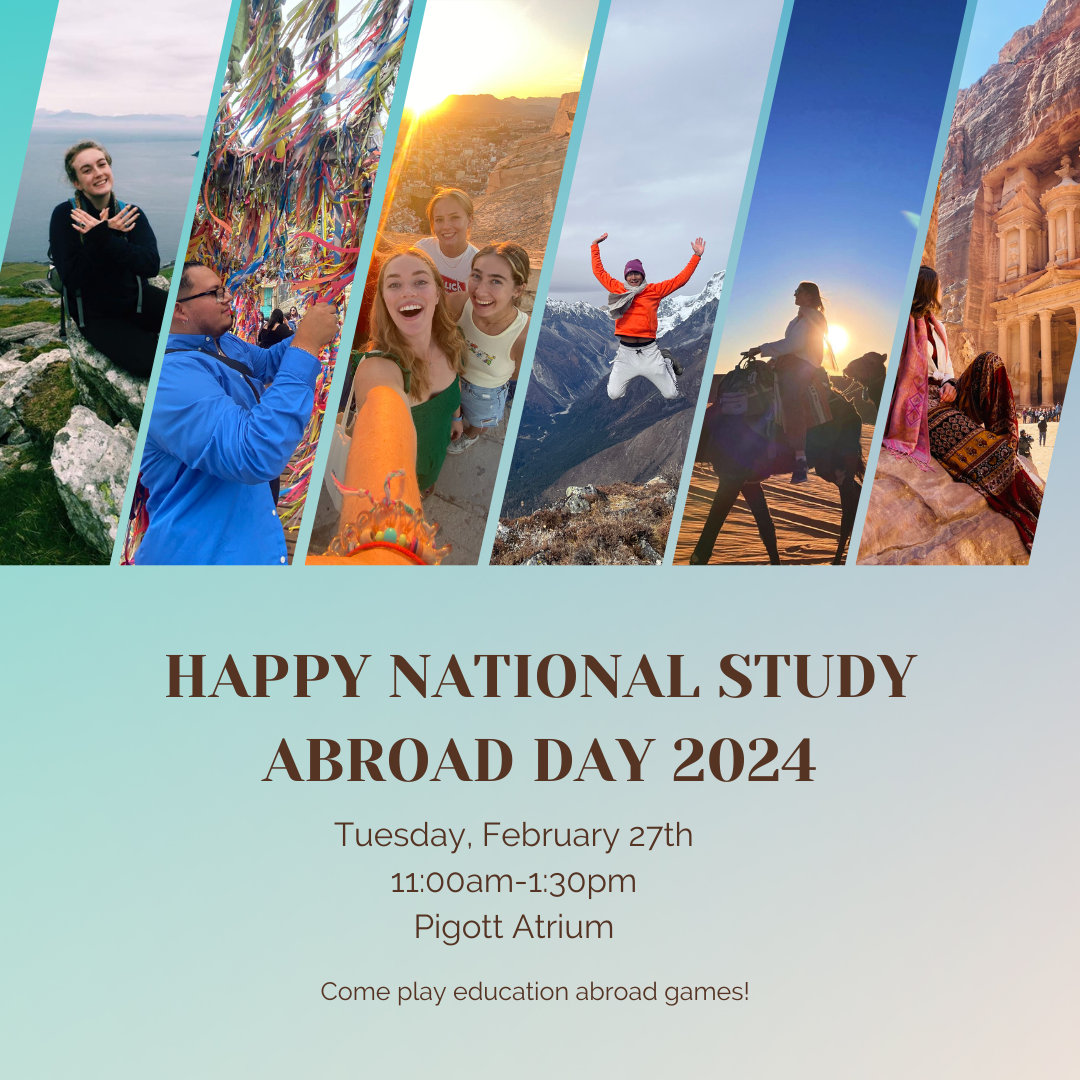

Feb. 28 is National Study Abroad Day and the Education Abroad Office wants to highlight Seattle University faculty's and staff’s international experiences to inspire our students! Share your international education or work experience with us to include on an interactive map, zoom backgrounds, and international education e-mail signature plaques. Let’s celebrate and share our international experiences as we educate future global citizens.

Feb. 28 is National Study Abroad Day and the Education Abroad Office wants to highlight Seattle University faculty's and staff’s international experiences to inspire our students! Share your international education or work experience with us to include on an interactive map, zoom backgrounds, and international education e-mail signature plaques. Let’s celebrate and share our international experiences as we educate future global citizens.

-1130x635.jpg)

James Norris, founder of Ithemba Counseling, will provide his own therapeutic model which has been adapted for use in Seattle Public School educator trainings and for use in therapist trainings throughout the Northwest, California and Arizona. In this interactive event, participants will learn about the model as both a theoretical framework and a practical approach that can help them identify and understand their own experiences.

James Norris, founder of Ithemba Counseling, will provide his own therapeutic model which has been adapted for use in Seattle Public School educator trainings and for use in therapist trainings throughout the Northwest, California and Arizona. In this interactive event, participants will learn about the model as both a theoretical framework and a practical approach that can help them identify and understand their own experiences.

Thursday, Feb. 10 , 12:30-2 p.m., Casey Commons

Thursday, Feb. 10 , 12:30-2 p.m., Casey Commons

Thursday, Feb. 3, 6-7 p.m., Online

Thursday, Feb. 3, 6-7 p.m., Online

Assistant Profesor of Physics Pasha Tabatabai, Ph.D., has been awarded a two-year grant from the National Science Foundation through the competitive “Launching Early-Career Academic Pathways” (LEAPS) program. The funding will enable Tabatabai to significantly advance his foundational work quantifying the rules that govern biological systems. Specifically, Tabatabai’s lab will define and characterize the mechanical properties of non-equilibrium schools of fish, thus allowing a comparison between traditional material science and living materials with the ultimate goal of inspiring new material design.

Assistant Profesor of Physics Pasha Tabatabai, Ph.D., has been awarded a two-year grant from the National Science Foundation through the competitive “Launching Early-Career Academic Pathways” (LEAPS) program. The funding will enable Tabatabai to significantly advance his foundational work quantifying the rules that govern biological systems. Specifically, Tabatabai’s lab will define and characterize the mechanical properties of non-equilibrium schools of fish, thus allowing a comparison between traditional material science and living materials with the ultimate goal of inspiring new material design. NEW TIME! Wednesdays, Jan. 12–Feb. 16 | 12:40-12:55 p.m.

NEW TIME! Wednesdays, Jan. 12–Feb. 16 | 12:40-12:55 p.m. Winter Quarter – Thursdays, Jan. 20, Feb. 3, Feb. 17, March 3 and March 17

Winter Quarter – Thursdays, Jan. 20, Feb. 3, Feb. 17, March 3 and March 17

.png)

The theme of Seattle University’s 2021 Christmas video is “coming together to celebrate joy and inclusion,” and Marketing Communications is looking for participants.

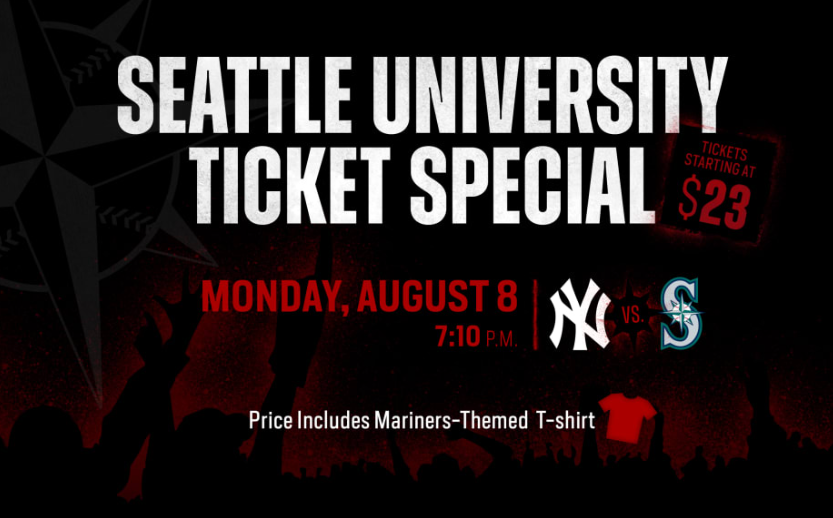

The theme of Seattle University’s 2021 Christmas video is “coming together to celebrate joy and inclusion,” and Marketing Communications is looking for participants. The 2021-22 basketball season is underway and the Redhawks are unbeaten at home thus far. Cheer on the team when they return to action Thursday, Nov. 18 against Morgan State. Tip off is 7 p.m. in the Redhawk Center.

The 2021-22 basketball season is underway and the Redhawks are unbeaten at home thus far. Cheer on the team when they return to action Thursday, Nov. 18 against Morgan State. Tip off is 7 p.m. in the Redhawk Center.

Tuesday, Nov. 23, 1–2 p.m.

Tuesday, Nov. 23, 1–2 p.m.

Gregory Lucey, S.J., who served as Seattle University’s vice president for planning and development in the 1980s, died this morning.

Gregory Lucey, S.J., who served as Seattle University’s vice president for planning and development in the 1980s, died this morning.

Wednesday, Jan. 26, noon This is the second of five workshops, which take place every other Wednesday, noon-1 p.m.

Wednesday, Jan. 26, noon This is the second of five workshops, which take place every other Wednesday, noon-1 p.m.

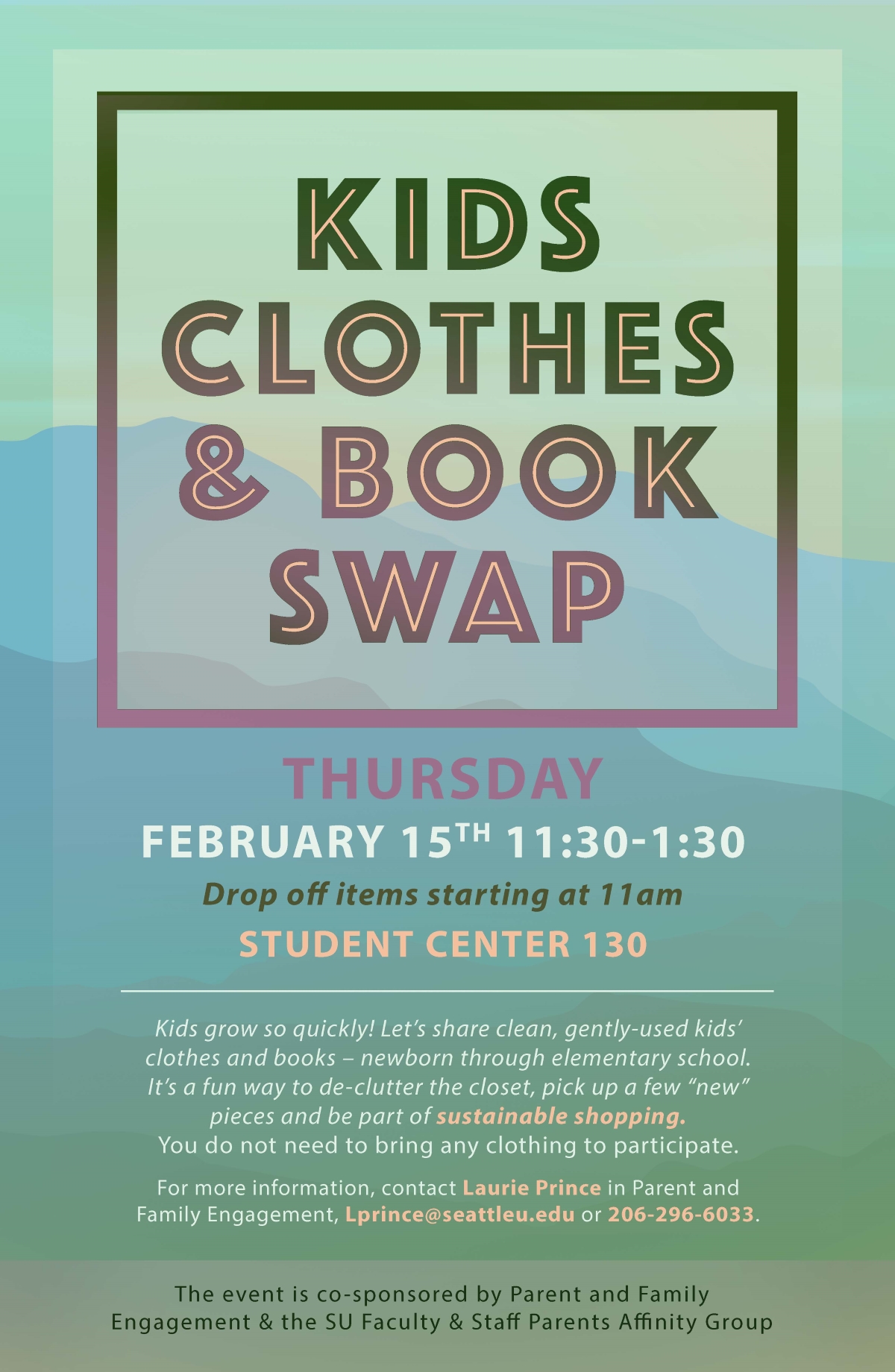

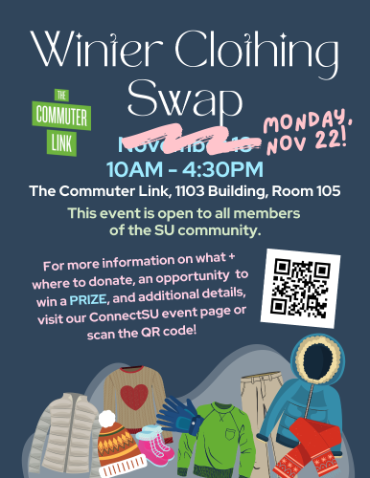

The Commuter Link is hosting a Winter Clothing Swap—similar to its annual Spring Clothing Swap, but for colder weather. Like the annual campus-wide Spring Clothing Swap, the goal is to focus on sustainable ways to upgrade and clean out your wardrobe while bringing the campus community together for a great cause. The event is free and open to all members of the Seattle University community.

The Commuter Link is hosting a Winter Clothing Swap—similar to its annual Spring Clothing Swap, but for colder weather. Like the annual campus-wide Spring Clothing Swap, the goal is to focus on sustainable ways to upgrade and clean out your wardrobe while bringing the campus community together for a great cause. The event is free and open to all members of the Seattle University community.